James Doig is the Senior Digital Archivist at the National Archives of Australia.

This is a tale that carries a key digital preservation message: recovering the bits from obsolete carriers and ensuring those bits are properly cared for when it is still possible to do so will lead to positive outcomes that may not be fully realised for years into the future.

Our story begins way back in the early 2000s, a time when what are now universally agreed digital preservation principles and workflows were still being developed, and before familiar standards like PREMIS and OAIS were available. In 2003 the National Archives of Australia commenced a project to audit obsolete carriers in its collection and to recover the data from those carriers. The dates of the carriers ranged from 1970 up to the late-1990s. The audit identified 300 carriers, categorised as follows:

|

Carrier Type

|

3½” Macintosh Floppy Disks |

Burroughs B20 5 ¼” Floppy Disks |

Wang 8” Floppy Disks (Wang DOS) |

Wang 8” Floppy Disks (Wang OIS) |

9-Track ½” Magnetic Tapes |

|

Number

|

60 |

32 |

22 |

49 |

137 |

Following the audit, we sought the aid of data recovery specialists, and worked closely with them not only to recover the data but also to fully document the recovery process. A detailed process for data recovery was developed that included the capture of a full audit trail of steps in the data recovery process to ensure fixity, provenance, authenticity and the chain-of custody for archival management. The data recovery project was classified into a four-stage process: step 1 – obtain bit-level disk images of all of the content on each physical carrier; step 2 – extract individual bit files from each of the physical carriers; step 3 – analyse and identify duplicate files and proprietary or complex formats; and step 4 – document the results for future archival reference and preservation processes.

The recovery process was surprisingly successful. Of the 300 carriers treated, 257 (86%) achieved 100% reads in phase 1 (i.e. disk images were obtained) and 245 (82%) achieved 100% reads in phase 2 (i.e. complete digital object recovery). Partial recovery of bit files was achieved in about 5% of cases.

Obtaining useable copies of the bit files, for example by using rendering or interpretation software, proved more problematic. Following some testing using InterMedia, a media and data conversion system available at the time, and text editors, the project was wound up without producing copies of the data that could be rendered for access using contemporary software. Nevertheless, the disk images, bit files and process documentation where carefully stored and preserved, in the expectation that the project could be picked up and completed in the future.

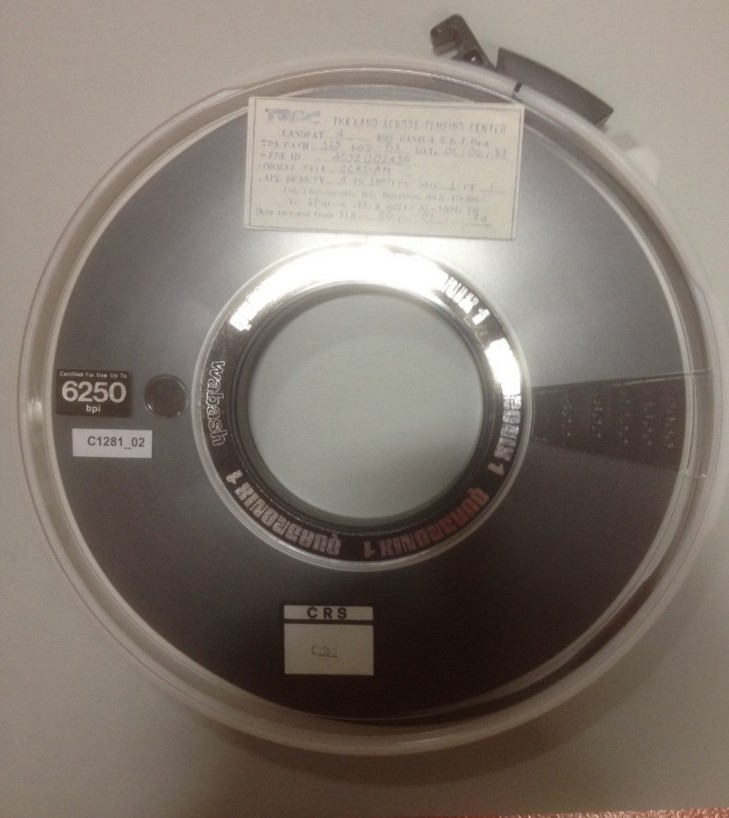

In early 2020 the National Archives revisited data recovered from two 9-Track ½” magnetic tapes, which the label on the carrier suggested were Landsat satellite images of Vietnam.

One of the 9-Track ½” Magnetic Tape which stored the original Landsat data.

In the early 2000s, the data recovery company was unable to make sense of the recovered bit files -they were in a proprietary format and could not be accessed. Hex editors could extract little information about the native format:

The bit sequence from one of the Landsat files rendered via a hex editor in 2020

In 2020 we decided to use a widely-used image analysis software, ENVI, to see if it could render the content. While not perfect, the images were recoverable and were able to be exported as high resolution TIF files which can be preserved and accessed:

Rendered TIFF file in 2020

Future work on the recovered disk images and/or bit files could focus on emulation techniques to reconstruct the performance of the digital records when they were in active use. The ‘belts-and-braces’ approach adopted in this early data recovery project – obtaining disk images, bit files, and a thorough description of process – and securely preserving the resulting bitstreams, can ensure future access.

Comments