Handbook

Technical solutions and tools

Illustration by Jørgen Stamp digitalbevaring.dk CC BY 2.5 Denmark

Who is it for?

Operational managers (DigCurV Manager Lens) and staff (DigCurV Practitioner Lens) in repositories, publishers and other data creators, third party service providers.

Assumed level of knowledge

Novice to Intermediate.

Purpose

- To focus on technical tools and applications that support digital preservation: software, applications, programs and technical services.

- To consider the practical deployment of preservation techniques and technologies whether as relatively small and discrete programs (like DROID) or enterprise wide solutions that integrate many tools.

- This section excludes other more strategic or policy issues and standards that are sometimes described as tools: these are covered elsewhere in the Handbook.

Metadata and documentation

Illustration by Jørgen Stamp digitalbevaring.dk CC BY 2.5 Denmark

Introduction

This section provides a brief novice to intermediate level overview of metadata and documentation, with a focus on the PREMIS digital preservation metadata standard. It draws on the 2nd edition of the DPC Technology Watch Report on Preservation Metadata. The report itself discussies a wider range of issues and practice in greater depth with extensive further reading and advice (Gartner and Lavoie, 2013). It is recommended to readers who need a more advanced level briefing.

Metadata is data about a digital resource that is stored in a structured form suitable for machine processing. It serves many purposes in long-term preservation, providing a record of activities that have been performed upon the digital material and a basis on which future decisions on preservation activities can be made in the future, as well as supporting discovery and use. The information contained within a metadata record often encompasses a range of topics. There is no clear line between what is preservation metadata and what is not, but ultimately the purpose of preservation metadata is to support the goals of long-term digital preservation, which are to maintain the availability, identity, persistence, renderability, understandability, and authenticity of digital objects over long periods of time.

Documentation is the information (such as software manuals, survey designs, and user guides) provided by a creator and the repository that supplements the metadata and provides enough information to enable the resource's use by others. It is often the only material providing insight into how a digital resource was created, manipulated, managed and used by its creator and it is often the key to others to make informed use of the resource.

There are a number of factors which make metadata and documentation particularly critical for the continued viability of digital materials and they relate to fundamental differences between traditional and digital resources:

- Technology. Digital resources are dependent on hardware and software to render them intelligible. Technical requirements need to be recorded so that decisions on appropriate preservation and access strategies may be made.

- Change. While traditional materials may be preserved by predominantly passive preventive preservation programmes, digital materials will be subject to repeated actions, and there will be many different operators and quite possibly different institutions influencing the management of digital materials over a prolonged period of time. Recording actions taken on a resource and changes occurring as a result will provide a key to future managers and users of the resource.

- Authenticity. Metadata and documentation may be the major, if not the only, means of reliably establishing the authenticity of material following changes.

- Rights management. While traditional resources may or may not be copied as part of their preservation programme, digital resources must be copied if they are to remain accessible. Managers need to know that they have the right to copy for the purposes of preservation, what (if any) technologies have been used to control rights management and what (if any) implications there are for controlling access.

- Future re-use. It may not be possible for others to use the material without adequate documentation.

- Cost. It is expensive to create metadata manually and preservation metadata may not always be easily generated automatically. Additional metadata for digital preservation needs therefore requires careful cost/benefit trade-offs.

The PREMIS (PREservation Metadata: Implementation Strategies) Standard

PREMIS (PREservation Metadata: Implementation Strategies) is the international standard for metadata to support the preservation of digital objects and ensure their long-term usability. Developed by an international team, PREMIS is implemented in digital preservation projects around the world, and support for PREMIS is incorporated into a number of commercial and open-source digital preservation tools and systems.

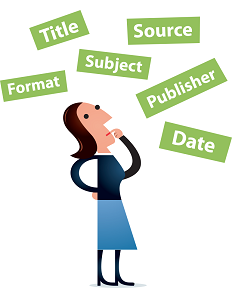

The PREMIS Data Dictionary (PREMIS, 2013) is organized around a data model consisting of five entities associated with the digital preservation process:

- Intellectual Entity - a coherent set of content that is described as a unit: e.g., a book

- Object - a discrete unit of information in digital form, e.g., a PDF file

- Event - a preservation action, e.g., ingest of the PDF file into the repository

- Agent - a person, organization, or software program associated with an Event, e.g., the publisher of a PDF file

- Rights - one or more permissions pertaining to an Object, e.g., permission to make copies of the PDF file for preservation purposes

Taken together, the semantic units defined in the PREMIS Data Dictionary represent the 'core' information needed to support digital preservation activities in most repository contexts. However, the concept of 'core' in regard to PREMIS is loosely defined: not all of the semantic units are considered mandatory in all situations, and some are optional in all situations. The Data Dictionary attempts to strike a balance between recognizing that there will be a significant overlap of metadata requirements across different repository contexts, while at the same time acknowledging that all contexts are different in some way, and therefore their respective metadata requirements will rarely be exactly the same.

Implementation

Although the PREMIS Data Dictionary is not a formal standard, in the sense of being managed by a recognized standards agency, it has achieved the status of the accepted standard for preservation metadata in the digital preservation community. A strength but also a limitation of the PREMIS Data Dictionary is that it must be tailored to meet the requirements of the specific context; it is not an off-the-shelf solution in the sense that an archive simply implements the Data Dictionary wholesale. Only a portion may be relevant in some digital preservation circumstances; alternatively, the repository may find that additional information beyond what is defined in the Dictionary is needed to support their requirements. For example, the Data Dictionary makes no provisions for documenting information about a repository's business/policy dependencies, which may be needed to support preservation decision-making.

In short, each repository will need to invest some effort to adapt preservation metadata and documentation standards to its particular circumstances and requirements.

During implementation an institution normally identifies its own minimum standard of information required for catalogued items in the collection. Each institution can also identify its preferred levels of metadata and documentation for acquisitions and may notify and encourage suppliers or depositors to supply this information. Staff review and revise supplied information to ensure it conforms to institutional guidelines and they generate catalogue records for deposited data incorporating cataloguing and documentation standards to ensure that information about those items can be made available to users through appropriate catalogues. In many cases the contextual information for resources will be crucial to their future use and this aspect of documentation should not be overlooked.

The level of cataloguing and documentation accompanying or subsequently added to an item, and any limitations these may impose, can be documented for the benefit of future users. Where data resources are managed by third parties but made available via an institution, information may be supplied by the third party in an agreed form which conforms to institution guidelines or in the supplier's native format.

Where a need for enhanced access exists, an Institution may undertake to enhance documentation and cataloguing information to a higher standard to meet new requirements. Retrospective documentation or catalogue enhancement should also occur when the validation or audit of the documentation and cataloguing for a resource shows this to be below a minimum acceptable standard.

A significant number of both users and suppliers of preservation metadata have adopted PREMIS and many of the initial obstacles to implementation have been addressed by them. The process of implementing PREMIS in a working environment is made easier by a number of tools which can extract metadata from digital objects and output PREMIS XML. The PREMIS Maintenance Activity maintains a webpage listing the most important tools available for use with PREMIS. It also includes an active email discussion list and a wiki for sharing documents. For further information see Resources and case studies below.

See also related sections of the Handbook including Acquisition and appraisal, and Preservation planning.

Resources

![]()

PREMIS Data Dictionary for Preservation Metadata, Version 3.0

http://www.loc.gov/standards/premis/v3/index.html

The PREMIS Data Dictionary and its supporting documentation is a comprehensive, practical resource for implementing preservation metadata in digital archiving systems. The Data Dictionary is built on a data model that defines five entities: Intellectual Entities, Objects, Events, Rights, and Agents. Each semantic unit defined in the Data Dictionary is a property of one of the entities in the data model. Version 3.0 was released in June 2015 (273 pages).

Preservation Metadata (2nd edition), DPC Technology Watch Report

http://dx.doi.org/10.7207/twr13-03

This report focuses on new developments in preservation metadata made possible by the emergence of PREMIS as a de facto international standard. It focuses on key implementation topics including revisions of the Data Dictionary; community outreach; packaging (with a focus on METS), tools, PREMIS implementations in digital preservation systems, and implementation resources. Published in 2013 (36 pages).

![]()

Tools for preservation metadata implementation

http://www.loc.gov/standards/premis/tools_for_premis.php

The PREMIS Maintenance Activity maintains a webpage listing the most important tools available for use with PREMIS. This contains entries on tools, in addition to pointers to others which may be used to generate METS (Metadata Encoding and Transmission Standard - an XML schema for packaging digital object metadata) files in conjunction with PREMIS. The majority of the tools listed are for extracting technical metadata from digital objects and converting it for encoding within the PREMIS Object entity. Others can be used for checking formats, or validating files against checksums

![]()

PREMIS website

http://www.loc.gov/standards/premis/index.html

The PREMIS Editorial Committee coordinates revisions and implementation of the PREMIS standard, which consists of the Data Dictionary, an XML schema, and supporting documentation. The PREMIS Implementers' Group forum, hosted by the PREMIS Maintenance Activity, includes an active email discussion list and a wiki for sharing documents. The wiki is a particularly useful resource for new implementers, as it includes materials from PREMIS tutorials, a collection of examples of PREMIS usage and links to information on PREMIS tools. The PREMIS Maintenance Activity maintains an active registry of PREMIS implementations.

Documenting your data

http://www.data-archive.ac.uk/create-manage/document

An excellent set of resources to assist researchers with the documention and metadata for their research studies, drawn together by the UK Data Archive.

Archaeology Data Service Guidelines for Depositors

http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/advice/guidelinesForDepositors

The ADS Guidelines for Depositors provide guidance on how to correctly prepare data and compile metadata for deposition with ADS and describe the ways in which data can be deposited. There is also a series of shorter summary worksheets and checklists covering: data management; selection and retention; preferred file formats and metadata. Other resources for the use of potential depositors include a series of Guides to Good Practice, which complement the ADS Guidelines and provide more detailed information on specific data types.

Case studies

![]()

DPC case note: British Library ASR2 using METS to keep data and metadata together for preservation

http://www.dpconline.org/component/docman/doc_download/474-casenoteasr2.pdf

This Jisc-funded case study examines the 'Archival Sound Recordings 2' project from the British Library, noting that one of the challenges for long term access to digitised content is to ensure that descriptive information and digitised content are not separated from each other. The British Library has used a standard called METS to prevent this. July 2010 (4 pages).

Designing Metadata for Long-Term Data Preservation:DataONE Case Study

https://doi.org/10.1002/meet.14504701435

A short description of how PREMIS was utilized to specify the requirements for preservation metadata for DataONE (Data Observation Network for Earth) science data. 2010 (2 pages).

Preservica Case Study: Q&A with Glen McAninch, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives

ttps://preservica.com/uploads/resources/Preservica-Kentucky-QA-2014_NEW.pdf

Glen McAninch discusses the Importance of Provenance, Context and Metadata in Preserving Digital Archival Records.

PREMIS Implementations Registry

http://www.loc.gov/standards/premis/registry/index.php

The PREMIS Maintenance Activity maintains an active registry of over 40 PREMIS implementations with details of the repository and its use of PREMIS. Although not formally case studies, entries have details of practical experience e.g., Creating a digital repository at the Swedish National Archives using PREMIS.

References

Gartner, R. and Lavoie, B., 2013. Preservation Metadata (2nd edition), DPC Technology Watch Report 13-3 May 2013. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.7207/twr13-03

PREMIS, 2013. Data Dictionary for Preservation Metadata, Version 3.0. Available: http://www.loc.gov/standards/premis/v3/index.html

Access

Illustration by Jørgen Stamp digitalbevaring.dk CC BY 2.5 Denmark

Introduction

There has always been a strong link between preservation and access. The major objective of preserving the information content of traditional resources is so that they can remain accessible for both current and future generations. Preserving access to digital objects is the key objective of digital preservation programmes but requires more active management throughout the lifecycle of the resource before it can be assured. It is, therefore, essential to consider issues important to access provision from the beginning of the preservation process, ideally as early as the acquisition phase. This is represented within the Decision Tree for Selection of Digital Material for Long-Term Retention included within the Acquisition and appraisal section of this handbook. With this in mind this section aims to identify the main issues that must be considered, the decisions that should be made when planning for access provision and how these may impact on preservation more generally.

Understanding users

Understanding potential users is essential when planning for the provision of access to digital objects as well as being a key consideration of broader digital preservation activities. The importance of such work is perhaps most evident in the focus on 'Designated Communities' within the Open Archival Information System Reference Model. Knowledge gained about these potential users will inform decisions made throughout the lifecycle but will likely hold most weight when choosing suitable access delivery solutions, balanced with resource and technological considerations. It is important to approach the identification of user communities and their needs systematically and objectively. In short, understanding what users want to do and what functionality can be provided by the repository.

The methodology used for the gathering of this information will vary depending on the organisational context. Potential options and tools may include the following:

- Analysis of current usage (access requests for both physical and digital objects, website statistics etc.)

- Surveys

- Focus groups

- Interviews

- Use cases

- Task analysis

When carrying out user analysis it is important to consider both existing users and non-users. Although interaction with non-users is inherently more difficult this can be a useful process towards understanding current barriers to use as well as identifying potential new market sectors.

Once collected this information should be used to inform decisions that are made in relation to the implementation of access delivery solutions. It is also important to continue to monitor the development of user communities and this should be incorporated in the standard Preservation planning activities within your organisation.

Access formats

A key consideration when planning for access is the format in which the digital objects will be delivered to the users. While there is a strong link between preservation and access in terms of the overriding objective of a digital preservation programme, there is also a need to make a clear distinction between them. There may be a combination of technical, legal, and pragmatic reasons to separate the access copy from the preservation copy, so it may be desirable or even necessary, to deliver an access copy of the digital object to the user in a different format from that held within the preservation system's storage. Indeed, an organisation may wish to offer different 'flavours' of format depending on the needs of the particular user or community in question. When selecting formats for access there are several questions an organisation will need to consider, these may include the following:

- What is the mostly commonly used/widely supported format for the object type?

- Will users have access to free viewers/software that support the proposed file type?

- What file size is produced and what are the implications for delivery to the user?

- Is the format easy to use?

- Will users require guidance or supporting documentation to allow them to access/use the objects?

- Does the organisation have separate user communities with different requirements for access?

See also File formats and standards for details of common preservation and access formats.

Legal issues for access

There are a variety of different legal issues that will probably need to be addressed when providing access to digital objects that will affect both the technological solutions that are deployed as well as who can access the material and when. This is one of the main access considerations that overlaps with acquisitions, as mentioned above, and it is essential that the correct information is gathered at that time to facilitate access requirements later in the life cycle. Without this information it may not be possible to properly manage access and may open the organisation to a number of potential legal risks.

Legal issues to be considered will include:

- Restrictions of use relating sensitivity and data protection

- Agreed embargoes on content where early access may represent a breach of contract

- Management of intellectual property rights, e.g. copyright

Management of IPR, in particular, should be aligned with the acquisition process with careful consideration given to transfer and ownership agreements and copyright licences put in place at that time. Licences must clearly state permitted access and reuse permissions, including third party licensing. These must then be clearly represented in policy and procedures for access, whether managed through a rights management system or by other methods.

Forms of access provision

The final key decisions an organisation must make are in the form of:

- Policy

- Procedure

- Free or charged services

- Online/Offline access, and the access environment provided

- Access for the disabled

- Storage and security

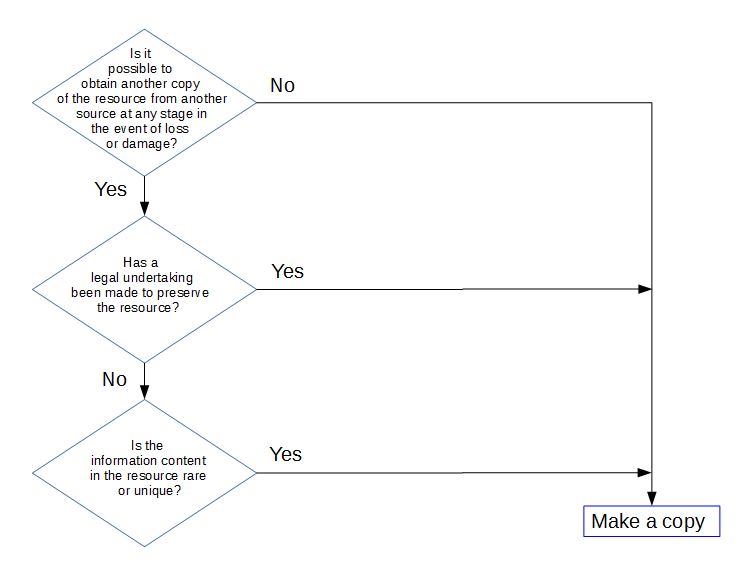

If the access copy is the only copy of a digital resource, then the danger of loss from theft or damage is clearly very high. If this approach is taken a risk assessment needs to be undertaken consisting of some of the following questions (See also Acquisition and appraisal and Storage):

Conclusions

Access is closely linked to many other digital preservation issues and technologies covered in the Handbook. In particular you may wish to look at Institutional policies and strategies, Legal compliance, Metadata and documentation, Acquisition and appraisal, Storage, Legacy media, File formats and standards, and Information security.

Resources

![]()

Born-Digital Access in Archival Repositories: Mapping the Current Landscape, Preliminary Report August 2015

https://docs.google.com/document/d/15v3Z6fFNydrXcGfGWXA4xzyWlivirfUXhHoqgVDBtUg/preview?sle=true#

This interesting document represents preliminary findings and analysis of a study and survey on current born-digital access practices in over 200 cultural heritage institutions. Respondents were primarily from the USA.

Reference model for an open archival information system (OAIS): Recommended practice (CCSDS 650.0-M-2: Magenta Book), Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems 2012

https://public.ccsds.org/pubs/650x0m2.pdf

This was later published as ISO 14721:2012, Space Data and Information Transfer Systems – Open Archival Information System (OAIS) – Reference Model, 2nd edition. The Access function within OAIS manages the processes and services by which consumers – and especially the Designated Community – locate, request, and receive delivery of items residing in the OAIS's archival storage. As such, it is the primary mechanism by which the archive meets its responsibility to make its information available to its user community. (135 pages).

Adrian Brown 2013 Practical Digital Preservation a how-to guide for organizations of any size

Chapter 9 (28 pages) of this book is devoted to the topic of providing access to users.

![]()

Community Owned digital Preservation Tool Registry COPTR

http://www.digipres.org/tools/

There are a large number of tools for access or that have access functionality incorporated in them. The Handbook recommends searching for them via the POWRR Grid tool within COPTR. The POWRR Tool Grid provides a set of interactive views designed to help practitioners identify and select tools that they need to solve digital preservation challenges. The Access, Use and Reuse column of the Grid identifies access tools for specific types of content or generic tools and systems that have access functions. Everything in the Grid is hyperlinked, so simply click through the displays until you find the information you are looking for. Clicking on the name of a specific preservation tool will reveal more detail on the COPTR wiki, which is where you should go to expand or update the tools information.

AIMS Born-Digital Collections: An Inter-Institutional Model for Stewardship. University of Hull, Stanford University, University of Virginia, and Yale University (2012)

http://dcs.library.virginia.edu/files/2013/02/AIMS_final.pdf

The AIMS (An Inter-Institutional Model for Stewardship) framework is a methodology for stewarding born-digital materials. It is divided into four main sections for high-level best practices for born-digital workflows: collection development, accessioning, arrangement and description, and discovery and access. Access primarily focuses on redaction and sensitive information. The appendices include, for example, sample processing workflow diagrams, an analysis of tools, and donor surveys. (195 pages).

Case studies

![]()

TNA case studies: Online access

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/archives-sector/online-access.htm

a series of nine case studies published by TNA on how collections have been made more accessible by putting records online. They are drawn from a wide variety of archives.

Codebreakers: makers of modern genetics

https://digirati.com/work/galleries-libraries-archives-museums/case-studies/wellcome-library/

A case study by digirati, the developers of the Wellcome Trust Library player focussing on the player its use in accessing the Francis Crick collection.The Wellcome Library's digital player is freely available for anyone to download and use. The player can be used to display all types of digital content, including cover-to-cover books, archives, works of art, videos and audio files. The software can be downloaded from the Wellcome Library GitHub account (https://github.com/wellcomelibrary/player).

Managing Risk with a Virtual Reading Room: Two Born Digital Projects, Michelle Light

http://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1462&context=lib_articles

Between 2010 and 2013, the University of California, Irvine, launched a site to provide online access to the personal papers of Richard Rorty and Mark Poster in the form of a virtual reading room. The virtual reading room mitigated the risks involved in providing this kind of access to personal, archival materials with privacy and copyright issues by limiting the number of qualified users and by limiting the discoverability of full-text content on the open web. The case study goes through each phase of research and thinking, including comparable projects happening at other institutions and lessons learned in a very open and informative way.

From Accession to Access: A Born-Digital Materials Case Study, by Cyndi Shein Journal of Western Archives Volume 5 Issue 1 (2014): 1-42

http://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1036&context=westernarchives

Between 2011 and 2013 the Getty Institutional Records and Archives made its first foray into the comprehensive ingest, arrangement, description, and delivery of unique born-digital material when it received oral history interviews generated by some of thePacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. project partners. This case study touches upon the challenges and affordances inherent to this hybrid collection of audiovisual recordings, digital mixed-media files, and analog transcripts. It describes the Archives' efforts to develop a basic processing workflow that applies the resource-management strategy commonly known as "MPLP" in a digital environment, while striving to safeguard the integrity and authenticity of the files, adhere to professional standards, and uphold fundamental archival principles. The study describes the resulting workflow and highlights a few of the inexpensive technologies that were successfully employed to automate or expedite steps in the processing of content that was transferred via easily-accessible media and consisted of current file formats.

Preservation action

Illustration by Jørgen Stamp digitalbevaring.dk CC BY 2.5 Denmark

Introduction

We know by now that digital preservation is comprised of a series of challenges emanating from organisational, resourcing, managerial, cultural, and technical issues. This section of the Handbook will focus specifically on actions that can be taken to help mitigate the technical challenges of preserving digital materials over time.

Technological obsolescence of formats

Technological obsolescence has long been considered a significant challenge of long term digital preservation. However in recent years studies have suggested that format obsolescence isn't always as prevalent as previously feared (Rosenthal 2015a, Jackson 2012). It is one issue that must be recognised and countered if digital materials are to survive over generations of technological change but It is certainly not the only challenge. Many established file formats are still with us, still supported, and still usable. It is quite likely that the majority of file formats you deal with will be commonly understood and well supported rather than obsolete.

A simple definition of obsolescence is the process of becoming outdated or no longer used. When talking about technological obsolescence, we refer for example to 'this Wordperfect 3.1 software is obsolete' or 'this BBC Micro computer is obsolete'. The exact moment at which obsolescence occurs can be difficult to pinpoint, particularly for materials that have only recently become obsolete. For example, just because the original application (e.g. MS Word) no longer supports a given format, it doesn't mean no other software that can read the format is unavailable. Similarly one institution may continue to use and maintain a piece of legacy software long after others have upgraded to new versions. It is perhaps therefore more useful to talk about 'institutional obsolescence', namely that the technology in question is no longer in use or easily accessed by a particular institution.

Obsolescence is an issue because all files have their own hardware and software dependencies. This was particularly the case in the early days of computing.

Change becomes an issue when it compromises the meaning of the content or its interpretation by a user. A core goal of digital preservation actions is to preserve the integrity and authenticity of the material being preserved, despite these generational changes in computing technology. In the next section we will discuss some common strategies to help minimise these changes.

Preservation strategies

In this section we review the technical strategies that can be employed to preserve digital information. After a flurry of activity in the late 1990s there has been relatively little progress in finding new strategies, though there has been significant research and development into varying implementation options and supporting technologies such as quality assurance, digital forensics (see Digital forensics), and technical representation information registries (see Technical solutions and tools in the Handbook). The techniques we will cover here are:

- Format Migration

- Emulation

- Computer Museums

Format migration

Format Migration is one of the most widely utilised preservation strategies employed and most digital preservation systems contain functionality or system data that assumes a migration solution. Format migration is different from storage media migration. It involves transferring or transforming (i.e. migrating) data from an ageing/obsolete format to a new format, possibly using new applications systems at each stage to interpret information. Moving from one version of a format standard to a later standard is a version of this method; for example moving from MS Word Version 6 (from 1993) to MS Word for Windows 2010. For frameworks and tools that are helpful for evaluating technical obsolescence of file formats see File formats and standards.

Format migration, like any intervention that has the potential to change the structure and content of data, can introduce errors and loss of information. Therefore, it is important to define metrics to measure possible loss of information and use these to do tests on the correctness and quality of format migration.

Recent work touching on quality assurance and digital preservation actions includes the work of the AQUA, SPRUCE, and SCAPE projects. To measure error rates, it is necessary to determine some very specific metrics. You might need to define what you count as an error and whether you weight some errors as being more important than others. This depends on the context/content of the record and what characteristics of the material are deemed 'significant' to preserve, as well as the migration tools and successive formats used in any migration pathway.

Some practical issues involved in this process include when to migrate – is it better to migrate from generation to generation, or should some generations be skipped? You will need to keep a record of all transformations, their results and to document detected losses of information so as to maintain evidence of authenticity and authority. PREMIS can be a useful tool for this - see the Handbook section on Metadata and documentation for more information about this standard. It is good practice always to retain the original file format as deposited to return to if required.

Emulation

Emulation offers an alternative solution to migration that allows archives to preserve and deliver access to users directly from original files. This technique attempts to preserve the original behaviours and the look and feel of applications, as well as informational content. It is based on the view that only the original programme is the authority on the format and this is particularly useful for complex objects with multiple interdependencies, such as games or interactive apps.

An emulator, as the name implies, is a programme that runs on a current computer architecture but provides the same facilities and behaviour as an earlier one. This approach has been endorsed by a number of heritage organisations, often in collaboration with technical experts and in recent years there has been some notable success in implementing emulation solutions for cultural heritage (see Resources below) . However some significant challenges remain, not least there are often rights issues associated with software licensing that need to be resolved (Rosenthal 2015b).

A particular benefit of emulation is that a single solution can be deployed to provide access to a large number of objects, so long as all those objects require delivery on the same operating system or hardware stack. Use of legacy computing equipment may however prove difficult for users, though they will almost certainly be accessing an 'authentic' representation of the records. Of course emulators have to be built and maintained, requiring a pool of expertise to be available and this cannot always be assumed. New emulators will be needed as computer architectures become obsolete, and both of these present costs and resource needs.

Computer museums

This methodology proposes the keeping of computers and their systems software (operating systems, drivers, etc.) as well as the data and applications programmes. Effort must be expended to keep all platforms in good order, and to retain all the knowledge necessary to maintain and use the machines and their programmes. The idea relies on having a source of spare parts too, but these will dwindle, as will pools of expertise. Hence this strategy tends to be an interim measure rather than a long-term solution. Some formal museums do exist, such as the Computer History Museum in California and the Centre for Computing History in Cambridge. These typically maintain machines in working order though do not provide preservation services. See also the Legacy media section of the Handbook for further information on historic file formats and media.

Implementation

The DPC Technology Watch Reports are a particularly useful guide to most common genres and file formats (including email, social media, Audio-Visual, eBooks, e-Journals, GIS, CAD, web archiving etc.) and show which strategies tend to be used most commonly in each of these areas. Tools to assist with implementation of preservation strategies are discussed in the Technical solutions and tools area of the Handbook particularly in File formats and standards.

Resources

![]()

DPC Technology Watch Report series

http://www.dpconline.org/publications/technology-watch-reports

The DPC Technology Watch Report series is intended as an advanced introduction to specific issues for those charged with establishing or running services for long term access. They identify and track developments in IT, standards and tools which are critical to digital preservation activities. They are commissioned by experts on these developments and are thoroughly scrutinised by peers before being released.

Emulation & Virtualization as Preservation Strategies

This 2015 report on Emulation and Virtualization as Preservation Strategies by David Rosenthal was funded by the Mellon Foundation, the Sloan Foundation and IMLS. It concludes recent developments in emulation frameworks make it possible to deliver emulations to readers via the Web in ways that make them appear as normal components of Web pages. This removes what was the major barrier to deployment of emulation as a preservation strategy. Barriers remain, the two most important are that the tools for creating preserved system images are inadequate, and that the legal basis for delivering emulations is unclear, and where it is clear it is highly restrictive. Both of these raise the cost of building and providing access to a substantial, well-curated collection of emulated digital artefacts beyond reach. If these barriers can be addressed, emulation will play a much greater role in digital preservation in the coming years. (37 pages).

Systematic planning for digital preservation: evaluating potential strategies and building preservation plans

http://www.ifs.tuwien.ac.at/~becker/pubs/becker-ijdl2009.pdf

This article published in 2009 describes a systematic approach for evaluating potential alternatives for preservation actions and building thoroughly defined, accountable preservation plans for keeping digital content alive over time. The work was undertaken as part of the Europran Union-funded PLANETS project . (25 pages).

File format conversion

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/information-management/format-conversion.pdf

Format conversion may can help you maintain access and use of your information and mitigate risks that arise from obsolescence. This 2011 guidance from The National Archives gives you the steps you should go through in performing a file format conversion process. (29 pages).

What organizations are preserving software

http://qanda.digipres.org/1068/what-organizations-are-preserving-software

This post and responses from August 2015 on the Digital Preservation Q&A site provides a useful list and links for institutions preserving software for emulation strategies.

SCAPE Project Final best practice guidelines and recommendations

http://scape-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/SCAPE_D20.6_KB_V1.0.pdf

This SCAPE project report published in 2014 covers three major areas: implementation of large-scale migration as a preservation strategy. Other areas are preservation of research data; and Bit preservation. (127 pages).

Case studies

![]()

The Internet Arcade

https://archive.org/details/internetarcade

The Internet Arcade is a web-based library of arcade (coin-operated) video games from the 1970s through to the 1990s from the Internet Archive, implemented using an in-browser emulation solution to provide access to the collection.

Rhizome

https://sites.rhizome.org/theresa-duncan-cdroms/

In the 1990s, Theresa Duncan and collaborators made three videogames that exemplified interactive storytelling at its very best. Two decades later, the works (like most CD-ROMs) have fallen into obscurity. This online exhibition, co-presented by Rhizome and the New Museum brings them back, making them playable online via emulation.

Assessing Migration Risk for Scientific Data Formats

http://www.ijdc.net/index.php/ijdc/article/view/202/271

This paper explore a simple hypothesis – that, where migration paths exist, the majority of scientific data files can be safely migrated leaving only a few that must be handled more carefully – in the context of several scientific data formats that are or were widely used. The approach is to gather information about potential migration mismatches and, using custom tools, evaluate a large collection of data files for the incidence of these risks. The results support the initial hypothesis, though with some caveats.

Portico - Preservation Step-by-Step

https://www.portico.org/our-work/preservation-step-step/

A useful step by step guide to the preservation planning and migration strategies employed by Portico The preservation plan may include an initial migration of the packaging or files in specific formats (for example, Portico migrates publisher specific e-journal article XML to the NLM archival standard).

Trash to treasure: Retro computer, software collection helps National Library access digital pieces

The National Library of Australia made public its own efforts to develop a collection of legacy computing hardware and software. It uses it to support data recovery and then implements other preservation strategies and does not rely on the computer museum for long-term preservation.

References

David Rosenthal, 2015a. "The Prostate Cancer of Preservation" Re-examined. Available: http://blog.dshr.org/2015/09/the-prostate-cancer-of-preservation-re.html

David Rosenthal, 2015b. Emulation & Virtualization as Preservation Strategies. Available: https://mellon.org/media/filer_public/0c/3e/0c3eee7d-4166-4ba6-a767-6b42e6a1c2a7/rosenthal-emulation-2015.pdf

Andrew N. Jackson, 2012. Formats over Time: Exploring UK Web History,. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1210.1714

Preservation planning

Illustration by Jørgen Stamp digitalbevaring.dk CC BY 2.5 Denmark

What is preservation planning?

Preservation planning is the function within a digital repository for monitoring changes that may impact on the sustainability of, or access to, the digital material that the repository holds. It should be proactive: both current and forward-looking in terms of acquisitions and trends. Changes might occur within the repository, within the organisation in which the repository resides, or external to the repository and organisation themselves. Changes might be monitored in the following areas:

- Technology watch

packaging

storage

formats

tools

environment

access mechanisms

- Designated communities

needs and expectations of users

needs and expectations of producers

emerging tools for machine to machine access

formal feedback from users and producers

The concept of preservation planning is defined within the functional model of the OAIS standard (CCSDS, 2012). This section focuses primarily on the Monitoring components within the OAIS definition. The 'Monitor Technology' and 'Monitor Designated Community' functions of OAIS provide surveys that inform preservation planning activities. These alert the repository about changes in the external environment and risks that could impact on its ability to preserve and maintain access to the information in its custody, such as innovations in storage and access technologies, or shifts in the scope or expectations of the Designated Community (see Lavoie, 2015,13). Preservation planning then develops recommendations for updating the repository's policies and procedures to accommodate these changes. The Preservation planning function represents the OAIS's safeguard against a constantly evolving user and technology environment. It detects changes or risks that impact the repository's ability to meet its responsibilities, designs strategies for addressing them, and assists in the implementation of these strategies within the archival system.

What is the purpose of preservation planning?

Identifying triggers for taking action to preserve digital materials

Where change has been identified, a risk assessment process can be used to analyse and identify the change that represents a significant risk to the digital material in the repository. Risks can then be addressed and hopefully mitigated following a preservation planning exercise to decide on appropriate preservation action. In this case, the monitoring or technology watch process is identifying trigger points for further analysis, preservation planning and, where relevant, action to preserve digital materials.

Building a knowledge base to inform preservation activities

The process of monitoring internal and external factors as part of a preservation planning activity can inform the knowledge base of an organisation, and in doing so improve its ability to perform digital preservation activities effectively. For example the "knowledge base" of an organisation might be augmented with information about the capabilities of a new software tool, or the obsolescence and unavailability of an existing tool. In some cases this process might be best performed individually or within an organisation, but alternatively might be more usefully performed in a collaborative manner. The vast depth and breadth of knowledge required for digital preservation naturally favours a collaborative approach, whereby particular organisations are able specialise in a particular area and contribute that knowledge to an open or shared knowledge base.

Implementations of a preservation planning service

The degree to which technology watch will be necessary will vary according to the degree of uniformity or control over formats and media that can be exercised by the institution. Those with little control over media and formats received and a high degree of diversity in their holdings will find this function essential. For most other institutions the IS strategy should seek to develop corporate standards so that everybody uses the same software and versions and is migrated to new versions as the products develop.

Failure to implement an effective technology watch or IS strategy incorporating this will risk potential loss of access to digital holdings and higher costs. It may be possible for example to re-establish access through digital forensics (see Digital forensics) but this may be expensive compared to pre-emptive strategies.

A retrospective survey of digital holdings (see Getting started) and a risk assessment and action plan (see Risk and change management) may be a necessary first step for many institutions, prior to implementing a technology watch.

Good preservation metadata in a computerised catalogue identifying the storage medium, the necessary hardware, operating system and software will enable a technology watch strategy (see Metadata and documentation).

Integrated preservation systems, and individual tools and registries can also support this function (see Technical solutions and tools).

Resources

Some of the core preservation watch activities are generic and therefore ready made for collaboration while others are highly localised and not easily shared.

![]()

DPC Technology Watch Report Series

http://www.dpconline.org/advice/technology-watch-reports

These reports provide an advanced introduction to specific issues for those charged with establishing or running services for long term preservation and access. They are updated and new reports added periodically.

Scout – a preservation watch system, OPF blog post 16th Dec 2013

http://openpreservation.org/blog/2013/12/16/scout-preservation-watch-system/

The SCAPE Project designed a demonstrator for an automated preservation watch service, called SCOUT. SCOUT was described by its developers as providing "...an ontological knowledge base to centralize all necessary information to detect preservation risks and opportunities. It uses plugins to allow easy integration of new sources of information, as file format registries, tools for characterization, migration and quality assurance, policies, human knowledge and others."

Assessing file format risks: searching for Bigfoot? OPF Blog post 29th Oct 2014

http://openpreservation.org/blog/2013/09/30/assessing-file-format-risks-searching-bigfoot/

This detailed blog post raises concerns about challenges with automating preservation watch.

Barbara Sierman, Paul Wheatley 2010 Evaluation of Preservation Planning within OAIS, based on the Planets Functional Model Planets Deliverable no. PP7-D6.1

http://www.planets-project.eu/docs/reports/Planets_PP7-D6_EvaluationOfPPWithinOAIS.pdf

The Planets Project realised various aspects of the concepts defined within the OAIS Preservation Planning function, and performed an evaluation of OAIS based on these practical experiences. 2010 (34 pages).

![]()

Community Owned digital Preservation Tool Registry COPTR

http://coptr.digipres.org/Main_Page

COPTR describes tools useful for long term digital preservation and acts primarily as a finding and evaluation tool to help practitioners find the tools they need to preserve digital data. COPTR aims to collate the knowledge of the digital preservation community on preservation tools in one place. It was initially populated with data from registries run by the COPTR partner organisations, including those maintained by the Digital Curation Centre, the Digital Curation Exchange, National Digital Stewardship Alliance, the Open Preservation Foundation, and Preserving digital Objects With Restricted Resources project (POWRR). COPTR captures basic, factual details about a tool, what it does, how to find more information (relevant URLs) and references to user experiences with the tool. The scope is a broad interpretation of the term "digital preservation". In other words, if a tool is useful in performing a digital preservation function such as those described in the OAIS model or the DCC lifecycle model, then it's within scope of this registry.

Case studies

OCLC Research Report - Preservation Health Check: Monitoring Threats to Digital Repository Content

http://www.oclc.org/research/themes/research-collections/phc.html

The OCLC Research Preservation Health Check activity was initiated by Open Planets Foundation. The Pilot used a sample of preservation metadata provided by the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. The report presents the preliminary findings of Phase 1 of the Pilot and suggests that there is an opportunity to use PREMIS preservation metadata as an evidence base to support a threat assessment exercise based on the Simple Property-Oriented Threat (SPOT) model.

Digital Preservation Planning Case Study

Presentation on getting started with digital preservation planning, including scoping, risk assessing and prioritising your collection (including legacy media examples), and staff roles and responsibilities. 2013 (20 pages).

References

Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems, 2012. Reference model for an open archival information system (OAIS): Recommended practice (CCSDS 650.0-M-2: Magenta Book), CCSDS, Washington, DC. Available: https://public.ccsds.org/pubs/650x0m2.pdf

(Note this is a free to download version of ISO 14721:2012, Space Data and Information Transfer Systems – Open Archival Information System (OAIS) – Reference Model, 2nd edn).

Lavoie, B., 2014. The Open Archival Information System (OAIS) Reference Model: Introductory Guide (2nd Edition) DPC Technology Watch Report 14-02 October 2014. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.7207/TWR14-02

Legacy media

Illustration by Jørgen Stamp digitalbevaring.dk CC BY 2.5 Denmark

Introduction

Many organisations will have large amounts of data stored on legacy media, such as magnetic and optical media, and data will continue to be received on old carriers. Ultimately, the best long-term strategy for the preservation of the data will be migration to file-based storage and active management thereafter (see Storage section). Often the original media will continue to be preserved alongside this, so it will be necessary to understand their preservation and storage requirements. For organisations with large collections of legacy media, understanding the risks facing each media type will also help with prioritising collections for migration and application of digital forensics tools and methods will also be helpful (see Digital forensics section).

For the preservation of magnetic and optical media, two aspects need to be considered - the media itself and the hardware and software needed to interpret it. In some cases the second aspect will be the most challenging. As the popularity of a media format declines, the manufacture of hardware ceases and becomes more difficult to procure and maintain.

Preserving legacy media

In most cases, the simplest way to mitigate risks with storage media is to transfer all content into a managed storage system. This means that the content can be managed without reference to the original storage medium. This would probably be adequate for the vast majority of digital content requiring preservation. However, there may be a few instances where it is necessary to retain the original media carrier in some way. In some cases, the storage medium could simply be retained as an artifact, with no expectation of long-term access, e.g. where it forms part of a hybrid collection or has some kind of value by association. (e.g. part of the collections of a prominent author). However, where continued access to the content is required, careful thought needs to be given to how it could be accessed in the future.

One thing that we do know from experience is that digital storage media types change frequently over time. For example, the previous version of this handbook contained an overview of magnetic and optical storage media and provided estimates of the lifetimes of selected storage media types that were popular in the mid-1990's (a digital preservation handbook written in previous decades would presumably have included assessments of punched cards and paper tape). Given current trends in storage technology, it is perhaps better now to provide a framework that supports the ongoing evaluation of storage media, which might now include flash memory sticks or external hard-drives. One such framework has been provided by The National Archives (Brown, 2008). This uses a scorecard approach, measuring selected storage media against six criteria:

- longevity (e.g., proven operational lifetimes)

- capacity

- viability (e.g., in terms of retaining evidential integrity)

- obsolescence

- cost

- susceptibility (e.g., to physical damage and to different environmental conditions).

In practice, however, these kinds of assessment can only get you so far. There is a growing body of evidence that suggests that variation in manufacturing quality also plays a major role in media longevity (Harvey, 2011). That is why, in the end, digital preservation normally depends upon the transfer of content from media into a managed storage environment.

Resources

![]()

Selecting storage media for long-term preservation, TNA Digital Preservation Guidance Note 2: August 2008

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/selecting-storage-media.pdf

This document is one of a series of guidance notes produced by The National Archives,giving general advice on issues relating to the preservation and management of electronic records. It is intended for use by anyone involved in the creation of electronic. It provides information for the creators and managers of electronic records about the selection of physical storage media in the context of long-term preservation. Note guidance is as of August 2008. (7 pages).

Care, Handling and Storage of Removable media, TNA Digital Preservation Guidance Note 3: August 2008

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/information-management/removable-media-care.pdf

This document is one of a series of guidance notes produced by The National Archives,giving general advice on issues relating to the preservation and management ofelectronic records. It provides advice on the care, handling and storage of removable storage media. Note guidance is as of August 2008. (10 pages).

You've Got to Walk Before You Can Run: First Steps for Managing Born-Digital Content Received on Physical Media

http://www.oclc.org/content/dam/research/publications/library/2012/2012-06.pdf

A step by step guide about getting digital born material off of various physical media. It focuses on identifying and stabilizing your holdings so that you'll be in a position to take additional steps as resources, expertise, and time permit. The POWRR project document Resources for Technical Steps (3 pages) adds additional resources for some of the steps. (7 pages).

![]()

Kryoflux: Commercial tool for reading floppy disks

KryoFlux is a USB-based device designed specifically to acquire reliable low-level reads suitable for software preservation. This is the official hardware developed by The Software Preservation Society,

![]()

Digital Preservation Management: Chamber of Horrors

http://dpworkshop.org/dpm-eng/oldmedia/disks.html

Some examples of obsolete and endangered disks.

Lost Formats

http://www.experimentaljetset.nl/archive/lostformats

Web page from the Lost Formats Preservation Society with a very nice overview of silhouettes of the shapes to allow quick identification and key brief history and features such as dimensions and storage capacity. All silhouettes shown as same size rather than to scale. Last major update appears to be c.2008 but content is still valuable for all but the most recent formats.

Museum Of Obsolete Media

http://www.obsoletemedia.org/category/format/

Great resource covering a very wide-range of obsolete audio, video, data, and film storage media. You can browse the categories or the Gallery and Timeline. Particularly good if you know what you are looking for and derived mostly from the relevant Wikipedia entries.

Case studies

![]()

A Fistful of Floppies: Digital Preservation in Action

https://ischool.uw.edu/sites/default/files/capstone/posters/JStanley_Capstone_Landscape.pdf

The University of Washington Library system currently holds a small collection of electronic thesis and dissertation (ETD) accompanying materials from the late 1980's to 2011 on floppy disks and CD-Rs. These materials will soon reach or have already exceeded the limit of their expected lifespans. This 2015 project looked at the digital preservation possibilities for this collection of materials using digital forensics as a model.(1 page).

Enford, D., et al 2008, Media Matters: developing processes for preserving digital objects on physical carriers at the National Library of Australia, Papers from 74th IFLA General Conference and Council

http://archive.ifla.org/IV/ifla74/papers/084-Webb-en.pdf

The National Library of Australia had a relatively small but important collection of digital materials on physical carriers, including both published materials and unpublished manuscripts in digital form. The Digital Preservation Workflow Project aimed to produce a semi-automated, scalable process for transferring data from physical carriers to preservation digital mass storage, helping to mitigate the major risks associated with the physical carriers. (17 pages).

Digital Preservation Planning Case Study

Presentation on getting started with digital preservation planning, including scoping, risk assessing and prioritising your collection (including legacy media examples), and staff roles and responsibilities. 2013 (20 pages).

References

Brown, A., 2008. Selecting storage media for long-term preservation. TNA Digital Preservation Guidance Note 2: August 2008. Available: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/selecting-storage-media.pdf

Harvey, R., 2011. Preserving Digital Materials 2nd edition. De Gruyter Saur.

Storage

Illustration by Jørgen Stamp digitalbevaring.dk CC BY 2.5 Denmark

Introduction

This section covers the emerging practice of using IT storage systems for digital preservation. It deals with generic issues and more specific issues associated with cloud storage are addressed separately (see Cloud services section). The traditional practice of preserving of digital media, for example legacy items within existing collections is also covered elsewhere (see Legacy media section). Many organisations will have mixed strategies or will be in the process of transitioning from one to the other.

The use of storage technology for digital preservation has changed dramatically over the last twenty years. During this time, there has been a change in practice. Previously, the norm was for storing digital materials using discrete media items, e.g. individual CDs, tapes, etc., which are then migrated periodically to address degradation and obsolescence. Today, it has become more common practice to use resilient IT storage systems for the increasingly large volumes of digital material that needs to be preserved, and perhaps more importantly, that needs to be easily and quickly retrievable in a culture of online access. In this way, digital material has become decoupled from the underlying mechanism of its storage. With this come consequent benefits of allowing different preservation activities to be handled independently.

Resilient storage systems

A resilient IT storage system consists of storage media contained within a server that provides built in resilience to various failure modes by using inbuilt redundancy and recovery. For example, a storage system might be hard disk drives in a Redundant Array of Independent Disks (RAID), data tapes in a tape library, or a combination of storage types in a Hierarchical Storage Management system (HSM). It can include onsite storage and/or remote cloud storage and automated replication of digital materials across multiple sites and systems.

These systems will still become obsolete over time and digital materials should be migrated regularly between storage systems as they become obsolete. Migration between storage systems is separate to migration between file formats and can be handled largely as an IT issue, with the proviso that proper oversight is employed to ensure preservation requirements are met. The upside is that the use of IT systems for data storage can provide much faster access, a more scalable solution, easier management, and ultimately lower costs especially at scale.

It is critical to understand the difference between standard IT storage solutions and the additional needs of long-term preservation. It is essential to be able to explain these differences to your IT department or storage service provider and to be able to specify these requirements when procuring a system or service. Standard storage systems are designed for digital objects that are in active use. While backup procedures are usually included, they generally do not meet the more stringent requirements to ensure long-term preservation of digital materials. Backup and digital preservation are not the same thing and many IT departments or experts may not appreciate this. Preservation storage systems require a higher level of geographic redundancy, stronger disaster recovery, longer-term planning, and most importantly active monitoring of data integrity in order to detect unwanted changes such as file corruption or loss.

There are many ways of meeting requirements for preservation storage and these will vary in scale and complexity depending on organisational context. It will be necessary to assess in-house resources and consider out-sourcing and cloud storage options. The approach taken will often depend on the collection size and complexity of collection and the resources that are available within the organisation. It is possible to meet preservation storage requirements with a basic set-up, but as a collection increases in size it will be necessary to address issues such as scalability and automation.

Principles for using IT storage systems for digital preservation |

|

|

The following represent principles that should be employed when designing or selecting storage systems for preservation. |

|

1 |

Redundancy and diversity

|

2 |

Fixity, monitoring, repair

|

3 |

Technology and vendor watch, risk assessment, and proactive migrations

|

4 |

Consolidation, simplicity, documentation, provenance and audit trails

|

Storage reliability

When looking at storage solutions, either onsite or cloud, the question arises of how reliable they are and if something goes wrong then what does this mean in terms of data loss. Manufacturers will typically assert statistics such as reliability, durability, failure rates and error rates.

For example, this might take the form of a cloud service being designed for 99.999% durability, a Bit Error Rate (BER) of 1 in 1016 when reading data from a data tape, or a Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF) of 1M hours for a hard drive. These numbers are then used to calculate further measures of reliability. For example, a Mean Time To Data Loss (MTTDL) of 1,000 years might be asserted when hard drives are used in a RAID6 array.

These numbers can be hard to understand, and they need to be interpreted with great care when attempting to estimate ‘how safe’ a given storage solution will be.

There has already been substantial work on how to describe, measure and predict storage reliability, including from a digital preservation perspective. This is a complex topic that is not possible to cover in this handbook. Some example references for further reading are Greenan et al (2010), Rosenthal (2010) and Elerath (2009). What comes from this work are several important considerations:

- IT Storage technology is in general remarkably reliable for what it does. Failures are relatively rare events, but they do and will happen. The temptation is to assume that just because at an individual level a particular type of failure hasn't been experienced then that storage technology is in general more reliable than it really is. This is dangerous position. For example, many people will have hard drives that have worked perfectly well for years and years, but the reality is that, on average, up to 5-15% of hard drives actually fail within one year (Backblaze, 2014), (Pinheiro et al, 2007).

- Because failures and errors are relatively rare events, reliability statistics from vendors are typically based on models and simulations and not from long-term observations of what actually happens in practice. For example, if a manufacturer says that the shelf life of media is 30 years then it's not because they have actually tested media over that time period. Likewise, if a vendor estimates the MTTDL is 1,000 years then they clearly haven't built a system and tested it for anywhere near that length of time. Therefore, statistics should be interpreted as best estimates from vendors of how a system might behave in practice - but it may not actually turn out that way. For example, field studies have suggested that manufacturer estimates of reliability can be over optimistic (Jiang et al, 2008) .

- The likelihood of data loss increases dramatically when correlations are taken into account. Correlations are where parts of a system, or different copies of the digital material, can't be considered as independent. If there is a problem with one part of the system or copy of the digital material then there is likely to be a problem with another part or copy. Examples include a manufacturing fault affecting all the hard drives in a storage server, software or firmware bugs systemically corrupting digital material, failure by an organisation to regularly test its backups, or failure to isolate or decouple storage systems so that if one copy of the digital material is accidentally deleted then all the other copies don't get deleted too. These correlation factors can be far more significant than the specific failure modes covered by reliability statistics.

These findings and observations result in the following recommendations:

- Plan for failures to happen in IT storage solutions no matter how cleverly designed by the manufacturer. Failure rates in practice may well be higher than manufacturer statistics suggest.

- Data loss can be caused by failure to put in place proper processes and procedures around the use of IT storage as well as from the storage technology itself. Proper risk assessment is the way to identify and manage these problems.

- The best strategy remains to create multiple independent copies of digital material in different locations and to store them using different technologies where possible. This should include a process of actively and regularly checking data integrity of all the copies so problems can be detected no matter why and where they might occur. In this way, risks are both minimised and spread, and reliance isn't placed on any particular storage technology or service being completely error free.

Multi-copy storage strategies

Digital storage technologies present several risks to long-term preservation of digital objects. These risks can be reduced by using a digital storage strategy that involves one or more storage systems and at least two copies of the data.

Good practice is for a storage strategy to have the following characteristics:

(a) multiple independent copies exist of the digital materials

(b) these copies are geographically separated into different locations

(c) the copies use different storage technologies

(d) the copies use a combination of online and offline storage techniques

(e) storage is actively monitored to ensure any problems are detected and corrected quickly.

A digital storage strategy can be implemented in a staged way, starting with a basic level of protection and access to digital content and moving on towards a more automated and scalable approach that gives a higher level of data safety and security.

Risks to digital content come from a range of sources and a digital storage strategy helps balance the cost of digital storage with the reduction of those risks. Example risks to consider include fire, flood, failure to instigate or follow proper processes or procedure, malicious attack, media degradation, and obsolescence of storage systems and technologies. The principal risks and means of addressing or mitigating them are often addressed in an organisation's business continuity planning (see Risk and change management).

It is important to realise that many examples of content loss are not necessarily due to technical faults with storage technology (although it is important to recognise that these do happen), but can come from human error, lack of budget or planning of storage migrations, or a failure to regularly check and correct failures that might occur.

In a world that is increasingly using networked systems and technologies for digital storage, there is a role for an offline copy of digital materials. This can provide a 'fire break' against problems with online systems that can automatically propagate between locations, e.g. deletion of a file in one location that automatically deletes a mirrored copy at another site.

Making more than one copy of the digital materials is fundamental to achieving a basic level of data safety. Using different types of storage for each copy helps spread the risk and ensure that a problem with one technology doesn't affect the others. The way each copy is stored can be adjusted to achieve an acceptable overall level of cost, risk and complexity. For example, one copy might be held using an online storage server for fast access and one copy might be on data tape in deep archive for low cost and relatively high safety.

This Handbook follows the National Digital Stewardship Alliance (NDSA) preservation levels (NDSA, 2013) below in recommending four levels at which digital preservation can be supported through storage and geographic redundancy. We make the additional recommendation of using a combination of online and offline copies to achieve a good combination of data access and data safety:

Level |

Approach |

Risks addressed and benefits achieved |

1 |

|

|

2 |

|

|

3 |

|

|

4 |

|

|

Managing storage system obsolescence and risks

The use of storage technologies and solutions needs careful planning and management to be an effective approach to supporting digital preservation. If done properly, the result can be very good levels of data safety, rapid access to content when needed, and costs that are both low and predictable.

IT storage technologies can fail or cause data corruption and the lifetime of media and systems is typically short, for example 3-5 years, which means solutions become obsolete quickly and migration is needed to avoid digital materials becoming at risk. Migration in this context means moving data off an old storage system and onto a new storage system. The digital material itself does not change but the storage solution does. An IT department or storage service provider will think of migration at the storage level. This is in contrast to file format migration where the file format will change, but the way that the files are stored doesn't change.

Resources

![]()

NDSA Levels of Preservation

http://www.digitalpreservation.gov/ndsa/activities/levels.html (2013)

https://ndsa.org//publications/levels-of-digital-preservation/ (Version 2.0, 2018)

The National Digital Stewardship Alliance (NDSA) "Levels of Digital Preservation" are a tiered set of recommendations for how organizations should begin to build or enhance their digital preservation activities. It is intended to be a relatively easy-to-use set of guidelines useful not only for those just beginning to think about preserving their digital assets, but also for institutions planning the next steps in enhancing their existing digital preservation systems and workflows. It is not designed to assess the robustness of digital preservation programs as a whole since it does not cover such things as policies, staffing, or organizational support.

These are some of the more notable digital preservation storage systems and storage system/service providers There are a wide-range of commodity IT storage vendors, as well as specialist digital preservation service providers that can provide onsite or cloud storage (see also Cloud services). These specialists typically may support other preservation functions in addition to storage.

Arkivum

Digital Preservation Network

DSpace

ePrints

Fedora

iRods

LOCKSS

OCLC Digital Archive CONTENTdm

http://www.oclc.org/digital-archive.en.html

Portico

http://www.portico.org/digital-preservation/

Preservica

Rosetta

https://www.exlibrisgroup.com/products/rosetta-digital-asset-management-and-preservation/

Community Owned digital Preservation Tool Registry COPTR

http://coptr.digipres.org/Main_Page

Although focussing principally on tools the COPTER registry also covers a range of storage systems and services. It acts primarily as a finding and evaluation tool to help practitioners find the tools they need to preserve digital data. COPTR captures basic, factual details about a tool, what it does, how to find more information (relevant URLs) and references to user experiences with the tool.

![]()

DSHR's Blog

David Rosenthal is a computer scientist and chief scientist for the LOCKSS project. His blog frequently covers computer storage development and trends and implications for digital preservation.

Case studies

![]()

The National Archives case study: Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/archives/case-study-oxford.pdf

This case study covers the Bodleian Library and the University of Oxford, and the provision of a "private cloud" local infrastructure for its digital collections including digitised books, images and multimedia, research data, and catalogues. It explains the organisational context, the nature of its digital preservation requirements and approaches, its storage services, technical infrastructure, and the business case and funding. It concludes with the key lessons they have learnt and future plans. January 2015 (4 pages).

The National Archives case study: Parliamentary Archives

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/archives/case-study-parliament.pdf

This case study covers the Parliamentary Archives. It is an example of an archive using a hybrid set of storage solutions (part-public cloud and part-locally installed) for digital preservation as the archive has a locally installed preservation system (Preservica Enterprise Edition) which is integrated with cloud and local storage and is storing sensitive material locally, not in the cloud. January 2015 (4 pages).

The National Archives case study: Tate Gallery

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/archives/case-study-tate-gallery.pdf

This case study discusses the experience of developing a shared digital archive for the Tate's four physical locations powered by a commercial storage system from Arkivum. It explains the organisational context, the nature of their digital preservation requirements and approaches, and their rationale for selecting Arkivum's on-premise solution, "Arkivum/OnSite" in preference to any cloud-based offerings. It concludes with the key lessons learned, and discusses plans for future development. January 2015 (4 pages).

References

Backblaze, 2014. Hard Drive Reliability Update – Sep 2014. Backblaze. [blog] Available: https://www.backblaze.com/blog/hard-drive-reliability-update-september-2014/

Elerath, J., 2009. Hard-Disk Drives: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Communications of the ACM. 52 (6), 38-45. Available: doi:10.1145/1516046.1516059. http://cacm.acm.org/magazines/2009/6/28493-hard-disk-drives-the-good-the-bad-and-the-ugly/fulltext