Handbook

Organisational activities

Illustration by Jørgen Stamp digitalbevaring.dk CC BY 2.5 Denmark

Who is it for?

Creators and publishers of digital resources, third-party service providers, operational managers (DigCurV Manager Lens) and staff (DigCurV Practitioner Lens) with responsibility for implementing institutional activities of relevance to digital preservation. It is assumed that these will include a) staff from structurally separate parts of the organisation, and b) a wide range of knowledge of digital preservation, from novice to sophisticated; c) both technical and non technical perspectives; d) a wide range of functional activities with a direct or indirect link to digital preservation activities.

Assumed level of knowledge

Wide-ranging, from novice to advanced.

Purpose

- To provide pointers to sources of advice and guidance aimed at encouraging good practice in creating and managing digital materials. The importance of the creator in facilitating digital preservation is stressed throughout the handbook but particularly in Creating digital materials. Good practice in digitisation and other digital materials creation is crucial to the continued viability of digital materials.

- To raise awareness of factors which need to be considered when creating or acquiring digital materials.

- To provide pointers to helpful sources of advice and guidance for both novices and those who have already begun to think through theimplications of digital technology on their operational activities.

Download a PDF of this section.

Business cases, benefits, costs, and impact

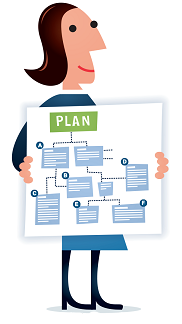

Illustration by Jørgen Stamp digitalbevaring.dk CC BY 2.5 Denmark

Introduction

Any change in the economic environment may mean that many organisations are challenged to reduce overall expenditure and to maximise efficiencies. At the same time organisations are preserving increasing amounts of digital material. Reuse of models can form a part of the response to this challenge. The long term management - preservation - of digital materials is an expensive and complex activity. It cannot reliably be done without the investment of resources and expenditure.

The challenges for an organisation are to create business models that:

- Can help define benefits and outcomes and convince key decision makers that it is a worthwhile endeavour;

- Support the wider aims and objectives of the parent organisation;

- Provide for the future of their digital materials in an economically sustainable way and helps reconcile the difference between short to mid-term funding commitments/funding cycles, and long-term preservation goals.

Other organisations have already created templates for business cases and models for the calculation of cost and benefit, so reusing some or parts of these models can not only save time but be used as justification for the adoption of particular strategies.

Business cases

The business case is a tool for advocating and ensuring that an investment is justified in terms of the strategic direction of the organisation and the benefits it will deliver. It typically provides context, benefits, costs and a set of options for key decision makers and funders. It can also set out how success will be measured to ensure that promised improvements are delivered.

It is essential that any business model or proposal that is created supports the wider aims and objectives of the parent organisation. It is equally important that key stakeholders, such as budget holders, are consulted and given early sight of the plans and offered the opportunity to comment and provide input. Early exposure of plans can to some extent mitigate situations in which plans might otherwise be rejected outright.

However, presenting a business case for preserving any material at an early stage is no guarantee that it will be accepted. Whilst there is no sure fire template, some or all of the following steps may be useful if a plan is rejected. Within an organisation there may be set procedures and policies regarding the making and presentation of business cases and these should be followed. Early communication of business planning can help identify topics or areas that could present problems when the plan is formally presented.

Identify options and be pragmatic

The point of business planning is to be aspirational and to create services or products that have value and benefit. Not everyone sees the benefits in preservation over the long term where costs are an ongoing issue or where resources are required to be committed for the long term. Business planning is often an exercise in pragmatism. It might be more effective to make a number of smaller more focussed business plans than one single large proposal. Using their knowledge of an organisation the author of a business plan must ensure that any plan is realistic and within the means of the organisation. Strategic planning provides the framework within which business plans are written. Any strategic objective can be achieved in a number of ways, e.g. less money but more time, fewer staff but longer timeframe etc. A pragmatic response offers decision makers a preferred option and why it is preferred and a small range of other alternative options in the business case. It is often helpful to include the "costs/dis-benefits of inaction" as an option against which other actions can be evaluated.

If at first you don't succeed

Work with stakeholders to identify reasons why a business plan was rejected. Talk to those involved in decision making and seek specific feedback. Was the cost component too expensive? Were the plans too ambitious? Is it felt the business case was poorly written or presented? Does the timeframe not fit with organisational plans?

Response: Work with stakeholders to address key concerns. Be clear to address each issue. Explain the reasons why a business plan was presented and what it is aiming to achieve. Focus on benefits, especially those that address the key strategic goals of the parent organisation. Focus on short as well as longer term benefits of the business plan. One approach is to create business plans that are 'SMART', that is Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and Timely.

When circumstances change

The hard work in business planning is getting to the point where a plan is accepted. However, circumstances can change. If a business plan is not implemented or previously agreed funding withdrawn, the implications can be severe. Again, communication with key stakeholders is essential and can reveal why something may have changed.

Response: Part of business planning involves having a range of options that can be offered in the event of problems arising with funding a preferred option. Having a well-structured business plan from which proposals can be deleted can help in making an alternative case for phased or alternative implementations requiring fewer resources. In such a case a business plan might quickly be re-drafted in more acceptable terms and resources made available. Having a focus on why resources were not made available gives an opportunity for a business case to be re-presented with more emphasis on benefits and positive impact.

Creating business cases

The following steps should be considered when writing and delivering a business case.

Creating a business case |

|

1. Audit your digital materials and prioritise work required |

Audit your digital materials. Analyse the risks and opportunities for your digital materials. Use your analysis to prioritise areas of work and assign owners to them. |

2. Is this the right time? |

What are you already doing? Is it the right time to do new things on your own? Can you collaborate with others? |

3. Institutional analysis |

How ready is your institution for change in terms of content and process? |

4. Stakeholder analysis and advocacy |

Who will be working on and using the digital materials? Who decides on funding? Engage with them using language and terms they will understand. |

5. Objectives: scope aims, activities, plan and costs |

Map out what are you going to do, who will do what, what will it cost, and when it will happen. |

6. Map benefits to organisational strategy |

Make sure you express the benefits of your business case in a way that your funders will understand. |

7. What else is needed? |

Do you need to include a cost-benefits analysis or list of options based on expenditure and outcome? |

8. Validate and refine business case |

Review and test your business case against best practice and identify what else it needs. |

9. Deliver the business case with maximum impact |

Do you have a champion to use in the organisation? Remember you may need to deliver it again. |

10. Share an edited business case |

Remove confidential material and share online so others can benefit from your work |

For a generic digital preservation business case template and more information, see the Digital Preservation Business Case Toolkit

Benefits

Benefits are associated with costs and also with risks (see Risk and change management). If risks are mitigated these become a type of benefit. The purpose of the acquisition of any digital material is that it is used. The uses to which digital material is put represents a benefit to those users. If an organisation needs to understand costs associated with digital materials then it must also understand benefits. Benefits can be used to justify costs through the development of business plans.

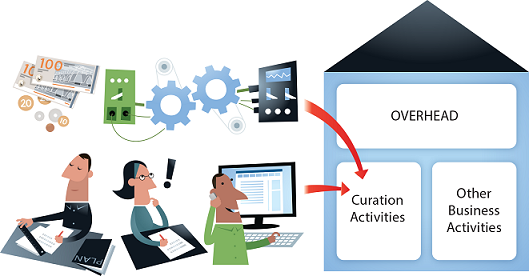

Measuring benefits is often quite challenging, especially when these benefits do not easily lend themselves to expression in quantitative terms. Often a mixture of approaches will be required to analyse both qualitative and quantitative outcomes and present the differences made. To assist institutions, the Keeping Research Data Safe project created a KRDS Benefits Framework and a Benefits Analysis Toolkit (KRDS, 2011). These aim to help institutions identify the full scope of benefits from management and preservation of research data and to present them in a succinct way to a range of different stakeholders (e.g. when developing business cases or advocacy). The toolkit is also easily applicable to the benefits of digital preservation to other classes of digital materials.

The KRDS Benefits Framework uses three dimensions to illuminate the benefits investments potentially generate. These dimensions serve as a high-level framework within which thinking about benefits can be organised and then sharpened into more focused value propositions using the Toolkit. It helps you identify what changes you are trying to deliver, what are the outcomes, who benefits, and how long it will take to realise those benefits.

Costs

A business case will normally look at not just the establishment cost for the digital preservation solution, but the all-in cost, including project/program management costs and other activities being undertaken to support implementation such as training and publicity. However digital preservation costs are often the most critical element.

Why understand digital preservation costs?

These are a few reasons why an organisation might want to estimate digital preservation costs:

- Planning and budgeting to build a new repository from scratch, or to extend an existing one.

- Adding a new digital material to your repository and deciding if you can afford it now or over the long-term.

- Providing a platform for comparison with like organisations and an opportunity to adopt efficiencies that have been identified by others.

- Deciding whether to outsource activities or do it in-house.

- Deciding how much to charge for providing a digital preservation service to clients.

- Understanding where resources are being used or under-utilised and areas where additional allocation of resources might be beneficial.

What is lifecycle cost modelling?

A number of research and development projects have sought to model digital preservation costs across the lifecycle from creation and ingest through to preservation and ultimately access. The large number of projects makes understanding this work, finding which results are most applicable to a particular situation, choosing a model, and putting it into practice a significant challenge. The 4C Project surveyed, analysed and assessed this work and provides guidance on getting the most from it:

- Starting out with curation costs - provides an introduction to the concepts.

- Using cost models - describes how to select a cost model appropriate to your organisation.

- Cost Concept Model and Gateway Specification - provides more detail including a guide to develop a model to your own requirements looking at concepts such as 'risk', 'value', 'quality' and 'sustainability'.

Challenges with cost modelling

Cost modelling has been identified as a particularly challenging activity, with a number of difficult aspects, such as:

- Articulating the drivers or aims for costing digital preservation.

- Digital preservation is a moving target, defined by changing technologies and evolving institutional requirements.

- Level of detail: At a high level, modelling becomes less useful as it typically relates to a cross section of different preservation contexts. Modelling at a low level quickly becomes highly complex, making models difficult to develop, maintain and put into use.

- Organisations are reluctant to share costing data, with which models may be developed and validated.

- Even where costing data has been shared, it is often difficult to map between the different costing models it is associated with.

- Separating out digital preservation costs from other business costs is difficult and sometimes meaningless (example: digitising collections in a way that helps ingest into content into the preservation environment –is this digital preservation or digitisation costs?)

For this reason, modelling digital preservation costs across the lifecycle is an activity that should be approached with caution. Cost modelling will always be an approximation and so you need to decide the amount of time you are willing to put in to gain a less approximate answer.

Managing costs

It is possible to manage costs through careful planning. One way is through good process design. The ways in which digital material is created or acquired, managed and disseminated attract costs. Those costs are at the discretion of the organisation and can be managed. The end to end process from acquisition to dissemination must be designed to ensure that all activities are as efficient as possible. All steps should be designed in such a way as to minimise the need for resources, whilst maximising efficiency. Whilst efficiencies work well at scale, an efficient process doesn't have to be a high volume process. Automation of systematic steps can also save time and deliver effective consistent processes. The initial costs of process design and implementation can be offset by longer term returns.

Impact

Impact is typically the measurement of benefits particularly to the wider public and society undertaken after a business case project has delivered.

For small projects and business cases, impact may be just a simple set of measures such as downloads or number of website requests against which success can be benchmarked easily.

For larger projects and programmes, it may be part of a more thorough evaluation to justify the resources expended. It can include a mixture of quantitative and qualitative measures and will normally be undertaken by external specialists working with staff from the repository. They employ methods from economics and management and information science, for example cost-benefit analysis or contingent valuation, and traditional social science methods such as interviews, surveys and focus groups.

Measurement involves choosing metrics or indicators and requires careful planning and agreement about what to measure and how. Metrics often employ readily countable things such as downloads, or scales metrics that are not truly numeric, such as rating scales or categories of variables. Typically there is a trade-off between what ideally should be measured (e.g. users and use) and proxy measures which are easy to capture and measure (e.g." unique visitors" and web downloads).

Resources

Sustainable Economics for a Digital Planet: Ensuring Long-Term Access to Digital Information

http://brtf.sdsc.edu/biblio/BRTF_Final_Report.pdf

The Blue Ribbon Task Force investigated sustainable digital preservation and access from an economic perspective. This final report, identifies problems intrinsic to all preserved digital materials, and proposes actions that stakeholders can take to meet these challenges to sustainability. It developed action agendas that are targeted to major stakeholder groups and to domain-specific preservation strategies. (2010, 116 pages).

The Value and Impact of Data Sharing and Curation: A synthesis of three recent studies of UK research data centres

This synthesis summarises and reflects on the combined findings from a series of independent investigations into the value and impact of three well established UK research data centres or services (the Economic and Social Data Service, the Archaeology Data Service, and the British Atmospheric Data Centre). The studies adopted a number of approaches to explore the value and impacts of research data services and the data sharing and archiving that they have enabled. Data collection involved focused user and depositor surveys, and data centre financial and operational data (e.g. user registrations, dataset deposits and downloads), supplemented by in-depth interviews. Not all impacts can be captured and quantified; therefore they have used these economic approaches with others, such as the KRDS Benefits Framework, to illustrate wider benefits. (2014, 26 pages).

Jisc Guide: Digitising your collections sustainably

https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/digitising-your-collections-sustainably

Provides a starting point for considering the issues necessary to create and build a business model that will support sustainability of digitisation and digital collections.

4C Project Collaboration to Clarify the Costs of Curation

The European Union funded 4C project aimed to help organisations across Europe to invest more effectively in digital curation and preservation. A series of reports and resources were produced and are available from its outputs and deliverables page. These include the Digital Curation Sustainability Model , an Evaluation of Cost Models and Needs & Gaps Analysis, a Report on Risk, Benefit, Impact and Value, and a Draft Economic Sustainability Reference Model. The evaluation of costs models report evaluates ten available cost models including, KRDS and LIFE. Another major output was the Curation Costs Exchange (CCEx), a community owned platform which helps organisations of any kind assess the costs of curation practices through comparison and analysis. The CCEx aims to provide real information about costs to help make more informed investments in digital curation. The CCEx was launched in 2014 by 4C and is now maintained and governed by the Digital Preservation Coalition (DPC) with help from nestor and The Netherlands Coalition for Digital Preservation (NCDD).

Digital Preservation Business Case Toolkit

http://wiki.dpconline.org/index.php?title=Digital_Preservation_Business_Case_Toolkit

This Toolkit provides an in depth guide to writing a business case that is focused on digital preservation activities. It's targeted at practitioners (and their managers) who are working with digital resources and would like to obtain funds to expand their digital preservation activities. The Toolkit is primarily aimed at those seeking further funds from within their organisation, but could also provide useful information for those writing a bid for project funds from an external funding body. It includes a Step by step guide to building a business case and a Template for building a business case. Created by the Jisc funded SPRUCE Project in 2013 the toolkit wiki is hosted by the DPC.

Keeping Research Data Safe (KRDS) Benefits Toolkit

Keeping Research Data Safe (KRDS) is a series of cost/benefit studies, tools and methodologies that focus on the challenges of assessing costs and benefits of curation and preservation of research data. Although focussing on research data, the tools are easily customised to apply to other areas of digital preservation. Available outputs include a KRDS Factsheet, a KRDS User Guide, a KRDS Activity Cost Model, and a KRDS Benefits Analysis Toolkit as well as supplementary materials and reports. The KRDS projects between 2008 and 2011 were funded by Jisc.

20 Cost Questions for Digital Preservation

http://www.metaarchive.org/public/publishing/ma_20costquestions_final.pdf?thumblink

The MetaArchive Cooperative has produced a set of 20 questions to "assist institutions with their comparative analysis of various digital preservation solutions". This work marks a move away from the development of detailed predictive costing models towards a more general approach that seeks to identify and understand key cost drivers rather than the actual costs themselves.

DSHR's Blog

http://blog.dshr.org/search/label/storage%20costs

http://blog.dshr.org/search/label/cloud%20economics

David Rosenthal is a frequent blogger on the topic of storage costs, often considering the impact of the evolution of storage technology on preservation costs and on cloud storage.

A Digital Asset Sustainability and Preservation Cost Bibliography

A bibliography that "ranges broadly, from articles on "contingent valuation," "ecosystem valuation" and the general "costs" of knowledge, to those that directly address the cost issues associated with digital preservation and stewardship".

Digital Preservation and Data Curation Costing and Cost Modelling

http://wiki.opf-labs.org/display/CDP/Home

A list of digital preservation cost models and cost modelling initiatives.

![]()

The Cost of Inaction Calculator Rationale

https://coi.weareavp.com/rationale

This is a great information video from AVPreserv on the cost of inaction and the business case rationale for digital preservation. It is focussed on Audio-Visual material but it worth listening to and thinking laterally about the underlying rationale whatever type of digital material you hold. (8mins 41sec)

Case studies

![]()

KRDS Benefits Toolkit case studies

There are 4 case studies providing worked examples of completed worksheets from project partners as follows:

Archaeology

The background to this case study is provided in the Archaeology Data Service (ADS) dissemination workshop presentation. Worked examples are available of the ADS Benefits Framework Worksheet (PDF) and the ADS Value-chain and Impact Worksheet (Excel 97-2003).

Health: Population Cohort Studies

http://www.ukoln.ac.uk/events/i2s2-krds/presentations/dipak-kalra-krds-benefits-2011-07.ppt

The background to this case study is provided in the Medical Research Council Cohort Studies dissemination workshop presentation. A worked example is available of the Cohort Studies Value-chain and Impact Worksheet (Excel 97-2003).

Research Data Citation: SageCite

http://www.ukoln.ac.uk/events/i2s2-krds/presentations/monica-duke-krds-sagecite-benefits-2011-07.ppt

The background to this case study is provided in the SageCite dissemination workshop presentation. A worked example is available of the SageCite Benefits Framework Worksheet (PDF).

Social Sciences: UK Data Archive (UKDA)

http://www.ukoln.ac.uk/events/i2s2-krds/presentations/matthew-woollard-krds-benefits-2011-07.ppt

The background to this case study is provided in the UKDA dissemination workshop presentation. A worked example is available of the UKDA Benefits Impact Worksheet (PDF).

Digital Preservation Business Case Toolkit

There are four case studies as follows sourced from activities conducted as part of SPRUCE Project Awards:

Bishopsgate library case study

http://wiki.dpconline.org/index.php?title=Bishopsgate_library_case_study

A collections audit and business case focused on taking the first steps of digital preservation.

Institute of education case study

http://wiki.dpconline.org/index.php?title=Institute_of_education_case_study

A review of approach and generation of a business case for digital administrative record keeping.

Northumberland estates case study

http://wiki.dpconline.org/index.php?title=Northumberland_estates_case_study

Assessment of digital repository solutions and an associated business case for digital preservation.

Lovebytes case study

http://wiki.dpconline.org/index.php?title=Lovebytes_case_study

A trial of media stabilisation and content preservation along with a business case to move to a production status.

References

Keeping Research Data Safe (KRDS), 2011. Digital Preservation Benefits Analysis Toolkit. Available: http://beagrie.com/krds-i2s2.php

Standards and best practice

Illustration by Jørgen Stamp digitalbevaring.dk CC BY 2.5 Denmark

Introduction

The use and development of reliable standards has long been a cornerstone of the information industry. They facilitate the access, discovery and sharing of digital resources, as well as their long-term preservation. There are both generic standards applicable to all sectors that can support digital preservation, and industry-specific standards that may need to be adhered to. Using standards that are relevant to the digital institutional environment helps with organisational compliance and interoperability between diverse systems within and beyond the sector. Adherence to standards also enables organisations to be audited and certified.

Operational standards

There are a number of standards which can help with the development of an operational model for digital preservation.

Taking custodial control of digital materials requires a set of procedures to govern their transfer into a digital preservation environment. This can include identifying and quantifying the materials to be transferred, assessing the costs of preserving them and identifying the requirements for future authentication and confidentiality. ISO 20652: Space Data and Information Transfer Systems - Producer-Archive Interface - Methodology Abstract Standard (ISO, 2006) is an international standard that provides a methodological framework for developing procedures for the formal transfer of digital materials from the creator into the digital preservation environment. Objectives, actions and the expected results are identified for four phases - initial negotiations with the creator (Preliminary Phase), defining requirements (Formal Definition Phase), the transfer of digital materials to the digital preservation environment (Transfer Phase) and ensuring the digital materials and their accompanying metadata conform to what was agreed (Validation Phase).

ISO 14721:2012 Space Data and Information Transfer Systems - Open Archival Information System - Reference Model (OAIS) (ISO, 2012b) provides a systematic framework for understanding and implementing the archival concepts needed for long-term digital information preservation and access, and for describing and comparing architectures and operations of existing and future archives. It describes roles, processes and methods for long-term preservation. Developed by the Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems (CCSDS) OAIS was first published in 1999 and has had an influence upon many digital preservation developments since the early 2000s. A useful introductory guide to the standard is available as a DPC Technology Watch Report (Lavoie, 2014).

An OAIS is ‘an archive, consisting of an organization of people and systems that has accepted the responsibility to preserve information and make it available for a defined ‘Designated Community’. An ‘OAIS archive’ could be distinguished from other uses of the term ‘archive’ by the way that it accepts and responds to a series of specific responsibilities. OAIS defines these responsibilities as:

- Negotiate for and accept appropriate information from information producers;

- Obtain sufficient control of the information in order to meet long-term preservation objectives;

- Determine the scope of the archive’s user community;

- Ensure that the preserved information is independently understandable to the user community, in the sense that the information can be understood by users without the assistance of the information producer;

- Follow documented policies and procedures to ensure the information is preserved against all reasonable contingencies, and that there are no ad hoc deletions.

- Make the preserved information available to the user community, and enable dissemination of authenticated copies of the preserved information in its original form, or in a form traceable to the original. (Lavoie, 2014)

OAIS also defines the information model that needs to be adopted. This includes not only the digital material but also any metadata used to describe or manage the material and any other supporting information called Representation Information.

The OAIS functional model is widely used to establish workflows and technical implementations. It defines a broad range of digital preservation functions including ingest, access, archival storage, preservation planning, data management and administration. These provide a common set of concepts and definitions that can assist discussion across sectors and professional groups and facilitate the specification of archives and digital preservation systems.

OAIS provides a high level framework and a useful shared language for digital preservation but for many years the concept of ‘OAIS conformance/compliance’ remained hard to pin down. Though the term was frequently used in the years immediately following the publication of the standard, it relied on the ability to measure up to just six mandatory but high level responsibilities. A more detailed discussion about ‘OAIS compliance’ can be found in the Technology Watch Report.

ISO/TR 18492:2005 Long-term preservation of electronic document-based information (ISO/TR, 2005) provides a practical methodology for the continued preservation and retrieval of authentic electronic document-based information, which includes technology-neutral guidance on media renewal, migration, quality, security and environmental control. The guidance is developed to ensure authenticity of records beyond the lifetime of original information keeping systems.

ISO 15489:2001 Information and documentation -- Records management (ISO, 2001) can also be a useful standard for defining the roles, processes and methods for a digital preservation implementation where the focus is the long-term management of records. This standard outlines a framework of best practice for managing business records to ensure that they are curated and documented throughout their lifecycle while remaining authoritative and accessible.

ISO 16175:2011 Principles and functional requirements for records in electronic office environments (ISO, 2011) relates to electronic document and records management systems as well as enterprise content management systems. While it does not include specific requirements for digital preservation, it does acknowledge the need to maintain records over time and that format obsolescence issues need to be considered in the specification of these electronic systems.

There are international standards that are generic to good business management that may also be relevant in the digital preservation domain.

- Certification against ISO 9001 Quality management systems (ISO, 2015) demonstrates an organisation’s ability to provide and improve consistent products and services.

- Certification against ISO/IEC 27001 Information technology -- Security techniques -- Information security management systems (ISO/IEC, 2013) demonstrates that digital materials are securely managed ensuring their authenticity, reliability and usability.

- ISO/IEC 15408 The Common Criteria for Information Technology Security Evaluation (ISO/IEC, 2009) provides a standardised framework for specifying functional and assurance requirements for IT security and a rigorous evaluation of these.

There are a number of routes through which a digital preservation implementation can be certified. These range from light touch peer review certification methods such as the Data Seal of Approval, through the more extensive internal methods of DIN 31644 Information and documentation - Criteria for trustworthy digital archives (DIN, 2012), to the comprehensive international standard ISO 16363:2012 Audit and certification of trustworthy digital repositories (ISO, 2012a) (see Audit and certification).

Technical standards

There are specific advantages to using standards for the technical aspects of a digital preservation programme, primarily in relation to metadata and file formats.

In conjunction with relevant descriptive metadata standards, PREMIS and METS are de facto standards which will enhance a digital preservation programme. PREMIS (PREservation Metadata: Implementation Strategies) is a standard hosted by the Library of Congress and first published in 2005. The data dictionary and supporting tools have been specifically developed to support the preservation of digital material. METS (Metadata Encoding and Transmission Standard) is an XML encoding standard which enables digital materials to be packaged with archival information (see Metadata and documentation).

There are also standards relating to file formats. Choosing file formats that are non-proprietary and based on open format standards gives an organisation a good basis for a digital preservation programme. ISO/IEC 26300-1:2015 Open Document Format for Office Applications (ISO/IEC, 2015) provides an XML schema for the preservation of widely used documents such as text documents, spreadsheets, presentations. ISO 19005 Electronic document file format for long-term preservation (ISO, 2005) prescribes elements of valid PDF/A which ensures that they are self-contained and display consistently across different devices. Aspects of JPEG-2000 and TIFF are also covered by ISO standards. (see File formats and standards).

Barriers to using standards

A standards based approach to digital preservation is important, but there are also factors which inhibit their use as a digital preservation strategy:

- The pace of change is so rapid that standards which have reached the stage of being formally endorsed - a process which usually takes years - will inevitably lag behind developments and may even be superseded.

- Competitive pressures between suppliers encourage the development of proprietary extensions to, or implementations of standards which can dilute the advantages of consistency and interoperability for preservation.

- The standards themselves adapt and change to new technological environments, leading to a number of variations of the original standard which may or may not be interoperable in the long-term even if they are backwards compatible in the short-term.

- Standards can be intimidating to read and resource intensive to implement.

- In such a changeable and highly distributed environment, it is impossible to be completely prescriptive.

These factors mean that standards will need to be seen as part of a suite of preservation strategies rather than the key strategy itself. The digital environment is not inclined to be constrained by rigid rules and a digital preservation programme can often be a blend of standards and best practice that is sufficiently flexible and adapted to suit the needs of the organisation, its circumstances and the digital materials being managed.

Standards, best practice and good practice

In recent years best practice guidance and case studies have been published by national archives, national libraries and other cultural organisations. Digital preservation is also a topic well discussed on blogs and social media which can often provide real time information in relation to theory and practice from around the world. Papers at conferences such as iPRES, the International Digital Curation Conference (IDCC) and the Preservation and Archiving Special Interest Group (PASIG) can be a useful source of up to date thinking from academics and practitioners in digital preservation.

Standards should be understood as a formal description and recognition of what a community of experts might term best practice. Standards, and the best practice from which they derive can be intimidating and there is a risk for those starting in digital preservation that the ‘best becomes the enemy of the good’. So in adopting or recommending standards it should always be understood that some action is almost always better than no action. Digital preservation is a messy business which throws up unexpected challenges. So it is almost always the case that a poorly implemented standard is preferable to waiting for perfection.

Sector specific requirements

Specific industries have become active in the development of preservation standards, and particular types of content and use cases have emerged that overlap and extend a number of standards. There is considerable benefit in digital preservation standards being embedded in sector-specific standards since this will greatly assist their adoption, although this may present a challenge to coordination of activities. Three examples are given below:

- Audio visual materials present a special case for digital preservation (see Moving pictures and sounds). Recommendations for audio recordings and video recordings exist under the auspices of the International Association of Sound and Audio-visual Archives (such as IASA- TC04, 2009), while a range of industry bodies and content holders including the BBC, RAI, ORF and INA have formed the PrestoCentre to progress research and development of preservation standards in this field. https://www.prestocentre.org/

- The aerospace industry has particular requirements in product lifecycle management and information exchange which have given rise to a series of industry wide initiatives to standardise approaches to aligning and sharing CAD drawings for engineering. The membership body PROSTEP created the ISO 10303 ‘Standard for Exchange of Product Model Data’ which has developed into the LOTAR standard (http://www.lotar-international.org/lotar-standard/overview-on-parts.html). LOTAR is not incompatible with OAIS, but because it fits within a data exchange protocol important to the industry, aerospace engineers are more likely to encounter LOTAR than OAIS

- .The Storage Network Industry Association has also begun to make progress on the development of a series of standards. A SNIA working group on long-term data retention has responsibility for both physical and logical preservation, and the creation of reference architectures, services and interfaces for preservation. In addition, a working group on Cloud Storage is likely to become particularly influential in relation to preservation. Cloud architectures change how organizations view repositories and how they access services to manage them. For example, it is unclear how one would measure the success of a ‘trusted digital repository’ that was based in a cloud provider.

Resources

![]()

Seeing Standards; A visualisation of the metadata universe

http://jennriley.com/metadatamap/

The sheer number of metadata standards in the cultural heritage sector is overwhelming, and their inter-relationships further complicate the situation. This visual map of the metadata landscape is intended to assist planners with the selection and implementation of metadata standards. Each of the 105 standards listed here is evaluated on its strength of application to defined categories in each of four axes: community, domain, function, and purpose. (2010, 1 page).

Dlib Magazine

Dlib Magazine publishes on a regular basis a wide range of papers and case studies on the practical implementation of digital preservation standards and best practice. ![]()

Core Trust Seal

https://www.coretrustseal.org/

PREMIS

http://www.loc.gov/standards/premis/

Library of Congress, 2015

The Digital Curation Centre

The Digital Curation Centre makes available research and case studies in relation to the preservation of research data. Iit also publishes recordings of its annual international digital curation conference proceedings.

The Signal

http://blogs.loc.gov/digitalpreservation/

The Signal is a digital preservation blog published by the Library of Congress

IPRES

http://www.ipres-conference.org/

IPRES, the International Conference on Digital Preservation publishes a website and proceedings from their annual event which looks at different themes within the digital preservation landscape,

The Digital Preservation Coalition Wiki

http://wiki.dpconline.org/index.php?title=Main_Page

The Digital Preservation Coalition Wiki provides a collaborative space for users of OAIS, the British Library’s file format assessments as well as other resources.

Digital Preservation Matters

http://preservationmatters.blogspot.co.uk/

The Digital Preservation Matters blog is a personal account of experiences from working with Digital Preservation

References

DIN, 2012. DIN 31644 Information and documentation - Criteria for trustworthy digital archives. Available: http://data-archive.ac.uk/curate/trusted-digital-repositories/standards-of-trust?index=3

IASA-TC04, 2009. Guidelines in the Production and Preservation of Digital Audio Objects: standards, recommended practices, and strategies: 2nd edition, edited by Kevin Bradley. Available: http://www.iasa-web.org/tc04/publication-information

ISO, 2001. ISO 15489:2001 Information and documentation -- Records management. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=31908

ISO, 2005. ISO 19005-1:2005. Document management -- Electronic document file format for long-term preservation. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=38920

ISO, 2006. ISO 20652:2006 Space Data and Information Transfer Systems - Producer-Archive Interface - Methodology Abstract Standard. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=39577

ISO, 2011. ISO 16175:2011 Principles and functional requirements for records in electronic office environments. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=55791

ISO, 2012a. ISO 16363:2012 Audit and certification of trustworthy digital repositories. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=56510

ISO, 2012b. ISO 14721:2012 Space Data and Information Transfer Systems - Open Archival Information System (OAIS) - Reference Model. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=57284

ISO, 2015. ISO 9001:2015 Quality management systems. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=62085

ISO/IEC, 2009. ISO/IEC 15408:2009 The Common Criteria for Information Technology Security Evaluation. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=50341

ISO/IEC, 2013. ISO/IEC 27001:2013 Information technology -- Security techniques -- Information security management systems. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=54534

ISO/IEC, 2015. ISO/IEC 26300-1:2015 Information technology -- Open Document Format for Office Applications (OpenDocument) v1.2 -- Part 1: OpenDocument Schema. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available:http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_ics/catalogue_detail_ics.htm?csnumber=66363

ISO/TR, 2005. ISO/TR 18492:2005 Long-term preservation of electronic document-based information. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=38716

Lavoie, B., 2014. The Open Archival Information System (OAIS) Reference Model: Introductory Guide (2nd Edition). DPC Technology Watch Report 14-02. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.7207/twr14-02

Library of Congress, 2015. METS Metadata Encoding and Transmission Standard. Available: http://www.loc.gov/standards/mets/

Staff training and development

Illustration by Jørgen Stamp digitalbevaring.dk CC BY 2.5 Denmark

Introduction

A well-skilled and effective workforce can be an organisation's greatest asset, yet due care and attention is not always given to providing adequate training and development, and encouraging its uptake. Additionally, developing and maintaining a digital preservation programme can seem daunting in many ways and, in particular, this is often due to a perceived staff skills gap. This may be because the work environment is characterised by:

- Rapid and ongoing change.

- Blurring of boundaries within and between institutions.

- Uncertainty in terms of the ability to confidently predict future trends and requirements.

- Unclear and/or changing roles and responsibilities.

- Increased emphasis on collaboration and teamwork.

- Increased emphasis on accountability.

Carefully designed staff training and continuous professional development (CPD) activities can play a key role in successfully making the transition from the traditional model of libraries and archives to the digital or hybrid model. Intelligent training and development can do much to boost confidence and ability in staff members, and minimise anxiety about the changing nature of work in preservation-performing institutions. A thoughtful approach to training and development (as opposed to just "sending people on courses") is likely to make a significant difference by:

- Helping staff to exploit technology effectively and improve the overall quality of service.

- Enhancing the individual level of job satisfaction and commitment, leading to improved staff retention.

- Improving the strategic outlook for the organisation as a whole.

Organisations should take a strategic approach to training and development, considering carefully the skills that are required, as well as new and developing roles and responsibilities. The issue should be clearly addressed in all relevant digital preservation policy, strategy and planning, and budget for advocacy and skills development activities should be an integral part of planning for digital preservation work.

A Broad Range of Skills

Successful digital preservation work requires a broad range of skills, from those specific to the area such as knowledge of metadata standards and audit frameworks, to more general skills such a project planning and risk management. Therefore, ensuring all staff members have adequate digital preservation-specific skills for their part of the process is only one aspect of the preparation required for equipping them to maximise the potential of digital technology. It is highly unlikely that one individual will ever possess all of the skills required to undertake the full range of digital preservation activities, so collaboration will remain key to success. Skilful training can enhance individual skills and competences but can also enhance understanding of the other skills and competences required for a successful collaborative project.

A number of different initiatives have endeavoured to clarify the skills and competencies required for digital preservation work and potential roles involved for staff at different levels of seniority:

DPOE

The Library of Congress's Digital Preservation Outreach and Education programme (DPOE) has defined three levels of staff roles (or career stages) within their model for digital preservation training. These are:

- Executive - those in senior institutional management roles.

- Managerial - those managing digital preservation programmes and service.

- Practical - practitioners working hands-on with digital materials and preservation solutions.

DigCurV

The DigCurV project adapted the DPOE's three level model for their work in defining the core competencies required for digital preservation work. The DigCurV project examined a number of issues relating to digital curation and preservation training, skills and development, producing a variety of useful resources including a database of available training opportunities and a curriculum framework. Describing the core competencies required at each of the three levels in the DPOE model through a set of 'lenses', the DigCurV curriculum framework provides an excellent resource for those looking to identify the full range of skills and competencies required for digital curation and preservation. Specifically, the DigCurV curriculum framework can help users to describe and compare training courses, to develop new training resources and to map the skills and knowledge of an individual or team to identify any existing skills gaps.

Each lens is split into four sections covering

- Knowledge and Intellectual Abilities

- Personal Qualities

- Professional Conduct

- Management and Quality Assurance

Each then contain further sub-sections that list general statements about individual competencies. The statements are designed to be generic so have a broad applicability, although specific examples of particular standards or tools relating to the competencies are available via the version on the DigCurV website.

DigCCurr

The DigCCurr (Preserving Access to Our Digital Future: Building an International Digital Curation Curriculum) project has produced a 6-dimensional matrix for identifying and organizing the material to be covered in a digital curation curriculum. This Matrix of Digital Curation Knowledge and Competencies is an alternative approach that may be particularly useful for smaller organisations.

Roles and Responsibilities for Training and Development

Roles and responsibilities need to be clearly defined. The success of training and development programmes will be affected by the degree to which various roles and responsibilities mesh. It is essential that each of the stakeholders in the process fully appreciate their roles and actively participate in the process. Listed below is a guide to the various responsibilities that may be required of different stakeholders to ensure the creation and deployment of a successful and comprehensive training and development programme.

Stakeholder roles and responsibilities |

Roles and Responsibilities of the Institution

|

Roles and Responsibilities of Professional Associations

|

Roles and Responsibilities of the Individual

|

Undertaking a Skills Audit

A useful starting point for any organisation is to conduct a skills audit tailored to the needs of the specific institution. The process will help identify any skills gaps that exist and allow informed decisions to be made about training and development, as well as potentially highlighting additional roles that may require new staff or new responsibilities (and new job descriptions) for those already in post. Evidence from the skills audit can then be used to build a business case for any additional resources that may be required. In addition to being an excellent starting point for improving staff development it may also be useful to incorporate elements of the process into regular staff professional development and review processes.

The DigCurV curriculum framework or the Matrix of Digital Curation Knowledge and Competencies can provide a useful tool when carrying out a skills audit, in this case as a resource for benchmarking. It will be necessary to tailor the audit to the staff development practices and processes of individual organisations but the following steps may be considered:

- Identify all roles within the organisation with digital preservation responsibilities. Examining workflows can help in this process and mapping these to models such as the OAIS Reference Model or the Digital Curation Centre Curation Lifecycle Model.

- Map roles to the relevant lenses of the DigCurV framework.

- Work with role holders to map skills to the relevant lens. This can be done variety of ways including self-assessment and as a group activity. It may also be useful to mark on a scale.

- Analyse results to identify gaps, training requirements and additional roles required.

Training and Development Options

A lack of established training and development opportunities was previously a considerable barrier to those wishing to learn more about digital preservation. While those at more advanced levels in their development may still struggle to find appropriate opportunities, there are now a number of established courses available to those at a beginner and intermediate level from short courses to full degree programmes including a variety of training opportunities addressing specific specialist areas of interest. A greater barrier is now the time and expense involved in attending face-to-face training, but increasingly more online and distance learning options are being made available so this impediment will also decrease.

Digital preservation courses have also previously suffered from criticism relating to an emphasis on theory rather than practice. This too is changing with more practical exercises and tool demos being incorporated into training. Digital preservation also remains a discipline where as much, if not more, can be learnt by doing, so peer to peer learning and a willingness to just get your hands dirty can often produce the best results. Information sharing and short staff exchanges with similar organisations can provide a particularly effect method for staff development and learning.

Resources

![]()

2014 DPOE Training Needs Assessment Survey

http://www.digitalpreservation.gov/education/2014_Survey_Report-Final.pdf

An analysis of the state of digital preservation practice and the capacity to preserve digital content within organisations in the United States with the aim of establishing training gaps and needs. (13 pages).

![]()

DigCurV, A Curriculum Framework for Digital Curation

The DigCurV Curriculum Framework offers a means to identify, evaluate, and plan training to meet the skill requirements of staff engaged in digital curation. The DigCurV team undertook multi-national research in the Cultural Heritage sector to understand the skills used by those working in digital curation, and those sought by employers in this sector. The framework defines separate skills lenses to match the specific needs of three distinct audiences; Executives, Managers, and Practitioners.

- The skills defined under the Executive Lens enable a digital curation professional to maintain a strategic view .

- The skills defined under the Manager Lens enable a professional to plan and monitor execution of digital curation projects, to recruit and support project teams, and to liaise with a range of internal and external contacts within the cultural heritage sector.

- The skills defined under the Practitioner Lens enable a professional to plan and execute a variety of technical tasks, both individually and as part of a multi-disciplinary team.

Matrix of Digital Curation Knowledge and Competencies

http://ils.unc.edu/digccurr/digccurr-matrix.html

The DigCCurr (Preserving Access to Our Digital Future: Building an International Digital Curation Curriculum) project has produced a 6-dimensional matrix for identifying and organizing the material to be covered in a digital curation curriculum.

Digital Preservation Outreach and Education

http://www.digitalpreservation.gov/education/curriculum.html

The Library of Congress's 'baseline' digital preservation training programme for archives and collections management staff. The full course is delivered to archives and other digital preservation professionals in a 'train the trainer' approach, in order to support further dissemination to colleagues. The overview videos are available online.

DPC Training

https://www.dpconline.org/knowledge-base/training

A key role for the DPC is to empower and develop its members' workforces. The DPC addresses this issue by facilitating training and support activities and creating practitioner-focused material and events throughout each year. These include The DPC Leadership Programme, The Digital Preservation Roadshow, and The Member Briefing Days and Invitational Events.

Digital Preservation Training Programme (DPTP)

A range of UK based digital preservation training courses. Scheduled DPTP courses run over 2 days or 3 days and take place regularly throughout the year.

Digital Preservation Management: Implementing Short-Term Strategies for Long-Term Solutions

An excellent free online tutorial that introduces you to the basic tenets of digital preservation. It is particularly geared toward librarians, archivists, curators, managers, and technical specialists. It includes definitions, key concepts, practical advice, exercises, and up-to-date references. The tutorial is available in English, French, and Italian.

UK University post-graduate degree courses

http://www.dpconline.org/knowledge-base/training

The DPC maintains a list that will be helpful to anyone looking at post- graduate degrees with a focus on digital preservation. It includes University on campus and distance learning options. Some universities also offer individual credit bearing modules in relevant digital preservation topics.

Education and Training in Audio-visual Archiving and Preservation

http://www.arsc-audio.org/etresources.html

Training opportunities in Australia, Europe and the USA for those working with sound and moving image material.

Connecting to Collections: Caring for Audio-visual Material

http://www.connectingtocollections.org/av/

Self-paced course including recorded webinars, hand-outs, slideshows and suggested further reading for the individual student working with audio-visual material. It covers basic principles, a history of formats and their preservation challenges, format identification, access issues and an overview of existing models and standards. It is written in English by a team of US-based archivists, conservators and digital preservation experts.

![]()

How the DPC makes a difference to your staff

Short interviews with 5 candidates who were sponsored by the Digital Preservation Coalition to attend the Digital Futures Academy in London in March 2012. They reflect on their experience and how joining the DPC has benefitted their institutions. (2 mins 40 secs)

Risk and change management

Illustration by Jørgen Stamp digitalbevaring.dk CC BY 2.5 Denmark

Introduction

Digital preservation is not simply about risks. It also creates opportunities and by protecting digital materials it means that new or extended value can be derived from them. It can be easy to become overwhelmed with risks, so It is worth being explicit early in the process about what opportunities are being protected or created. There are many things that put your digital resources at risk including changes to your organisation or technology. If not managed, these risks will have a significant impact on your ability to carry out your digital preservation activities, wider business functions, or comply with legislation.

To manage digital preservation, you must understand your organisation's specific issues and risks. You can do this by undertaking a risk and opportunities assessment. The assessment will highlight specific risks to the continuity of your digital resources, and opportunities that can be realised from mitigating these risks.

Risk management

Experience shows that the risks facing digital resources are subtle and varied. They include, but are not limited to the following:

|

|

Data loss is likely to have a variety of real world consequences depending on context. In the context of a court case, for example, the authenticity of a document could become a significant legal issue; whereas for highly structured research data the chain of custody may matter less than access to explanatory context that enables the reproducibility of an experiment. In many contexts it may be technically possible to recover digital collections but where an organisation simply doesn't have the wherewithal or skills necessary to restore a data set, then practical obsolescence and data loss can result. This is likely to become more of a reality as the number and complexity of digital collections expand.

The risks to digital content usually matter because of their consequences in the real world. Again this depends on the context but the following can occur:

- Loss of reputation.

- Inadequate resources for a critical task.

- Inability to support users in their activities.

- Failure to discharge legal or regulatory function.

- Inability to exploit and reuse data.

- Loss of identity and corporate memory.

- Cost of recreation and recovery.

Risks are typically prioritised by calculating a 'risk score' based on likelihood, impact and imminence: an imminent risk with a strong probability and a large negative impact needs prompt action. Depending on the nature of the risk this might include taking steps to reduce the likelihood of a risk emerging, reducing the impact if a risk does occur, or buying time for mitigation steps to be implemented.

Risk assessment is an ongoing process that can be developed and expanded through time. It can help bring together different stakeholders and, because risk management is understood by senior management it can also help to make the case for investment. Even an elementary risk assessment will highlight priorities for anyone getting started in digital preservation.

Finally it is worth noting that digital preservation is distinctive in being long-term and most risk methodologies are typically focussed on the short-term. For digital preservation, you need to be aware that over the long term improbable events will become more likely and special attention should be paid to those with significant consequences.

Business continuity planning

Rationale

'Interested parties and stakeholders require that organizations proactively prepare for potential incidents and disruptions in order to avoid suspension of critical operations and services, or if operations and services are disrupted, that they resume operations and services as rapidly as required by those who depend on them.' (ISO/PAS 22399:2007).

Business Continuity planning and practice is well-established within the IT profession and is not dealt with in detail in the Handbook. However it is an important component of ensuring bit preservation and makes a significant contribution to digital preservation through this. There is a series of webinars on business continuity and digital preservation from the TIMBUS project (see Resources).

The development and use of a business continuity plan based on sound principles, endorsed by senior management, and activated by trained staff will greatly reduce the likelihood and severity of impact of disasters and incidents.

One model is the plan developed by the Data Archive, and described in the DPC Case note on Business Continuity. Organisations may also wish to consider use of cloud services (see Cloud services) as part of their planning.

Requirements

- Develop a business continuity plan.

- Ensure all relevant staff are trained in business continuity procedures.

- Create copies of data resources at the time of their transfer to the institution.

- Store copies on industry standard or other approved contemporary media.

- Store copies on and off site. Off-site copies should be stored at a safe distance from on-site copies to ensure they are unaffected by any natural or man-made disaster affecting the on-site copies.

- Consider data and skills as assets and compile registers of them.

- Ensure roles and responsibilities are identified and maintained.

Resources

![]()

ISO/PAS 22399:2007 Societal security - Guideline for incident preparedness and operational continuity management

http://www.iso.org/iso/catalogue_detail?csnumber=50295

This standard provides general guidance for any organization to develop its own specific performance criteria for incident preparedness and operational continuity, and design an appropriate management system.

ISO/IEC 27001:2013 Information technology -- Security techniques -- Information security management systems -- Requirements

http://www.iso.org/iso/catalogue_detail?csnumber=54534

This standard specifies the requirements for establishing, implementing, maintaining and continually improving an information security management system. The requirements are generic and are intended to be applicable to all organizations.

![]()

Disaster Preparedness for Digital Content

http://dpworkshop.org/workshops/management-tools/disaster-preparedness

A Digital Preservation Management workshop webpage that links a set of 4 suggested documents (disaster plan policy, communications plan, training plan, roles and responsibilities). Cumulatively they provide comprehensive documentation and are updated to reflect current practice for disaster preparedness.

National Archives Risk assessment tools

The National Archives provide two excel format self-assessment tools that link to its digital continuity guidance and framework of solutions and services.

The Self-assessment tool (0.4 Mb) divides the risk assessment into three sections: Understanding digital continuity and roles and responsibilities; Information requirements and technical dependencies, and Management

The Information asset risk assessment tool (0.26 Mb) helps you identify risks to the continuity of any specific digital information asset and identifies where continuity has already been lost. It makes recommendations on maintaining or restoring continuity to help you develop a digital continuity action plan.

DRAMBORA (Digital Repository Audit Method Based on Risk Assessment) Toolkit

This is an online toolkit for a digital repository audit. The toolkit guides users through the audit process, from defining the purpose and scope of the audit to identifying and addressing risks to the repository. DRAMBORA provides a list of over 80 examples of potential risks to digital repositories, framed in terms of possible consequences.

SPOT

http://www.dlib.org/dlib/september12/vermaaten/09vermaaten.html

The SPOT (Simple Property-Oriented Threat) provides a simple model for risk assessment, focused on safeguarding against threats to six properties of digital objects fundamental to their preservation: availability, identity, persistence, renderability, understandability, and authenticity. The model discusses threats in terms of their potential impacts on these properties, providing several example outcomes for each. The article describing the model also included a useful comparison of other digital preservation threat models.

![]()

Managing digital continuity guidance from The National Archives

Includes a helpful risk assessment with many correlations to risk management strategies for Business Continuity Planning.

Assess and manage risks to digital continuity

The National Archives have built a self-assessment tool for the wider public sector that links to its digital continuity guidance and framework of solutions and services.

Assess risks to digital continuity factsheet

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/information-management/assess-dc-risks-factsheet.pdf

(2 pages)

Risk assessment handbook

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/information-management/Risk-Assessment-Handbook.pdf

(35 pages)

The Atlas of Digital Damages

https://www.flickr.com/groups/2121762@N23/

This is a staging area for collecting visual examples of digital preservation challenges, failed renderings, encoding damage, corrupt data, and visual evidence documenting #FAILs of any stripe. You can contribute just an image, tell the story behind the image, or share the original file (or set of files), so that tool developers can learn from digital damage and test out their code with it.

![]()

TIMBUS project: Business Continuity Management 1 - Intro, Life Cycle, Planning, Scope

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=25EhtuE3XkE

1 of 4 Business Continuity Management and the Digital Preservation of Processes webinars from the EU-funded Timbus project. This introduction is probably the most accessible for novices (released 2013. 13 mins).

Case studies

![]()

DPC case note: Business continuity procedures – UK Data Archive, University of Essex

The Data Archive is the UK national data centre for the Social Sciences funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). The Archive holds certification to ISO 27001, the international standard for information security, which requires information security continuity to be embedded in an organisation's business continuity management systems. The digital storage system at the Data Archive is based, for security purposes, on segregated and distributed storage and access. Business continuity at the Data Archive is based around the resilience provided by creating multiple copies of the data and specified recovery procedures, alongside pre-emptive failure prevention. Each file from any dataset has at minimum three copies. The Archive also creates a read only archival copy of each study and any update as it is made available on the system.

References

ISO, 2007. ISO/PAS 22399:2007. Societal security - Guideline for incident preparedness and operational continuity management. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/catalogue_detail?csnumber=50295

Legal Compliance

Illustration by Jørgen Stamp digitalbevaring.dk CC BY 2.5 Denmark

Introduction

The information provided in this section is intended solely as general guidance on the legal issues arising from various aspects of digital archiving and preservation and is not legal advice. It does not attempt to provide guidance on general legal issues which impact on the operations of libraries, archives and other repositories, as these are covered in a number of other reference works. It is written from a UK perspective and legislation in this area will vary from country to country. Although it principally covers UK and European legal issues, many of the topics will also apply in general terms to other jurisdictions.

An adviser–client relationship is not created by the information provided. If you need more details pertaining to your rights and obligations, or legal advice about what action to take, please contact a legal adviser or solicitor.

Legal issues

'those engaged in digital preservation must work within the law as it stands. This requires both a good general knowledge of what the law is, and a degree of pragmatism in its application to preservation work. Such knowledge enables the archivist to avoid the pitfalls of over-cautiousness and undue risk aversion, and to more accurately assess the risks and benefits of taking on the preservation of new iterations of digital work.' (Charlesworth, 2012, p.3)

Intellectual property rights (IPR) and preservation

Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) are a section of UK law that include patents, trademarks, copyright and associated rights - such as the moral rights of the author (see Stakeholders, contract and grant conditions) and performance rights. The preservation of digital materials often requires the use of on a range of strategies, and this creates IPR issues that are arguably more complex and significant for digital materials than for analogue media. If not addressed these can impede or even prevent preservation activities.

What is different about copyright and digital materials?

Among the range of IPRs, copyright has a specific importance when considering digital preservation actions. UK copyright law was developed with analogue material in mind. Traditional analogue materials are relatively stable, and well established legal and organisational frameworks for preservation are in place. The legal framework for undertaking preservation work on digital material is not as well developed and good preservation practices are not always recognised, or allowed for, by existing provisions in current legislation.

Copyright makes a distinction between ownership of the physical manifestation of a work, such as a book or work of art, and the separate right to reproduce it (the right to copy). Digital material by nature does not align to this distinction and can cause confusion when applied in the field. In the case of digital material, core repository practices such as providing access to users and routine preservation activities, often involve the deliberate or inadvertent creation of copies. Without appropriate rights clearance, licences or statutory exceptions these copies may constitute copyright infringements. Digital material therefore poses a different set of considerations for repositories holding this category of content. In addition, unlike physical material, digital material requires consideration of dependencies such as hardware and software which all have their own separate intellectual property considerations.

A second significant difference is the relatively short commercial and technological lifespan of digital material. The duration of IPR in digital materials extends beyond both commercial 'shelf life' and in almost every case the technology on which they depend. This forms a three-fold issue, in terms of procuring licenses to replicate content, licences for software to access content, and rights clearance of "abandoned" digital material, in addition to the added urgency of undertaking these actions.

Copyright exceptions

Although the Copyrights, Design and Patent Act (1988) limits possible preservation actions for digital material, exceptions for archives, libraries and museums have been introduced to address the unique requirements for preserving it. From a preservation perspective the most important provision (Intellectual Property Office, 2014) is the right to produce any number of copies required for the purpose of preserving digital material. Another important exception is the dedicated terminal exception, which enables a digital copy (i.e. one of the copies created under the preservation exception), to be made available on a dedicated terminal accessible to walk in users. These provisions only extend to items held permanently in the collection. The exceptions enables those institutions covered by the exemptions to hold copies of material in various file formats and thereby adhere to what is considered good preservation practice while staying within the law. Note that the copyright exception provisions do not overrule the moral rights of the author which must still be considered when undertaking preservation work.

The exemption to copy for preservation does not however take into account the dependent nature of digital material, and third party software dependencies can still form a barrier to preservation actions. This is particularly an issue observed in preservation strategies which rely heavily on retaining the wider technical environment of the digital objects in question. For example, emulation as a preservation strategy requires use of original operating systems and software external to the repository's permanent collection (see Preservation action). It is important to consider the additional costs and time of maintaining relationships with third party rights holders that follow from dependencies not covered in the exceptions.

Orphan works

For institutions looking to publish digital surrogates of analogue material, the Orphan Works Licensing Scheme run by the UK's Intellectual Property Office, as well as the EU Orphan Works Exception are likely to impact digitisation work and planning. The Licensing Scheme allows for both commercial and (in the case of heritage institutions) non-commercial digitisation of any type of material in which it has not been possible to trace the rights holders of the material following a 'diligent search'. The licence is a pay scheme limited to a seven year period and for use exclusively in the UK. Repositories need to plan and budget for renewal of such licenses. The EU Orphan Works Exception, on the other hand, is restricted to text based and audio visual works only (and artistic works as long as they are embedded in the former), and museums, libraries, archives, educational establishments and public broadcasters. Here, the benefit is that the diligent searches are self certified and the preservation copy of the work, created under the preservation exception, can be placed on line for non commercial uses, for example, thus assisting greatly with digitisation activities.

Access and security