Amie Martin (Gamilaroi) and Gulwanyang Moran (Birrbay & Dhanggati) of the First Nations Community Access to Archives project at the Museums of History New South Wales

Under Article 13.1 United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Aboriginal peoples have a right to be self-determining in relation to their Languages, Knowledges and Cultures.

The importance of accessing archival materials is fundamental to not only language revitalisation but to connect First Nations people back to ancestors, reclaim cultural practices and shed our own light and shadows over the information found in colonial records. Further, there is a truth-telling connection to historic injustice, bridging a gap to connections thought to be lost.

Archives hold a power, a power over accessibility, over the impact of records on First Nations peoples and narratives, allowing them to explore past histories.

While these archives cast a dominating white shadow, they also trace another history. This invisible history can be seen through the almost breathtakingly complete absence of our voices within these spaces and texts. There are glimmers and whispers and we can read through their colonising archival lies. This is a history that we can collectively give life to; our Nunga histories of creative resistance, our histories of collective love transforming abjection, and our histories that are deeply engaged in survival. We cast our own shadows. We shed our own light; it can be found shining in the midst of oppressive times. - Baker et al. 2020, p 856.

The NSW State Archives Collection holds valuable First Nations language and cultural information documented in Australia since 1788. The First Nations Community Access to Archives project is a partnership between Museums of History NSW and the Aboriginal Languages Trust NSW. The First Nations Community Access to Archives project aims to improve access for First Nations people to important archival material about culture, kinship, stories and languages within the State Archives Collection.

Material will be digitised to improve access to Community and to preserve it well into the future. Preservation standards and specifications for the digitisation phase of the project have been established with accessibility as the vital consideration. A true physical image will allow for language and cultural analysis and sharing and honoring the original record.

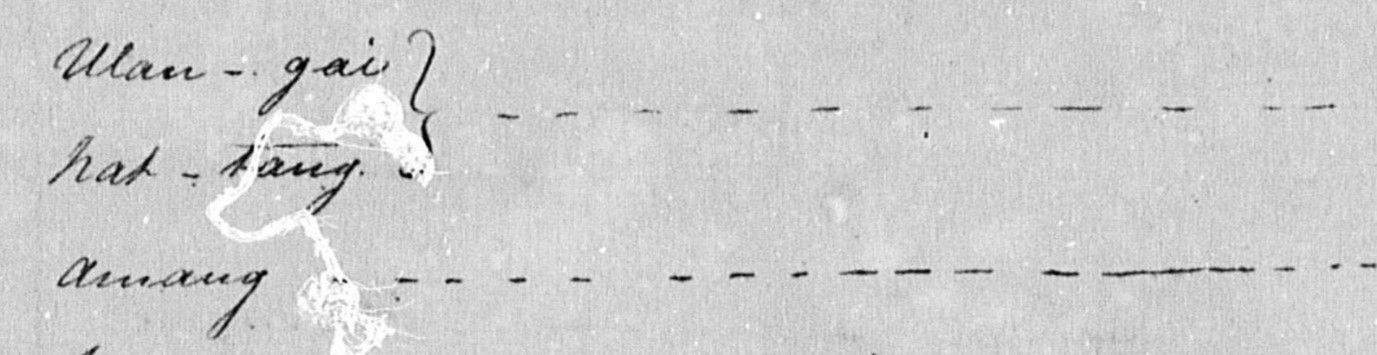

Digital preservation standards have been deeply considered to achieve the best outcomes for community and for language and culture revitalisation. For example, in the language reviatlisation context, diacritics play a significant role in how a word or sound is pronounced. The absence of a simple overdot or circumflex (̂ ) symbol can mean pronouncing that sound/word very differently. If diacritics are not picked up through digitisation this can significantly impact how languages are revitalized.

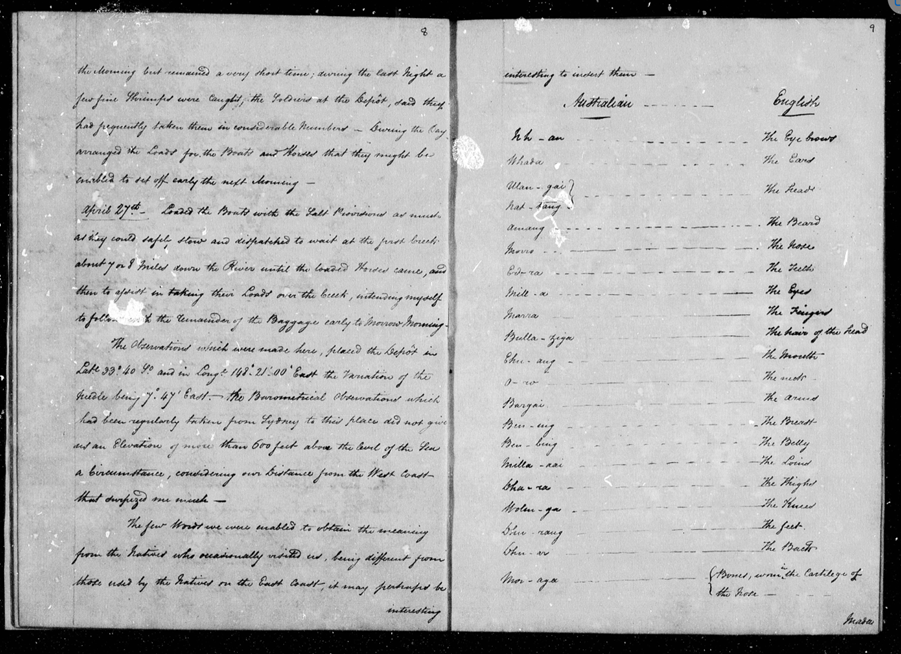

Material currently accessible via our website to community usually consists of poor-quality digitised images from microfilm rather than the original record, for example:

https://records-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=INDEX2359066&vid=61SRA&search_scope=Everything&tab=default_tab&lang=en_US&context=L

MHNSW – StAC: Colonial Secretary; NRS 898, Special bundles. NRS-898-4-[SZ1047] Diary of John Oxley's expedition of discovery of the course of the Lachlan River, 6 Apr-29 Aug 1817, pp 9-10

To take a closer look:

The project team researched preservation standards for paper-based material practiced across institutions in the GLAM sector domestically and internationally. In the past archival preservation standards were set around 600 ppi and are now often based around 400 ppi. This has occurred for many reasons including the resulting size of digitised files impacting network storage and storage costs.

Recognising the importance of materials for community this project has set preservation standards for the digitisation of paper based materials to 600ppi (pixel per inch). Initially the project team undertook test scanning to compare images captured at 400ppi to 600ppi. Resolution, clarity and detail were far superior for the 600ppi images. Many records contain difficult to read cursive scripted handwriting and will often need to be read at a 200% zoom. Tiny details such as diacritics are better copied at the higher 600dpi resolution.

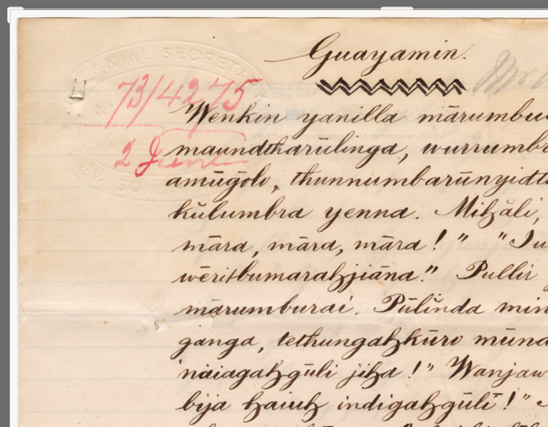

Optics and the physical safety of original records were considerations in the selection of digitisation equipment and how archival material is imaged. The team sought equipment that produces rich, high-quality images with higher bit depth and colour management. ICC colour profiles (ICC profile is a set of data that characterizes a colour) input or output device) are created for each item of equipment to insure appropriate colour management within the project. Set parameters dictate how the material is captured. For example, materials with highly significant language and culture content are captured using a high optic overhead camera capture with work environments setup to capture with no light disruption to the image and scanner with control over the colour space and bit depth. Higher bit depths are also used to capture significant graphic materials – drawings, sketches and photographs.

The image below is example of an item captured by the project:

MHNSW – StAC: Colonial Secretary; NRS 905, Main series of letters received. NRS-905-1-[1/2192]-72/9230. Andrew Mackenzie. Forwarding specimen of Aboriginal Language, 23 Nov 1872 [and translation]

With a focus on sustainability the project will ensure that metadata is embedded at image level to help facilitate the sense-making of the records for First Nations communities now and in the future. It is important for cultural instructions to follow ICIP protocols and in those instances where physical rematriation is not possible, digitising materials to a high preservation standard.

When working with First Nations paper-based materials significant consideration needs to be given to the preservation standards held to by cultural institutions. For the best language and cultural revitalisation outcomes for First Nations communities, preservation standards should remain high. Care should be taken to ensure that resulting images are clear and true to the physical record to allow for interrogation and analysis of the image and its contents in a meaningful way.

References

Baker AG, Tur SU, Blanch FR, Harkin N (2020) Repatriating love to our ancestors. In: Fforde C, McKeown C, Keeler H (eds) The Routledge Companion to Indigenous Repatriation: 854–873. Routledge, Abingdon.