The DPC’s ‘big data siren’ went off again last month when no less an authority than The Economist proclaimed, ‘The World’s Most Valuable Commodity is no Longer Oil But Data’. Normally a mournful foghorn warning business away from things it cannot (or will not) understand, The Economist has been quite the advocate for the digital economy over the years. But whatever your view on the ‘big data bubble’ there is little doubt about the place data occupies in the long history of the economy: indeed Jack Goody, Michael Clanchy and others would have you believe that control over resources was the principal reason for the invention of literacy in the first place and thus indirectly of data too. You might well conclude that The Economist is sounding a millennia-old headline, ‘how can emergent forms of literacy expand new economic activities’.

DPC maintains a ‘big data siren’ because the commentariat, left or right, seem seldom to consider what data is and whether it’s sustainable. It’s a significant weakness. To the right: if we build an economy on data, are we not building on sand? To the left: can something as fragile as data really induce the end of capitalism? What happens if we place digital preservation into that narrative?

(I should warn you this is a long one. Go to the toilet before we start; find a comfy chair; pour yourself a glass of something. I write as a friend thinking out loud and if I provoke you to agree, disagree or form a better alternative, then the time we share will be time well spent.)

History Ended

I don’t really know where to start a discussion on the role of data in the economy, so will start with my own shallow experience which curiously enough coincides with the end of history. November 1989 to be exact. With epochal precision, the fall of the Berlin Wall coincided with the month that my undergraduate history course was scheduled to meander through its compulsory, worthy-but-dull-review of modern Germany. The programme, rendered increasingly obsolete with every news bulletin, was abandoned for a couple of weeks. Instead we had the sudden luxury of expert witness and explanatory context to the events around us. History (ie the syllabus) was suspended: the classes became free-wheeling debates on the roots of the tumult and scrupulously informed analyses on its consequences. The lecturers, who seemed to be enjoying their profession, practised on us in the daytime so they could be pitch-perfect for the late-night news shows, interpreting past positions for future possibilities. You might call it the end of history. It was at least an intermission.

But the ‘end of history’ is not my phrase. It’s how Francis Fukuyama described the much of the early 1990s, not so much the end of the world as the culmination of human endeavour, the perfect balance and ultimate fulfilment of history’s struggles:

‘What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind's ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.’

It was an enticing contention in the years that saw capitalism triumph over communism, democracy over totalitarianism and humanity over apartheid. Europe’s megalithic states crumbled East and West while its principle trading bloc became an economic and social then monetary union. The arms race was over and peaceful co-existence could begin at last, not least in the blighted Cold War client states where dictators looked suddenly vulnerable. Political certainties were thrown out: conservatives became radicals; nationalists became internationalists; and socialists became social democrats. Rational materialism prevailed, unencumbered by archaic pieties of equality, modesty or faith. Greed was suddenly proven good. Auto-erotic cults of individualism cloaked avarice as aspiration. The scope of government narrowed, its ancient promises abrogated, the shelter it offered to the most vulnerable was abruptly removed. The only elements of the state that expanded were those enforcement agencies that protected enterprise or prosecuted its detractors. The logic, values and institutions of the market deluded many, overwhelmed most and permeated all. Self-regulating, self-correcting and liberated of political (one may say democratic) interference, the market replaced failed ideologies as the epitome and motor of human creativity. In this new era, happiness equated to prosperity, ambition supplanted hope, and the truest route to prosperity became individuals pursuing their own self-interest. Society was pronounced dead.

That was the idea. It didn’t quite work out like that.

We didn’t know that a single currency could also destabilise a continent; that open borders within Europe might strangely alienate Europeans from each other and create such havoc at its margins. (Western governments used to complain about an Iron Curtain imposed by diktat upon the struggling masses that wanted to be free: look now how we are erecting new ones in our own image). Deregulation of banking seemed like a good idea, as did the wholesale transfer of vital, even profitable, national infrastructure to the private sector. Trickle-down-theory was a thing. Who could have predicted that the gentle advance of political correctness could become a trap of demagoguery? Who could have anticipated new religious radicalization, and for that matter the new anti-religious fundamentalisms? We didn’t know about suicide bombers, collateralised debt obligations or the bifurcation of globalization. In these simpler times, the dot.com bubble was still just soapy liquid; Tony Blair’s dodgy dossier was still just wood pulp; and Titanic won eleven Oscars. I can’t really propose anything better but it’s hard to argue that the decade of BritPop, Friends and Sonic the Hedgehog was the zenith of human achievement.

Uninventing Obsolescence

This is a digital preservation blog and a digital preservation theme is going to emerge sooner or later. Bear in mind that the 1980s and especially the early 1990s also saw the exponential rise of home computing and the Internet. This was the decade that, without which, the digital estate would have taken a radically different direction (if it existed at all). The economic forces that shaped the 1980s and 1990s created the norms of the digital universe we occupy today and thus, digital preservation. One might suggest that, had these economic processes been less consumerist, less disposable, more resilient, and more sustainable, then the endemic challenges of technical obsolescence, resource discovery and short-termism which we address in our daily work would not have arisen in the way that they subsequently have. By some strange process that I cannot fully delineate, digital preservation is permanently cleaning up after the neo-liberal economics of the 1990s. If you will permit a wild collision of clichés: the End of History created the Digital Dark Age.

If the End of History was a myth for the 1990s so the Digital Dark Age was a myth for the 2000s, partly because some of the claims were over-blown and mostly because a mix of sheer frustration, judicious insight and painstaking effort has ensured that individuals, then groups began to work the problem. (Pause for a moment to celebrate those gifted and insightful ones among us.) As early as 2006 commentators (such as Chris Rusbridge) were starting to hint that the problems were more complicated and the solutions more subtle than the shock headlines might accommodate.

For the record, I don’t think digital preservation is fixed; I don’t doubt that individuals, organizations and perhaps entire sectors run significant risks of data loss and that there will be a series of ‘black hole’ incidents. Similarly, I don’t doubt that obsolescence, resource description and operator error are authentic and immediate threats which need prompt and concerted effort. But my sense of the challenges of digital preservation has changed over time. I am more worried now by corporate abandonment, malicious deletion and ill-managed encryption as long-term threats to our digital memory than I was before. I recoil from the duplicitous erosions, obfuscations and eliminations of the rich and powerful who seek to sanitise or erase uncomfortable narratives. I have learned that relevance ranking can be more revealing than data. But the brute force of obsolescence, whether of media, file formats or data is no longer inevitable: and being avoidable it can only coincide with some form of negligence. It’s not like we’ve not tried to tell anyone about this, all the while helping a large and growing community to assemble useful solutions. That also means we can situate digital preservation quite differently within the narrative of this elementary economic history: because obsolescence is not some irresistible, invisible force.

I suppose contemporary economic analysis starts on the 15th September 2008 (you say 09/15/08; I say 15/09/08: but a couple of digits in the wrong column never harmed anyone) being the day that the long boom went bust. The humiliation of Lehman Brothers has generated a huge amount of commentary but I’d like to propose three digital preservation perspectives to consider.

At an elementary level, we should at least ask what happened to the corporate (digital) records. Not only could these provide a telling insight into what went wrong and who was to blame but analysis of this data presumably has a role to play in the entire next five centuries of economic history. I recall that the insolvency practice of PricewaterhouseCoopers liquidated the UK investment arm and might have interesting if highly confidential views on the data and where it ended up. Considering that Lehman Brothers struggled even to sell its billion-dollar Manhattan office block I cannot imagine there would have been much money left to pay for the maintenance of the company records. Maybe some reader would be kind enough to enlighten us.

But there are two aspects demand our attention and provoke us to action: one is inward looking about the assumptions and emergence of digital preservation as a practical effort; and the other is more outward looking about the role of information technology and digital preservation in what some now call late-capitalism.

Victims of History

By September 2008 it had become apparent that we were living in turbulent times. If digital preservation came of age in the late 1990s and early 2000s, then we grew up with a set of assumptions that challenge us to think a bit more carefully about our place in history. My as-yet-unsubstantiated analysis begins with a realisation that the early days of digital preservation coincided with a period of economic boom which everyone said was the new historical normal. Digital preservation was born in a long super-cycle, so long and so super that talented economists congratulated themselves on engineering an end to boom-and bust. They were wrong.

Digital preservation has not been immune from the ensuing mayhem. I normally grumble about how hard it is to convince agencies to invest in data, but it takes some nerve to ask for investment in something as exotic as data. Did we not all see the tide of cupidity, miss-selling and downright fraud which swept much of the public sector to bankruptcy? And, when houses are not as safe as houses, I am inviting an investment in what?

I hope you will forgive this flippancy as a rhetorical device, because it’s not a joke. Consider for example the widespread recruitment freeze and redundancy rounds that followed the banking crisis. Instead of hiring new starts with keen new digital skills, within about 18 months employers in the public and private sectors started shedding many (globally thousands) of archivists, conservators and librarians. The normal employment cycle stalled so, instead of recruiting from masters’ programmes, the incoming generation of digital archivists were in many cases re-deployed from the global redundancy pool. Tech-savvy-developer-kids need not apply. Perversely, masters’ programmes in digital preservation and curation have struggled at exactly the time these skills have been most needed, a weird and unforeseeable consequence of austerity.

Setting aside the morale crisis and freeze on wages, this pretty much blew any chance of a new ‘digital preservation’ profession emerging as had been suggested a few years earlier. Existing professional channels were reinforced instead. Digital preservation roles were inadvertently cast as non-technical by agencies who didn’t really understand the topic but were desperate to retain loyal staff to whom they owed a hearing. Salaries were fixed at levels congruent with library and archive posts, which further inhibited the recruitment or retention of in-demand developer skills.

And it’s not simply a matter of staffing and skills. There’s something in this too about expectations and configurations of digital preservation tools and standards. Looking back, expectations of good practice in 2005 seem outlandish in comparison to what we might try to achieve now. There’s a reason why contemporary buzzwords in digital preservation emphasize ‘minimal effort ingest’ or ‘parsimonious preservation’. Our problems are not simply about data volumes and work flows but self-evidently about money too, which as David Rosenthal elegantly reminds us ‘turns out to be the major problem facing our digital heritage’. Working at scale means ‘doing more with less’ which in our decade of austerity might as well be stamped on the bottom of every invoice, budget plan and pay slip. Digital preservation is no more immune to economics than the Masters of the Universe on Wall Street.

In my next blog post I want to develop that slightly more with some reflections on our values: but that’s a long detour. Let’s keep on the economics for now.

Late Capitalism

If the End of History was a narrative of the 1990s and the Digital Dark Age a theme of the 2000s, then perhaps ‘Late Capitalism’ is a fitting tag for the 2010s. It has been argued that the collapse of Lehman Brothers – a company valued over 600bn USD - was not the cause of a crisis but the symptom of a deeper malevolence: not a corporate failure but a systemic one: Digging into the causes of the failure, Paul Mason argues that‘Capitalism’s failure to revive has moved concerns away from the scenario of a ten-year stagnation caused by overhanging debts towards one where the system never regains its dynamism. Ever.’

He identifies four key trends that brought Lehman Brothers down. His simple contention is that if these trends persist then the root is not poor corporate governance but structural dysfunction that is beyond repair. The results he terms the End of Capitalism and, like generations of lefty thinkers, he argues the end of capitalism is imminent. Three of these underlying forces – fiat money, financialization and global imbalances – are way out of scope for this blog and my capacity to comment. But his fourth theme, the impact of information technology and the way it remakes value, is a light to this particular moth.

On the Road to Wherever

Debate about the role of technology in capitalism’s response to the financial crisis lead us neatly back to the big data headlines with which we started.

Although there are widely varying views on where our data driven economy might be taking us – if you have time compare Paul Mason’s analysis to Viktor Mayer-Schönberger; if you don’t have time then just enjoy Irvine Welsh’s rage – there is broad consensus on the characteristics of data that set us on the road to wherever. Data is evidently abundant, it is valuable, it is frictionless, it is inexhaustible, and the real transformation comes from incremental additions of heterogeneous and distributed technologies. This is where I start to part company from the mainstream assessments of the new economy. Challenging this naivety and cultivating a deeper understanding of the fragility of data is one of the spaces where I think the digital preservation community has a right – in fact a pressing need – to intervene cogently and compellingly in public discourse.

There’s little debate that data is indeed abundant. If anything it’s a little too abundant. But the implication that abundant opportunities flow from super-abundant data cannot be taken for granted. On one hand, the abundance itself becomes a challenge. I am fond of repeating a comment of my friend Paul Miller at a DPC briefing day a few years ago to the effect that finding useful data, formerly like finding a needle in a haystack, is now like finding a needle in Germany. So, like oil, data needs an expensive production line turning crude raw materials into something useful. This infrastructure has to exist first if the abundant opportunities are to be exploited, and – at least in the UK – we’re a long way from having anything like the skilled workforce needed to build and operate those processes.

While we might be amazed at the abundance of data just now, that’s not necessarily a guarantee that the trend will continue indefinitely. This takes me back (as usual) to David Rosenthal’s prescient analyses of storage costs. We’ve enjoyed 50 or more years of consistent, predictable improvements to media and chip technology, and therefore a 50-year bonanza in storage capacity and processing power. But that needn’t go on forever: sooner or later fundamental laws of physics and practical realities of engineering will intervene. So, as with the financial super-cycle, we can’t assume growth to be the historic norm.

There’s also an assumption that data is ‘frictionless’. The implication is that data can be transported and transplanted around the world at almost no cost, reducing intermediation (the decline of the High Street and the Library are outcomes of the same process) and placing producers and consumers in direct exchange. Because digital is a universal platform the effects are profound; because digital is a globalised phenomenon jurisdiction fails; and hence the normal rules of trade, and many sources of revenue and employment are heading towards obsolescence.

The supposed frictionless state of data is point and counterpoint to how the left and the right view the emerging economy. On the right, frictionless-ness is the last talisman of free trade, making an instant absurdity of any effort to regulate or restrain market forces: if the government doesn’t like what you’re selling or how you’re selling it then you can move wherever the rules suit; and if you don’t like your supplier then you’re only one click away from a new one. You can even will your own currency into existence. On the left, frictionless-ness is the last acme of capitalist folly, the easy exchange of data undermining traditional concepts of property. And having made all transactions ultimately about information which cannot be confidently valued, capitalism has inadvertently deleted the concept of the market.

There are substantial flaws with both arguments, which others will point out more effectively: I am straying well out of my comfort zone. But even from here I can see that the Internet and its service providers don’t replace intermediation but have become intermediaries; that libraries and archives are also about selection, authenticity and memory; that trade has always negotiated jurisdiction.

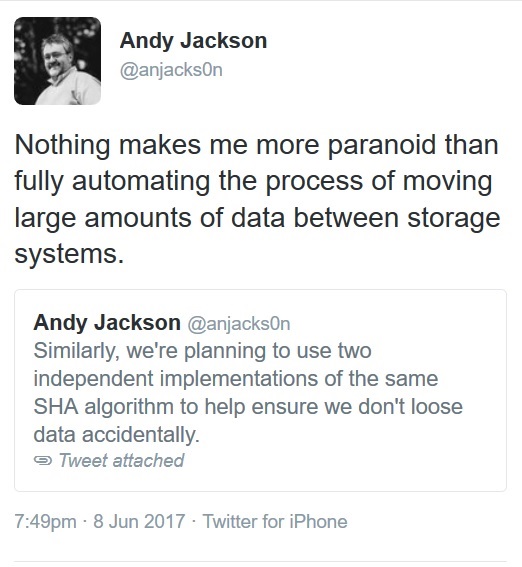

But there’s a digital preservation angle here too. Data just doesn’t seem frictionless to me: on the contrary, it can be very hard work. It might be fashionable to bring Julian Assange, Edward Snowden or Alexandra Elbakyan into the discussion and for sure the headlines are full of examples of contentious data loss or theft. But that diverts to a different controversy. Instead, ask any web archivist if data is frictionless: or a repository manager trying to look after research data; or a records manager trying to pioneer a corporate EDRMS. For me there was a tipping point at ADS when the task of persuading people to deposit data got overtaken by the job of looking after it: we had to go easy on the collections development and concentrate on ingest. And that’s not just my experience. Something as benign and important as the UK Web Archive does not come about by magic. I respect the work of Andy Jackson and colleagues hugely: but not because it is easy but because it is incredibly hard and they are impressively skilled. That’s to say you don’t need to be James Bond villain to find friction in data: even in well-founded institutions acting openly in the public interest and with a benign legislative environment and committed leadership, data is hard work.

But there’s a digital preservation angle here too. Data just doesn’t seem frictionless to me: on the contrary, it can be very hard work. It might be fashionable to bring Julian Assange, Edward Snowden or Alexandra Elbakyan into the discussion and for sure the headlines are full of examples of contentious data loss or theft. But that diverts to a different controversy. Instead, ask any web archivist if data is frictionless: or a repository manager trying to look after research data; or a records manager trying to pioneer a corporate EDRMS. For me there was a tipping point at ADS when the task of persuading people to deposit data got overtaken by the job of looking after it: we had to go easy on the collections development and concentrate on ingest. And that’s not just my experience. Something as benign and important as the UK Web Archive does not come about by magic. I respect the work of Andy Jackson and colleagues hugely: but not because it is easy but because it is incredibly hard and they are impressively skilled. That’s to say you don’t need to be James Bond villain to find friction in data: even in well-founded institutions acting openly in the public interest and with a benign legislative environment and committed leadership, data is hard work.

I can well imagine how, from the gilded bureaux of the commentariat this could be misunderstood, but that’s not the experience on Raasay or really anywhere that’s waiting for telecomms supplier to upgrade the broadband. (Gratuitous photo of the view to Skye from Raasay supplied. If the broadband were better I would simply move here and camp out permanently on the DPC Webex account.) Politicians understand digital infrastructure as fibre and little else. I tried to explain metadata to a business minster once. (She gave me ten minutes but left half way through to get her photo taken). If data is frictionless, it’s only because lots of people have put in lots of hours in to make it that way.

I can well imagine how, from the gilded bureaux of the commentariat this could be misunderstood, but that’s not the experience on Raasay or really anywhere that’s waiting for telecomms supplier to upgrade the broadband. (Gratuitous photo of the view to Skye from Raasay supplied. If the broadband were better I would simply move here and camp out permanently on the DPC Webex account.) Politicians understand digital infrastructure as fibre and little else. I tried to explain metadata to a business minster once. (She gave me ten minutes but left half way through to get her photo taken). If data is frictionless, it’s only because lots of people have put in lots of hours in to make it that way.

It seems uniformly accepted that data is valuable, but no one yet seems to have worked out a way to put data on a balance sheet. Accountancy still relegates data to the hinterlands of ‘intangible assets’. But there’s something going on, as a simple analysis of stock market trends demonstrates. Shares in Facebook, for example, were first sold to the public on 11th March 2012. At that time, the company had fixed assets and cash of 6.3bn USD but the share valuation was 104bn USD, meaning the company had intangible assets values at almost 100BN USD. It invites a naïve calculation: if you subtract the value of the tangible assets from the value of the company you get the net value of the data. If the 2.1 trillion pieces of data that they held were indeed valued by the market at 97.7bn USD, then each individual data point would be worth about 5US cents.

There are probably three things to discuss here. Firstly, if data like this were stock in the old-fashioned sense then this an incredible feat since the cost of production to Facebook has been almost nil. Secondly, arguably it adds nothing to the economy and quite possibly is a cost to the productive capacity of every other company in the world, since time spent on social media is time not doing other higher value activities. Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, I don’t think anyone actually thinks about data as a static product. The value lies in re-use potential, and from this qualification a digital preservation theme becomes apparent. Because if you don’t preserve it you can’t re-use it. It's become fashionable to talk of data 'going dark'. To extend the metaphor, digital preservation offers perpetual daylight.

The ‘data is the new oil’ mantra is a strange juxtaposition. Oil is fundamentally a natural resource which is used once and cannot be used again: it is non-renewable and rivalrous. As they say in the supermarkets: ‘when it’s gone it’s gone’. Data on the other hand is a very unnatural resource. It can be used over and over in the right circumstances. A few years ago, the Blue Ribbon Task Force described this as ‘non-rivalrous consumption’, noting that this consumption is path-dependent (so what you do now is constrained by decisions made before now) and temporally dynamic (consumption can last a long time but is liable to change through that time).

It has become fashionable to suppose that data is in some way inexhaustible. But the experience of the digital preservation community shows that this assumption is misleading. To be precise, data is only inexhaustible insofar as it is path independent. So data which is not preserved will effectively be lost to re-use, while the utility of preserved data may be inadvertently (perhaps even consciously) constrained by preservation actions, designed with respect to the needs of a designated community. And if data re-use is path dependent, then there is at least one major fork in the road which we might as well call the high-road and the low-road: unmanaged erosion through abandonment, or strategically-designed enduring utility. Neither warrant the conclusion that data is inexhaustible. Thus, another digital preservation theme emerges in opposition to received wisdom. It also invites a closer consideration of dependencies now and dependencies in the future.

A final theme associated, not simply with big data but with much technological speculation is that the emerging economic trend is additive and distributed. We talk more about innovation than discovery these days. Penicillin was a discovery of great importance: driverless cars are not. That doesn’t mean they won’t be transformative, it’s just that they are mostly a design challenge of putting a variety of well-known technologies together. This kind of innovation invites interdependency, and interdependency amplifies preservation risks.

There’s a whole other blog post here about why I struggle with data as a concept, but for now let me sketch out how interdependencies between data and applications are a preservation risk. The more we move to Cloud storage and processing, the more we benefit from the economies of scale, especially but not only with respect to elasticity of storage and processing. We’re also moving to utility – on demand – computing which means data and tools are rented not acquired. What’s not always obvious is that these services depend on other services and so on pretty much ad infinitum. So software is maintained through small, frequent changes rather than canonical releases.

That’s good for all sorts of reasons, but note that the dependencies and updates may never be apparent, except when they are glaringly and calamitously so. For pure whimsy you can’t do better than when Google updated a font set in January 2016 and the letter ‘f’ disappeared for a few hours. I will leave you to work out the implications, cute and otherwise, and imagine what that might mean for preserving, presenting and maintaining an authentic record.

History Needs Us and the Future Even More So

We’ve travelled quite a distance in this post so I owe you a conclusion. As always I welcome your corrections and refinements. I offer you three observations.

Firstly, obsolescence and digital preservation are historically constituted products of different and complicated processes. We could do worse than to situate ourselves in the historical moment. Obsolescence is neither spontaneous nor inevitable but in some small way a choice that the markets made for us in the 1990s, or more accurately a choice that we all made as actors in those market places (with thanks to Peter Webster for the precision). Digital preservation, our response to obsolescence, came of age just as an economic long-super-cycle came to a staggering halt. Therefore, we sometimes pack assumptions about resources and outcomes which may have been reasonable in the early 2000’s but seem strangely maladjusted to our times. We have to get used to the idea of doing more with less, not just because of the vectors of data growth, but the harsh realities of our economies.

Secondly, there are competing narratives from left and right about the economy based on presumed characteristics of data - frictionless, abundant, additive, valuable, inexhaustible – which I don’t fully recognise. Digital preservation challenges these properties and by extension challenges also the economics that assume them. To the right: if it is our intention to build an economy out of data, doesn’t the experience of DPC members suggest we are building on sand? To the left: if data really will provoke the end of capitalism, won’t the capitalist processes apparently driving innovation towards its own redundancy not simultaneously yield the obsolescence that saves it? Neither left nor right have fully appreciated the fragility of data. It's not my role to offer a corrective here on what that might mean for these prognostications. But there is a role, indeed a pressing need, for our experience of digital preservation to inform and revise those analyses.

Finally, the value of data is in reuse. Unless we figure out how to secure this data for access and re-use in the long term we simply cannot derive long term value from it. (I know that value has many different forms, for the purposes of this post I am choosing to concentrate on economic value). That would be an economic failure of generational proportions. It’s not one we can afford to postpone. Our thriving digital preservation community means ignorance is a poor excuse and is no longer a credible response. Obsolescence is optional, and being a choice exists only in contexts of negligence, failure or recklessness. Data seems the one shared hope for the economic future whether your vision is from the left or right so failure to act on obsolescence is to put at risk the one flickering light in a gloom that has barely lifted since 2008.

I started with a frivolous remark about the ‘big data siren’, but it’s too serious for flippancy. There’s an urgent economic necessity in this. It’s time we were clearer: agencies that invest in the development of data but don’t have policies regarding the long-term value and exploitation of these data sets are derelict in their duty to themselves and to the future. We have an obligation to call them out.

The consequence will not be a digital dark age. It’s a plain, old-fashioned dark age.

I am grateful to Neil Grindley, Mairi-Claire Kilbride, Sarah Middleton, Dave Thomson, Peter Webster and Jane Winters who commented on elements of this post prior to release.