Nick Bywell is the Digital Library Developer in the library of the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). He recently attended the PV2023 Conference at the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (CERN) with support from the DPC Career Development Fund, which is funded by DPC Supporters.

While at the PV 2023: Adding value (to) and preserving Scientific & Technical data conference, I heard the question posed “Does antimatter fall up or down?” It’s not the sort of question one usually hears at a digital preservation conference, and it took me back to 2012 when I watched the announcement of the confirmation of the existence of the Higgs Boson on television. I didn’t imagine that, as a non-scientist, I might one day be sitting in the same auditorium.

The main auditorium

I was asked by the DPC to choose a particular theme on which to write a blog post relating to the conference. I was spoiled for choice, as there had been a presentation on NASA’s Mars Rover Mission, various presentations on the Earth Observation Satellites of the European Space Agency (ESA), two on software emulation, and many others. However, I chose the workflow associated with the data of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) because processing at such a scale poses interesting challenges, and CERN’s aim of determining the nature of the universe is an ambitious one. Also, there are a few common factors with the data workflow at the library of the LSE, which indicates that the standards and tools developed by the archival community are scalable.

We heard during the opening plenary session that when the two streams of particles collide, after being accelerated around the 27km accelerator, they do so at a rate of approximately 2 billion collisions per second. This quantity poses the first challenge for those responsible for data-processing and they have met it by having an initial bank of detectors that can identify, within nanoseconds, whether the collision is “interesting” or not. If it is not “interesting”, the data relating to the collision is not captured by the subsequent banks of detectors.

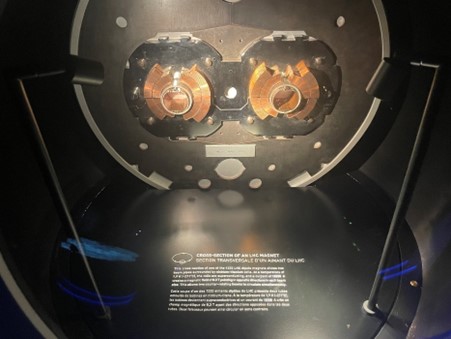

A cross-section showing the two beam pipes of the LHC.

The software engineer leading the development of a digital preservation platform for CERN is Antonio Vivace, and during his presentation titled “The Challenge of Digital Preservation at CERN” we learned that despite this data-filtering measure, the quantity of data that has to be processed and stored is such that spare capacity at other scientific institutes around the world is utilised, so a significant proportion is distributed across various nodes on the Worldwide LHC Computing Grid (WLGC).

For the digital preservation part of the process, the Open Archival Information System (OAIS) Reference Model is used. The data and metadata for this purpose are harvested from various upstream repositories.

CERN was one of the four organisations in the “Buyers Group” for the ARCHIVER project that has been investigating possible new approaches to long-term digital preservation at CERN as part of a tender process for petabyte scale digital preservation. Matthew Addis is the Chief Technology Officer of Arkivum, the company responsible for providing one of the pilot solutions.

In his presentation titled “Scalable, efficient and environmentally sustainable Long Term Digital Preservation of scientific datasets in the ARCHIVER project”, he talked about how the carbon footprint of cloud based solutions could be quantified. The Google Cloud Platform (GCP), which Arkivum utilises in the ARCHIVER project, provides data on the gross carbon emissions corresponding to energy use by their servers and storage. The gross figure for the carbon footprint involved in processing one petabyte of data and storing it for one year using the Arkivum solution in GCP is approximately 7800 KgCO2 eq. The net figure will be significantly lower because Google uses renewable energy and offsets residual carbon emissions.

Finding the separate figure for the “Embodied footprint”, which represents the manufacture and disposal of the servers that process and store the data, is more difficult because it involves taking the net figures (after offsetting) provided by the manufacturer of the servers and making various estimates before coming up with a figure of approximately 4000 KgCO2 (net) for one petabyte of storage for one year. Whilst ARCHIVER piloted cloud-hosted solutions, tape storage is still very much part of CERN’s current production approach because of its low cost, and its relatively low carbon footprint, compared with server storage.

These figures for environmental sustainability will be of interest to my employer because the digital collections in the library of the London School of Economics (LSE) are uploaded to Arkivum using the OAIS model. It is a proprietary hosting platform that utilises the open source digital preservation package Archivematica and the open source archival dissemination package Atom. An instance of the latter forms part of the LSE’s digital library offering.

The view over the servers at the data centre

The home page of the WLGC gives a figure of ~200 Petabytes of data produced by the LHC every year. It is possible to access several petabytes of this data via the CERN Open Data Portal.

With regard to the question “Does antimatter fall up or down?”, the answer is that it seems very likely that antimatter does fall in the same way as matter but there’s still work to be done.

This question about antimatter was posed in a Q&A session following a visit to the Sychrocyclotron, which was the first of the accelerators installed at CERN, and began operation in 1958 and ceased in 1990. There is a plan for a successor accelerator to current the 27km LHC, which will have a circumference of 91km.

The Synchrocyclotron

A view across the Geneva waterfront in the late evening, taken while relaxing after the conference.

Acknowledgements

The Career Development Fund is sponsored by the DPC’s Supporters who recognize the benefit and seek to support a connected and trained digital preservation workforce. We gratefully acknowledge their financial support to this programme and ask applicants to acknowledge that support in any communications that result. At the time of writing, the Career Development Fund is supported by Arkivum, Artefactual Systems Inc., AVP, Ex Libris, Iron Mountain, Libnova, Max Communications, Preservica and Twist Bioscience. A full list of supporters is online here.