Kuldar Aas is Deputy Director of Digital Archives at the National Archives of Estonia

Let’s get this clear – public records are important. They are the basis for proving the rights and claims of people and organisations, ensuring the transparency of our governments and a crucial piece in preserving a coherent picture of our current societies for future generations. Yet, being a public archives employee myself, I agree there are many aspects which justify the addition of “public records” into the DPC BitList 2019 and in the following I will try to describe some of the most crucial ones from the Estonian public sector point of view.

The first aspect I’d like to mention is – possibly as a surprise to many – the trend of making public information as open and accessible as possible. In this context Estonia has within the last few decades moved from one extreme to another. During the Soviet occupation public records were really “government records” – information was not recorded for the benefit of the people but more for keeping the huge government machinery going. As such the information was not really meant for and open to the public.

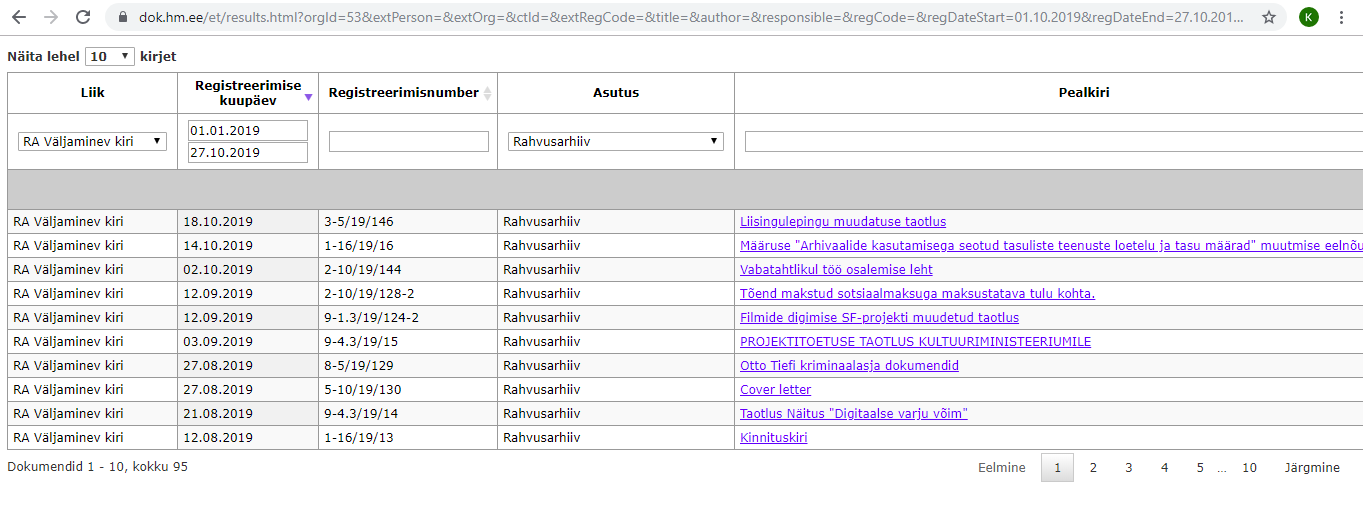

After regaining independence in 1991 access to public records was quickly stated to be one of the main rights of citizens, and the following was added into the constitution: “§ 44. Everyone is entitled to free access to information disseminated for public use.” As Estonia’s independence coincided also with the rise of internet, the Public Information Act added in early 2000’s that all agencies must maintain a document register which "…is a digital database which is maintained by a state or local government authority or a legal person in public law in order to register documents received by the agency and prepared in the agency and to ensure access thereto“. In more simple terms: all Estonian agencies have to maintain a websites which proactively publish descriptions of all their records (both analogue and digital), and also provide full-text search and access to (i.e. possibility to view and download) digital records which are not restricted by Estonian or European laws (read: GDPR).

Figure 1: View of outgoing mails within the public records registry of the National Archives of Estonia

However, these agency obligations have created a situation where the records from the Soviet period can indeed be more informative than the ones created over the last decade or so. Of course I’m not claiming that we should revert back to an oppressive regime, it is just that the public sector employee (i.e. the one creating records) is afraid of the public and especially the media which has found the public document registers to be a good tool for finding “scandals” without much effort. True – there have been some cases where the public registers have allowed media to find out about real misconduct in the public sector, but there are many more cases where the “scandal” can rather be related to some humanly understandable small mistakes by a back-office employee. Of course most public sector employees just want to do their jobs as good as possible without the fear of “public execution”, so the simple solution for them – make records as metadata as generic as possible so that the public and media would not be too interested in them (for example, you can find loads of records with the title “meeting minutes”).

Partly related to the previous but also due to the huge amount of information nowadays is another trend – all relevant information (especially e-mails and social media) is simply not registered as official records. This trend is not only witnessed in Estonia, but across the world. For example, you might want to have a look at a recent presentation by the Norwegian National Archives highlighting similar issues. Just to note that Norway and Estonia have very many similarities in regard to legislation on proactive information publishing.

By now you might wonder if I dream of a full closure of all public records or even the return to a highly oppressive and closed Soviet regime. Of course this is not the case – I do believe that the public sector has to work for the public and part of it is also full transparency and accountability towards the public. I just see that there is still a lot to do in order to make sure that the public employee can use more effective means for documenting and publishing information without being afraid of the “public execution”.

The final aspect I would like to highlight is appraisal. By now I’ve had the chance to listen twice to the excellent keynote by Dr Michelle Caswell on bias in appraisal (iPRES 2019 keynote was recorded and is available at https://vimeo.com/362491244/b934a7afad – make sure to look and listen carefully!). I fully agree with the point, that archivists and their appraisal decisions have a big role in shaping how our current world is perceived and understood by future generations. As such it is indeed necessary that everyone working with appraisal finds, every now and then, time to think whether the principles and methods used are indeed the right ones.

However, the difficulty is that appraisal assumes the availability of information to be appraised. Above I discussed already how proactive publication obligations are making public records less informative, and that a growing amount of information is unmanaged. In the context of appraisal the consequence is that at the same time:

* information that is being appraised is less informative;

* more informative content is “hidden” among huge amounts of irrelevant content in unmanaged locations, making it really hard (and costly) to find and extract them for preservation.

Further, I can’t help but think back at the above-mentioned very informative records of Soviet times. While indeed including a lot of details you always need to be critical about whether the records describe “what actually happened”, or “what the Soviet government WANTED to happen”. In more simple terms – you were not supposed to document the problems of everyday life but rather describe how good and progressive is life in the USSR. While this is not any more an issue in current Estonia, I am afraid that unfortunately there are still regimes where certain aspects around minorities and in general “difficult topics” go undocumented, meaning that there is not much appraisal as such could achieve.

So indeed – I do agree that public records deserve a place on the DPC BitList. However, they are not there just for the reasons of technical file format, media and information system obsolescence, but rather because the traditional methods of managing information as records (and as such the usual principles of classification, description, publishing, appraisal and preservation) are outdated and not necessarily fit for modern information technology and public demands for transparency. Luckily work has already started in this field, for example the European national archives have recently defined the work on novel “archiving by design” principles to be a priority for EU-wide collaboration (you can find the minutes of the relevant European Archives Group meeting here), and in Australia the Monash University has published a book addressing partly the same issues already in 2017. Of course I intend to contribute to this work the best I can, and I also invite everyone who has indeed managed to keep reading this post until the end to join in, share your ideas, best practices and technological innovations which help public archives to appraise, collect and preserve an accurate representation of the world we’re currently living in!