A Note from the Editor, Sara Day Thomson

As the coordinator of the DPC’s Web Archiving & Preservation Working Group, it has been my absolute pleasure to work with some of the most enthusiastic, creative, and persevering professionals in the field. The community of archivists, curators, librarians, researchers, and enthusiasts who do the work of capturing and preserving web resources has always displayed a collaborative spirit and a willingness to try new approaches and learn from each other.

The coronavirus pandemic has truly and profoundly put that spirit to the test, and the web archiving community has not disappointed.

‘The speed, scale, and level of interest in participating in this collective effort have been remarkable and have no comparison to previous collaborative endeavours,’ Jefferson Bailey from Internet Archive attests. ‘It is a great testament to the community's ability to work together.’

Over the last couple of weeks I’ve been in touch with a handful of the professionals at the front lines of this effort to archive the global experience of coronavirus. In a series of blog posts, I’ll share their insights into the urgent undertaking to capture the world’s response to coronavirus (Covid-19) online.

Quick note to say, if you’re really just interested in practical guidance on how to archive web content, check out instalment 2 of this series. For practical guidance on archiving social media, scroll to the end of this post.

In the last instalment, we heard from the Web Archiving Team at The National Archives UK about their 3-pronged approach to capturing the UK Government’s response to the coronavirus outbreak. To those of us ‘in the industry’ it may seem self-evident why teams like the one at TNA and others around the globe are racing to capture content about the pandemic. Through collection policies, organisational missions, and user needs analyses, archivists, curators, librarians, and other information professionals are well acquainted with the motivations and even mandates to collect and document major events.

These collections - from the global collaborative effort coordinated by IIPC, to the projects added to the Society of American Archivists’ on-going list of Covid-19 web archiving initiatives - have vital importance beyond the world of collecting institutions. These records have the potential to provide unprecedented insights into a global event. They are valuable for researchers in almost every discipline from epidemiology to public policy; to local and international health organisations; to journalists and film-makers and artists; to policy-makers and government agencies; and perhaps most of all, to the humans who are living through this historical moment and for future generations.

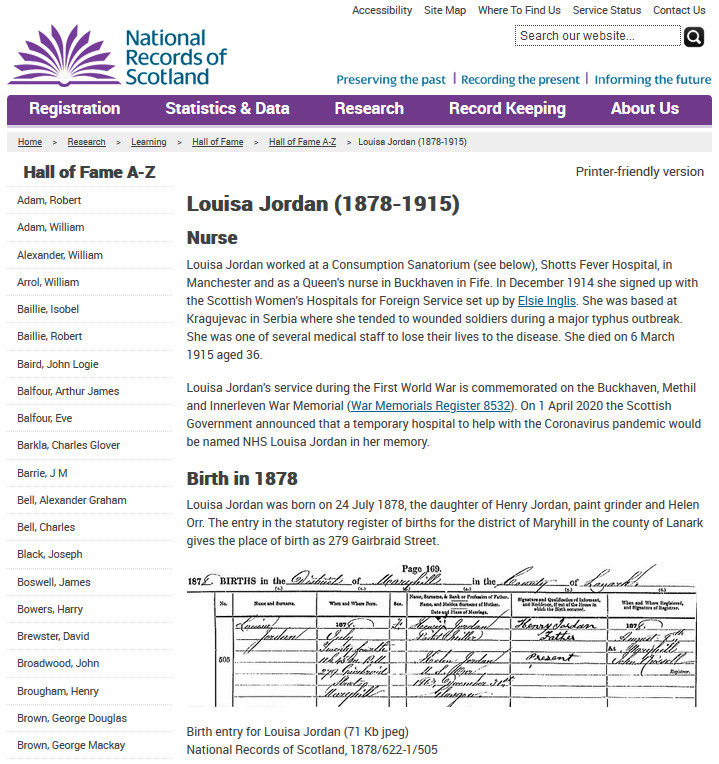

Among the tsunami of news about the pandemic - the updated death tolls, the hemorrhaging economies, the beleaguered health services - we’ve seen (here in the UK) the odd archival object pop up in our newsfeeds. For example, the digitized photographs of makeshift hospital wards during the Spanish flu pandemic following WWI. In Glasgow, where your faithful narrator composes this post, a new coronavirus hospital has been named after nursing sister Louisa Jordan from Maryhill who died treating soldiers during the typhus outbreak during WWI.

These images and their associated archival records have a lesson to teach us - that they should teach us - about how to respond as a society. How to reduce the loss of life, minimize economic decline, and curtail human devastation. While many governments may have been slow to make use of these lessons, some government and health officials have benefited from access to these documents.

The information published on the web about the coronavirus outbreak will become for future generations what the fuzzy digitized photos of makeshift hospital beds are for the present. Although preserved in WARC files - the standard format for archived web content - rather than temperature controlled archive stores, these resources will provide a record of this historical moment. As Jefferson Bailey from the Internet Archive asserts: 'This unprecedented moment reinforces the fact that web resources are critical historical records, even as they remain highly ephemeral. Archiving this event is not possible without archiving the web.' Information about the coronavirus outbreak - official publications and public responses alike - exist largely online. Through capturing this plethora of information, collecting institutions are able to document the particular coronavirus realities of their communities.

In Ireland for example, Web Archivist Maria Ryan and team at the National Library of Ireland are ‘working to capture the online response in Ireland to the Covid-19 outbreak.’ Maria details the aspects that shape the Irish response to the pandemic online: ‘Similar to other events such as Brexit, elections and other national incidents, we are focusing on capturing the record. We are archiving the websites of the Irish government and the Health Service Executive as well as the Irish media. We are also identifying sectors affected by the outbreak and organisations such as charities who are supporting vulnerable groups. We are also archiving the Irish public's response to the outbreak and recording how Irish communities are reacting.’

In Luxembourg, Ben Els from the Bibliotheque Nationale explains: ‘Capturing information from the Luxembourg perspective is different from other events because the situation in other countries highly influences what happens here. For example, since a lot (if not most) health care workers commute from neighboring countries, the closing of borders is a crucial topic in Luxembourg politics and the news.’ Though the closing of borders has widespread implications for countries all over the world, as Ben points out, in Luxembourg, those implications have a direct impact on their ability of health care workers to deliver life-saving treatment. Archiving web resources about coronavirus in Luxembourg will help to document the adverse consequences of this major political decision.

In the US, the Library of Congress Web Archiving Team has identified and started capturing resources that reflect the American response to the outbreak. ‘At a time when we are spending so much of our lives online, the artifacts of this time will also be online. Given the wide-ranging impact that the pandemic is having, our regular crawls of sites across collections will capture developments as events unfold – collections on news, Business in America, and food and foodways come to mind, as well as cultural documents found in sites like Know Your Meme. The nature of web archiving means that our day-to-day work is contributing to the historical record, and this is especially important now as we preserve a point in time that will be of great interest to future researchers.’

These web archiving approaches all provide a window into how the outbreak has affected communities (households, cities, states, countries) in different parts of the world. Collecting websites from government and health organisations tracks the decision-making of policy-makers and tracks shifts in guidance as new information emerges from medical and other scientific research.

Besides official websites, however, there is another web resource that reveals important information about the coronavirus outbreak, especially about what everyone else has to say: social media. While any good social scientist will tell you there are limitations to the representativeness of social media data, platforms like Twitter and Facebook provide a unique glimpse into what people are saying about the outbreak - how it affects them and what they’re worried about. Social media data, captured from an API along with rich metadata, provides a valuable tool for tracking the spread of information across networks (accurate or otherwise). As Ben Els reflects, ‘I think that this is also a good time to point to the importance of web archiving in terms of combatting online misinformation and capturing history for future generations.’

At George Washington University (GWU), the creators of Social Feed Manager (SFM), an open source tool for institutions to capture and curate social media collections, are busy harvesting Twitter data related to the coronavirus outbreak. Just as they have used this powerful tool to collect responses on social media to past events, they’re targeting relevant hashtags to generate collections that will be useful for a variety of types of research.

Dan Kerchner and Laura Wrubel from the team at GWU describe their approach: ‘As part of our proactive collecting strategy, where we start collecting around a major event we know researchers will be interested in later, we set the collection up using broad hashtags. Using broad hashtags is more likely to be useful to a wider range of research interests, and we are in fact providing subsets to GW researchers around more specific terms and topics.’

Because researchers are interested in the data now, the team is regularly releasing datasets.

‘We are regularly loading updated datasets into Tweetsets and Harvard's Dataverse platform, making the data available to researchers at GWU and beyond (tweet identifiers only for non-GWU researchers). Data through March 31 can be accessed at:

- Harvard’s Dataverse (Tweet IDs only)

- Tweetsets (non-GWU users can derive subsets of Tweet IDs; users on the GW network can download full tweets)

Due to re-use restrictions imposed by Twitter’s Developer Agreement and Policy, the team at GWU can only release Tweet IDs (not full tweets) outside the University, but for academic use, these Tweet IDs can be ‘rehydrated’ with full tweets using a tool like Document the Now’s Hydrator. You can learn more about rehydrating tweets in this blog post by The Distant Librarian (or Paul R. Pival, Librarian at the University of Calgary).

The ‘wide range of research interests’ using the SFM collection include medical disorders, public health messaging, and external links embedded in tweets about coronavirus. Dan and Laura describe the projects making use of the data so far:

‘There are already several research projects at GW working with the Coronavirus Twitter dataset:

- Researchers analyzing subsets of the collection containing tweets in a specific language (e.g. Spanish, French, Persian)

- Medical students looking at subsets of the data discussing gastrointestinal disorders within the context of COVID-19

- Public Health researchers studying official messaging within specific communities (e.g. Spanish-speaking, Portuguese-speaking) and locations (Puerto Rico)

- Researchers exploring which external websites users are linking to from within tweets discussing COVID-19’

The SFM team at GWU is only one initiative collecting social media data related to the outbreak. The University of Southern California is also collecting Twitter data around the pandemic and making Tweet IDs publically available. In fact, institutions all over the globe are collecting social media as part of their collection strategies for documenting the pandemic. The National Museum of Australia has created a Facebook Group dedicated to collecting Australian ‘experiences, stories, reflections and images from the pandemic’. Stanford University is collecting social media in addition to crowd-sourcing materials through an open call for ‘diaries, videos, images, email, creative projects’ and any other formats community members are using to document their experiences.

These initiatives, planned and launched within a rapid timescale, will result in an unprecedented volume of invaluable (if often devastating) collections. All around the world family members are falling ill and many of them dying in hospital, quarantined away from their loved ones. Workers already struggling under precarious contracts are losing their jobs and relying on government aid, where there is any. Entire economies and sectors are crumbling under lockdown restrictions in place to save lives. For those of us living this pandemic in real time, the situation is raw, uncertain, rife with fear, anger, and confusion. Web and social media archives have the potential to one day provide the basis for clarity and understanding, for holding governments to account for their preparedness and decision-making.

However, these archives are only as valuable as they are accessible and only as effective as they are used. Jefferson Bailey from the Internet Archive asserts: ‘This event reminds us that we are all in this together and reiterates the importance of open access to information, be it for accelerating scientific research or for those stuck at home without access to schools or libraries. Internet Archive fully intends to make data from our COVID-19 web archiving available to others - researchers as well as other memory institutions.’

Information professionals will look after the WARCs - archived web and social media files - as we have looked after the grainy photos of makeshift hospital wards and all the records that make up our historical experience. However, it will be up to future users to tell us what these WARCs would say if these WARCs could talk.

A huge heartfelt thank you to all the busy web archivists who took time out of their superhero days to share their experiences with me. Especially thank you to Nicola Bingham Lead Curator, Web Archiving, British Library, Ben Els, Digital Curator, Bibliotheque national de Luxembourg, Silvia Seville in Web Preservation at the EU Publications Office, Jefferson Bailey, Director, Web Archiving & Data Services, Internet Archive, Maria Ryan, Web Archivist, National Library of Ireland, Claire Newing and Tom Storrar, UK Government Web Archive, UK National Archives, and Abbie Grotke and Team, Web Archiving, Library of Congress.

Appendix: Practical Guidance for Archiving Social Media

If you or your institution is looking for advice and guidance on archiving social media, I recommend having a look at the resources below.

Papers and Guides

- ‘Preserving Social Media’, DPC Technology Watch Report: http://dx.doi.org/10.7207/twr16-01

- (The digest version) ‘Preserving Social Media’, DPC/NAI Topical Note: https://www.dpconline.org/docs/knowledge-base/1869-dp-note-8-preserving-social-media

- (More about API-based harvesting) ‘API-based social media collecting as a form of web archiving’, Justin Littman, Daniel Chudnov, Daniel Kerchner, Christie Peterson, Yecheng Tan, Rachel Trent, Rajat Vij & Laura Wrubel, International Journal on Digital Libraries: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00799-016-0201-7

- (Do It Yourself / Personal Digital Archiving) Save Your Social Media: a quick 'how-to' for downloading your valuable photos and content shared online: https://www.dpconline.org/blog/save-your-social-media

Tools

- Social Feed Manager: open source tool for harvesting social media data from APIs for Twitter, Flickr, and a couple of platforms, designed for institutional use. An overview here.

- TAGS: an open source tool for harvesting Twitter data using Google Sheets (requires a Google account and a Twitter account)

- Webrecorder: an open source, web-based tool for capturing social media as webpages. An overview here.

- Tools for capturing Twitter data from Wasim Ahmed’s LSE Blog post ‘Using Twitter as a data source: an overview of social media research tools’ (2019)