Lee Hibberd is the Digital Preservation Manager at the National Library of Scotland.

For more than a decade the National Library of Scotland has been on a journey to achieve one of the digital preservation fundamentals – safe storage. In October 2020, and for the very first time, we achieved our goal of keeping 3 copies of our preservation data. To mark the coincidence of this result with World Digital Preservation Day I’d like to share the ups and downs of the climb with you - from the foothills to the clouds.

Between 2000 and 2010 the National Library of Scotland had an established Digital Preservation Programme, was purchasing digital content and collecting Scottish websites and personal archives with digital bits attached. Growth was manageable and routine – one copy lived on networked disk storage, and another on back-up LTO tape. We were early and full members of the Digital Preservation Coalition and had attended our fair share of training but data losses remained as words on a PowerPoint slide. It wasn’t long before the theory became personal.

Data losses

In 2008 a routine firmware upgrade for a piece of network equipment corrupted around 2500 digitised master image files. At the time that was 2% of all our masters. We had written about, but not deployed, routine fixity checking and so had to manually inspect 30 thousand images to find those affected. And the tape back-ups? The indexes on the tapes had failed and we could not restore the affected files easily. To identify and re-digitise the content cost the Library £13,000. If we scale the problem to today’s digitised collections the cost would be close to £800,000. The standard back-up approach was failing.

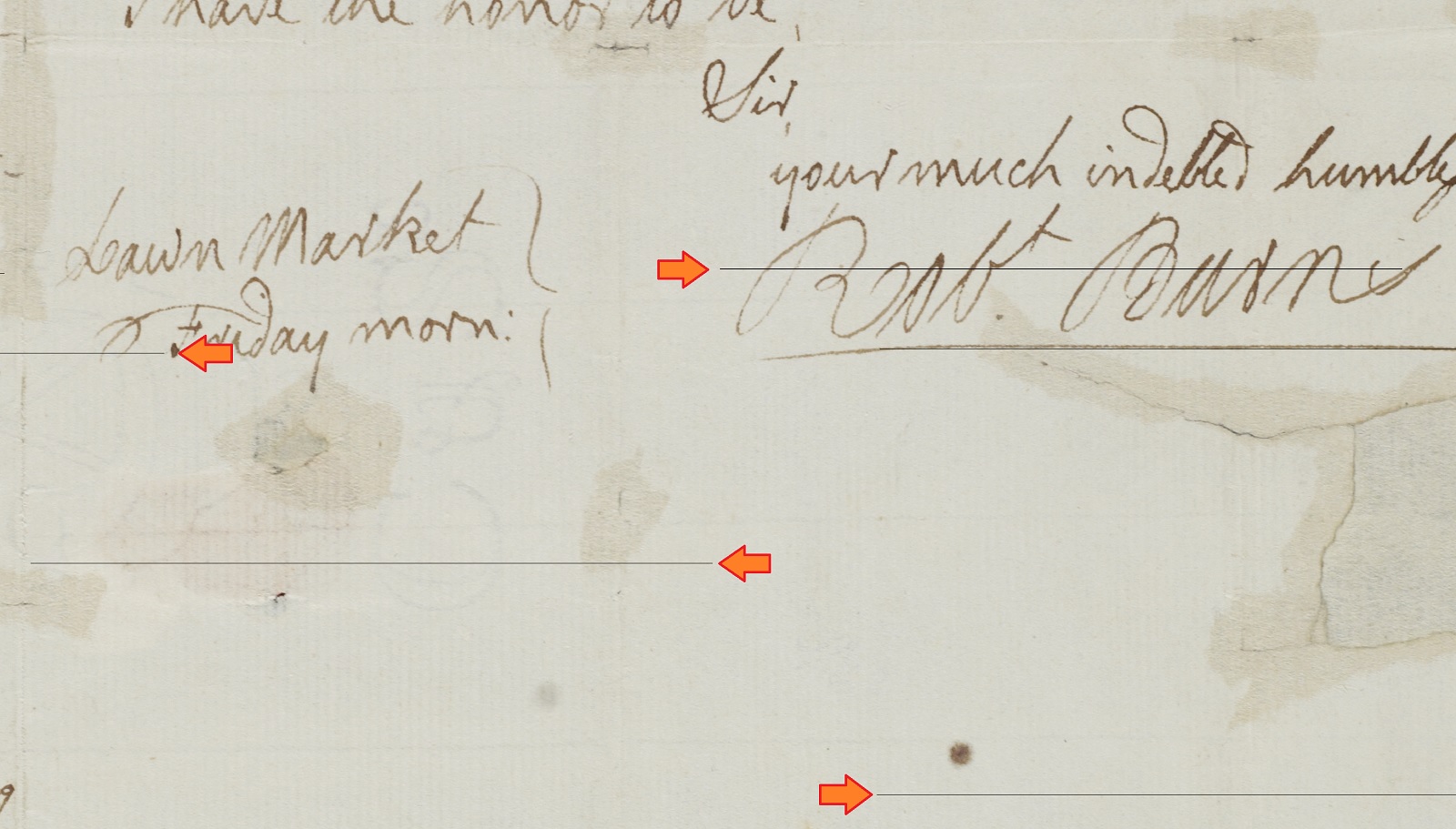

Figure 1: Corruption lines running through a digitised manuscript from Scotland's bard, Robert Burns.

From 2009 onwards preservation data was fixity checked annually with a PREMIS audit trail of events recorded in our preservation database. Checksum mismatches highlighted issues with our ingest procedures, which were improved, and very occasionally identified errors with copying files between locations. Fundamentally we could now save tens of thousands of pounds and many months by using a computer and not a pair of human eyes to identify files which had changed since our last check. Furthermore it would scale with the growth in digital content.

Leadership and longevity

After 2010 an injection of cash allowed us to buy new storage and for a short while, and for some of our preservation data, we could experiment with keeping 3 copies. As content grew and we pooled our infrastructure with other public organisations to meet government targets the experiment ended. We were back to 2 copies and had revealed a new challenge: The Library needed to commit to long-term sustainable storage for its preservation data in a way that would be supported by, and outlive changes to, its leadership team (the National Librarian, the Head of Finance, departmental Directors) and government initiatives.

Busting tape heads

Meanwhile more practical issues were hampering our use of tape back-ups for our second copy. We were destroying tape heads by writing millions of small files, and when trying to restore a couple of TIFFs we learned that the standard “snapshot and incremental” back-up approach we’d used for 15 years was not our friend. We had not kept the log files which told us which files are on what tape and could not recreate the log files without loading every tape in the right order. We had hundreds. To make things harder, once we had identified the tape required we would need to load more than 10 related tapes to restore the couple of files we were looking for. This could take a few weeks to slot into our IT team’s schedule. Do not underestimate how big a barrier human inconvenience is to doing the right thing.

The second climb

2016 marked the start of a fresh attempt to scale the storage peaks. After seeing we were behind our peers the Library’s Leadership Team approved, subject to an understanding of the costs, the creation of 3 copies of preservation data. Three geographically separate copies would be kept, two copies would be annually fixity checked with the third sampled. One copy would be stored offline and 1 or 2 copies would be stored in a way that prevents overwrites.

The earlier flaws in tape back-ups were resolved. We stopped incremental back-ups which reduced strain on our tape system. Preservation data was now zipped up into tape-sized-chunks and the location of the files and tape recorded in our preservation database. We only needed access to a single tape to restore 1 file and we knew where it was. But even this optimised process would not be able to scale with our projected growth without a substantial investment in our tape system. This moment of reflection led to a radical shift away from tape and the sacrifice of one of our ideals: to store a copy offline.

I love tape for several reasons – a published path to increased capacity and transfer rates per pound, its low media cost, and the fact that you can remove the tapes from the network and protect the data from network attacks like ransomware. But there are disadvantages too. Without a large and sophisticated tape system with robotic access to all of the tapes you cannot quickly work with the data, and even then it is much slower than disk. Was it possible to reduce the risks of network attacks in other ways? We thought so.

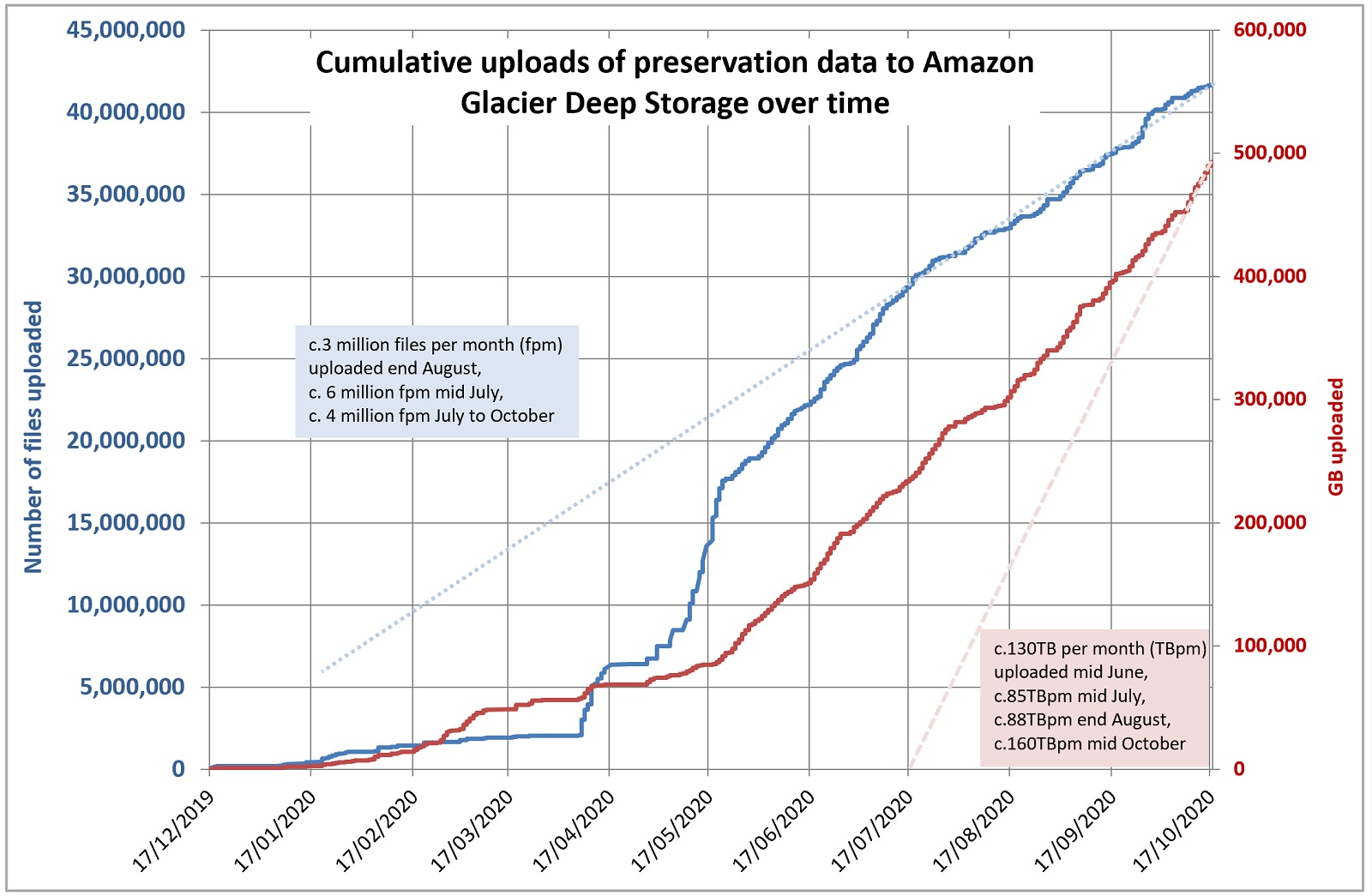

Between 2017 and March 2020 we had procured, installed and migrated 350TB of preservation data to our new storage from HP and Scality that created a local cloud in Edinburgh and Glasgow using Amazon’s S3 protocols. This provides high-speed access and replication, supports fixity checking in both locations and the sites can run independently of each other. At the same time we were uploading the elusive third copy to Amazon Glacier Deep Archive through a 1 Gigabit internet connection shared by two virtual machines running 24:7. In October 2020 more than 40 million files and 490TB of preservation data is “in the cloud”.

Figure 2: Almost 500TB of data has been uploaded to Amazon in 10 months via the Library's 1 Gigabit Internet connection. This link is shared with the Library's staff and visitors. Over the year we have refined our processes and if we started again we could do the same job in 4 months.

The keen eyed among you will spot that this third copy is not offline, but it is encrypted before it leaves the Library and is set up to prevent overwrites, deletions and requires multi-person authentication to access the account. Many of these principles apply to the first and second copies in our local clouds and it is safe to say that we are doing the best to safeguard data now than at any time in our history. But there is still much to do and questions to answer. One common question is how far can the remote cloud go? Should we put in 2 copies, 3 copies? If Amazon creates 3 copies for us as back-up then isn’t one copy with them good enough? Will paying more for more benefits in the cloud affect our commitment to sustainably care for our existing content? How are budgets managed over time to allow for switches from one storage combination to the next should, for example, the costs increase or a particular service be withdrawn?

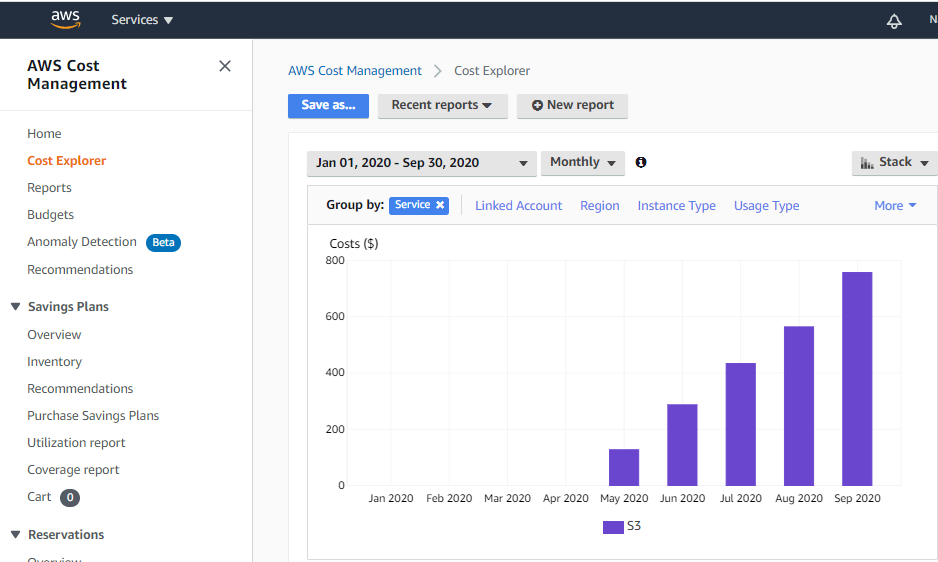

Figure 3: Monthly storage costs are easily tracked in Amazon and Glacier Deep Archive costs are low, but will build up over time. For the month of September it cost almost 800 USD for the Library to store around 350TB. When we consider all of the costs related to storage we estimate we pay 70GBP (Great Britain Pounds) per TB per year to store and annually fixity check one local copy. This compares to 50GBP per TB per year to store a copy with Amazon, but only fixity check 1TB per year.

The view along the ridge

The National Library of Scotland’s position is always updated by the technology on offer, and its costs, and our ambitions. As a member of government’s extended family we are influenced by larger digital shifts too. But let me have my own personal view from one mountain summit to the next. Multiple cloud vendors offering competitive rates for preservation storage is essential. At the moment the gaps in cost between Amazon and Google and Microsoft are too great. The costs and time of downloading a copy as you move data from one solution to another may mean that is cheaper and better to always keep one copy locally. There is also an issue of sovereignty and value. Why should digital culture be valued less than the material treasures the National Library of Scotland provides to the public? Would it be acceptable for our books, maps and manuscripts to be stored in another country, even if it was stored at less cost and perfectly, on a granite mountain, high above the floods of the future?