Mari Allison worked as Digital Preservation Intern at the Getty and is now Digital Collections Specialist at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History

The DPC’s Museum and Galleries working group has been in place for almost a year and a half, and I’ve had the opportunity to join in their meetings during my year at the Getty. I always learn a lot when others discuss their projects, and I’d like to elaborate on a project we’ve mentioned briefly in those meetings, Time Based Media (TBM) artworks at the Getty Museum.

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Purchased with funds provided by the Photographs Council.

Stephanie Solinas, Vie d’Alphonse Bertillon #05, negative 2012; print 2023, Gelatin silver print and digital sound files, 18.1 × 26.9 cm (7 1/8 × 10 9/16 in.)

© Stéphanie Solinas

Inside the Getty Museum, the collections range from early antiquities to 20th century outdoor sculptures. The Department of Photographs collects materials from the creation of the medium to the present, which now includes TBM. They possess a few TBM artworks and have recently decided to focus more on their preservation.

Although the Museum’s conservators manage the physical carriers, our digital preservation team did not have policies or workflows in place for the digital content when the Museum Registrar first reached out to us.

We created two policies as part of a TBM preservation plan, and these policies are actively evolving as we work through the project. The first is a general overview of preservation decisions, including file naming conventions, fixity checks, and access restrictions. I will primarily discuss the second policy, which focuses on descriptive metadata. Although the digital assets will be deposited in Rosetta, our digital preservation system, we decided that The Museum System (TMS) should be maintained as the system of record for the artwork. TMS is a more familiar system to the Registrar’s Office, and it contains much more information, including details about related objects, exhibitions, and loans. Therefore, the scope section of the metadata policy states that “the overarching goal of descriptive metadata in Rosetta is to have only enough information to understand what is being preserved and what can be done with that content and to be able to reference the source system (i.e. TMS) for more detailed information as needed.” Additionally, it is the Registrar’s responsibility to add the Rosetta PID to the object record in TMS.

The bulk of the metadata policy maps fields in TMS to Dublin Core elements and describes how they should be used. TMS is not a system I would typically work with, but our colleagues in the Museum provided training. Many of the fields like title and creation date are straightforward, but I want to highlight a few that provoked conversation.

dc:format

This field specifies the number of files, digital/analog, type, and running time. We also realized that it would be helpful to state if a video is silent. Over time, I expect the list of things that dc:format covers to expand. Depending on the complexity and composition of artworks that we acquire, additional important characteristics to document will likely be identified.

dc:description

Description is used twice for distinctive purposes. The first entry is meant to describe the relationship between the preserved files and the complete artwork. For example, Stephanie Solinas’ Sans titre (M. Bertillon) consists of 23 print photographs and 24 sound recordings. We only ingested the digital audio files, while the Museum conservators are responsible for the photos. However, we still want the full context to be known through dc:description.

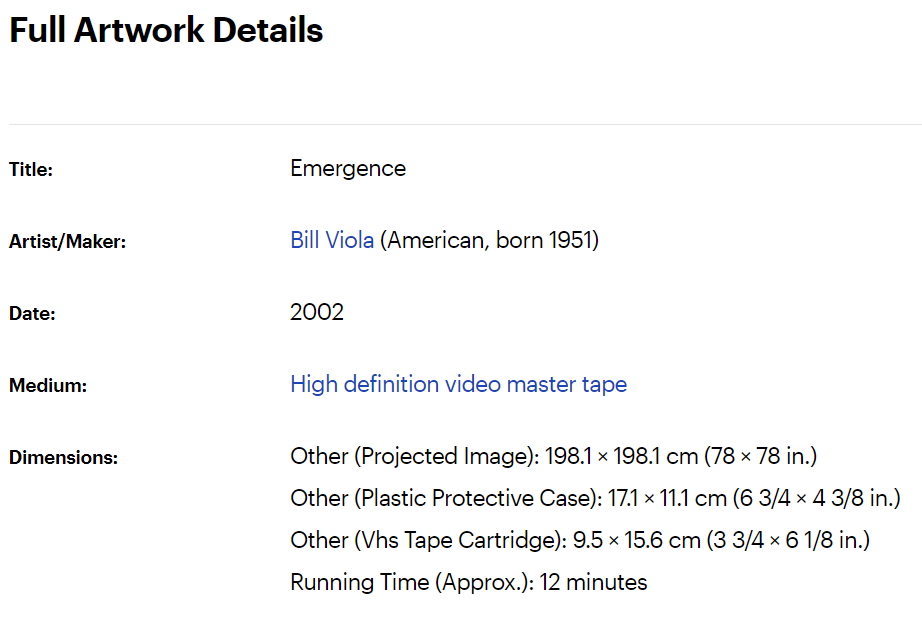

The other use is to describe the source of the files. This could mean the analog source or any other information regarding where the registrar obtained the files. Here is an example from the entry for Bill Viola’s Emergence, the first TBM piece we deposited: “Digital file in VOB format previously stored on Network. The Museum Registrar’s Office is searching for a better version for ingestion.”

Screenshot of one section of the Getty Museum’s collections page for Bill Viola's Emergence https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/108VM9

This example highlights how difficult it can be to trace the source of these files, and lacking access to the originals can be problematic for preservation. Some of the digitized videos are low resolution or have artifacting. I am not an AV expert, and without the original to compare, I don't know if the artifacts are from digitization, media carrier degradation, or simply an artistic choice by the creator.

In another case, we have access to both the original CD given to the Registrar’s Office by the artist and a set of digital files that we assume were pulled from the disc by a predecessor. The digital files contained many artifacts, so I took the CD to one of our digital forensic workstations to view the artwork. The CD actually looked the same as the digital files, but it was still valuable to be able to confirm that. Ideally, we would always be able to trace the original materials provided by the artist.

Working with this type of material was a new experience for the digital preservation team, and our approach is still evolving. We anticipate making continuous changes to the policies we’ve crafted as we continue to work through the collection, and each of the 3 ingests we’ve completed so far has been a rewarding learning experience. We hope to have more to share with our DPC colleagues soon!