Jack Wain is Coordinator, Digitisation and Preservation at Deakin University Library

University collections come in many shapes, formats and sizes, and typically involve a large variety of interconnected systems, discovery platforms and repositories, often accrued and integrated over many years – even decades. These systems will also often have their own data analysis tools or reporting functions, or have integrations set-up for this task, and as a result it can sometimes be difficult to grasp the sheer volume of digital files in the entirety of a collection because your data points are gathered separately. This is even further complicated in situations where ownership or responsibility for the collections varies, or in cases where documentation has been developed independently by numerous teams.

Having a single datapoint makes it easier to understand the specifics of what you need in terms of digital preservation enhancement and – when combined with appropriate maturity modelling – helps plot the course towards implementing targeted digital preservation improvements.

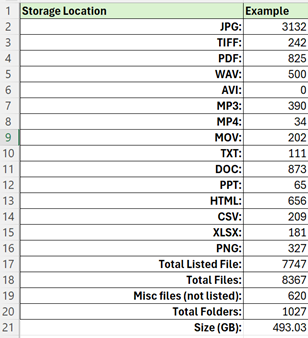

Employing toolkits like digital asset registers allows us to capture a high-level snapshot of our digital holdings at a collection or sub-collection level, which can be great in facilitating discussions when advocating for change. However, I have found at times that I wanted a more granular approach to digital collections, like knowing exact file counts or what format types are present across a given repository or storage space, or even getting a sense of how many files are present that SHOULDN’T be there. To answer these questions, I took the ideas that help underpin tools like asset registers, and began building a tool to help audit our digital collections.

Built in Excel, the audit tool helps me parse manifests extracted from a variety of databases, as well as summarise full directory lists that can be generated using simple programs, such as the base Windows cmd line or PowerShell. The most common file formats we expect to find in our digital storage spaces were listed out, but any file extension can be accounted for. A total size was also extracted and provided in GB.

Fig.1 – example of Audit Sheet format list breakdown using test data

While this type of tool is not new, and more complex tools certainly exist and are in use at institutions further along in their digital preservation journeys, I found this helpful as a low-tech, low-barrier approach to assessing our large and varied digital collections and getting a snapshot of the material in a more controlled and methodical way.

As we are doing this work in processing, managing and enhancing projects and collections internally, the library is at the same time interacting with a wide variety of university communities to support their research and teaching needs. These interactions have highlighted and made clear that there is need for the complexities of digital preservation – and the understanding that comes from working practically in the space – to be distilled and communicated to individual users operating outside of a clearly defined digital infrastructure, but who nonetheless intend to generate digital material and want to ensure that it is managed appropriately, from creation to preservation.

While the fundamentals of digital preservation can sometimes seem straightforward, perhaps deceptively so, it can be a dense space to engage in. This is especially true if it is not typically an aspect of your day-to-day. It can be a bit like entering into a roundabout in a country where the road signs are in a language you don’t speak – you can recognise that you’re in a roundabout, and can understand the basics through context-clues, but knowing exactly where and when you need to turn off can be a bit trickier.

A researcher or an academic may come to us for advice or assistance in understanding their responsibilities in creating digital material, or the practicalities of managing said material, and as we’ve positioned ourselves as an intersection for knowledge – whether that be on an individual, institutional or industry-wide level – it’s up to us to find the right language, methods and format to succinctly convey the appropriate information.

With resources like the Digital Preservation Toolkit for Community Archives about to be launched, which aims to demystify digital preservation for smaller digital material holders, it’s got me thinking about what a similar resource aimed at individual researchers or academics might look like, specifically in the context of their interactions with the university library. A key component of advocacy is education, and a critical aspect of effective education is contextualisation.

Looking ahead, I’ll be trying to take what my own work has taught me about the value of stepping back and compartmentalising big pieces of work, as well as the interactions that we have in the library, and thinking about how I can best try to combine the two into something more tangible. What I have learnt in using Excel to audit the material I work with is that sometimes simplicity is key. By using something familiar with a reasonably low level of complexity - but a program nonetheless appropriate for the task at hand - I was better able to visualise important aspects of digital preservation that needed to be addressed, and from there begin having those larger conversations with people, using the spreadsheet as a recognisable foundation.

So when I think about how best to communicate digital preservation to individuals who may only now be thinking about it all for the purposes of a single project, I think about how the first step might just be getting to a common, familiar starting point. There is no single answer to the question of “how do we communicate digital preservation?” because the reality of it is: it depends. It depends on who you’re talking to, what they already know, what they can feasibly do, and an incomprehensible number of other factors that are unique to the specific context in which someone is engaging with digital preservation. And in lieu of there being a simple answer, the work that I and many people in the digital preservation space do becomes about explanation and simplification and using a multi-faceted approach to find the right words, framing and context.