Justine Provino just completed a PhD in English at the University of Cambridge and Dr. Leontien Talboom is a technical analyst at Cambridge University Libraries

This blog post highlights the collaboration between the Cambridge University Library (CUL) Transfer Service and a PhD research project on Agrippa (a book of the dead) (1992). The joint work of the writer William Gibson, the artist Dennis Ashbaugh and the publisher Kevin Begos Jr, Agrippa is an artist’s book made to self-destruct both in analogue – with disappearing images by Ashbaugh – and in digital – with a poem by Gibson located on a floppy disk only readable once. This post focuses on the access to the digital element of Agrippa, Gibson’s poem on a floppy disk, and it brings to the fore a case study of the multiple uses that can be made of disk images, in libraries.

Following a description of what is the self-destructive book Agrippa and how the publishing project came to be, this post is written as a two-voice narrative, first from Justine’s perspective and then from Leontien’s perspective. The aim of the authors is here to emphasise the importance of the help provided by digital preservation specialists to researchers in the library when it comes to connecting (human) readers with early digital texts. In a joint conclusion, the authors reflect on what they learnt from their collaboration.

Agrippa (a book of the dead)

Agrippa (a book of the dead) was published in 1992 as the result of the collaboration between the publisher Kevin Begos Jr, the writer William Gibson and the artist Dennis Ashbaugh. It is an artist’s book that comes in a fibreglass presentation box, mimicking a model of an early twentieth century photo-album labelled ‘Agrippa’ by the Kodak brand. Once opened, the ‘album-box’ reveals to house a cloth-covered book titled Agrippa (a book of the dead) within which can be found printed images by visual artist Dennis Ashbaugh and a 3.5-inch diskette with digital poem by cult science-fiction author William Gibson. The latter’s work is a poem that evokes memories of the writer’s relatives, now dead, and recollected by Gibson as he narrates in the poem his experience of leafing through an old family photo-album labelled ‘Agrippa’, in his family home of Virginia.

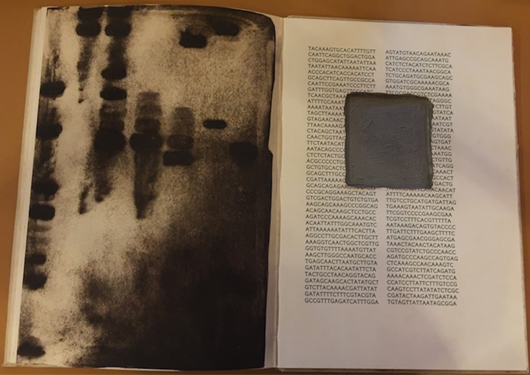

The images by Ashbaugh illustrate the souvenirs of Gibson in the form of print reproductions of vintage advertisements matching the time-period evoked by Gibson in his poem. But Ashbaugh’s work also addresses itself to a scientific question pressing at the time of the making of Agrippa in the early 1990s: the mutation of the DNA. The vintage advertisements are only the top layer of a two-layer print, which on its bottom represents, in aquatint, the autoradiograph (an X-ray image of the DNA pattern) of the genome of the fruit fly. This DNA pattern is also translated in print on the pages facing Ashbaugh’s images, in the recognisable series of letters that constitute anyone’s DNA: A, C, T, G, in this instance said to be ordered so as to read as the DNA sequence of the fruit fly. Agrippa comes in two editions, a deluxe and a small edition. The exact number of copies produced per edition is unknown but it is thought that very few copies were produced, nine of which are currently in public collections (click on the link for a hybrid book tour of these copies of Agrippa).

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Rec. b.38, Agrippa (a book of the dead) (Gibson/Ashbaugh/Begos Jr, 1992), deluxe edition copy ‘Archive I’: book opening showing Ashbaugh’s aquatint representation of DNA autoradiograph (no vintage advertisement printed on top) and the emplacement for the diskette within the printed DNA text.

Agrippa is an artist’s book which means that it materially embraces the literary and visual themes of disappearing memories and scientific and technological changes (recombination of the genome, photographs, digital taking over prints in the written world) evoked by Gibson and Ashbaugh in their respective works. Initially intended to disappear when exposed to light, the images by Ashbaugh prove to disappear through their printing technique. Printed with an unfixed toner ink, the prints offset over time on the adjacent page and as readers leaf through the pages of the book and involuntarily (or voluntarily) collect ink pigments on their fingers. As for Gibson’s poem on the diskette it was long reputed to be encrypted on a programme that would self-destruct after being read once. In 2012, Information Scientist Quinn DuPont launched a contest to crack the ‘Agrippa Code’ whose results showed exactly how the poem is programmed to auto-scroll (without any possibility to stop its reading following its launch) and immediately after how it is set to auto-lock within the diskette, leaving the (human and machine) readers with the impossibility to access the text again. The results of the contest are available in an article published by DuPont and also reproduced via The Agrippa Files, a scholarly website and ‘online archive’ dedicated to Agrippa and created in 2005 by English scholar Alan Liu and his team of researchers at the University of California Santa Barbara (UCSB).

These two particular examples of the academic research that emerged from Agrippa outline just how much, since its making in 1992, the notion of a self-destructive book has and continues to trigger readers’ relationship to Agrippa, and the wider notion of access to and ownership of books by private collectors, curators, conservators, digital humanists and librarians. What does it mean to imprint our ownership of a book on its materiality (leaving finger marks on pages or corrupting a digital text when reading it even once)? Agrippa brings at face value how we wear out books in the process of reading them and sometimes how we read them to death… of their materials (detached covers, loose leaves, electronic book dead battery). And Agrippa asks: what is the role of the library, an institution where books are preserved for the greater mission of disseminating knowledge to all, when it comes to a book that threatens to self-destruct in the act of accessing its content? How can Agrippa be read and researched in libraries when the book is advertised as bibliocidal? The next part of this post focuses on reading and researching the digital element of Agrippa – Gibson’s poem on a diskette – in the context of its librarianship.

How to read a self-destructive poem in libraries? (Justine’s perspective)

In my thesis, I address how the library as a cultural heritage institution puts together an array of policies and collection care procedures to mediate as much as ringfence the ‘hands-on’ relationship of the readers to the materiality of books, whether analogue or digital. For instance, libraries tend to prevent access to an analogue book when it is deemed ‘fragile’, showing signs of auto-decay (such as brittle pages, for example), or too rare to be handled repeatedly. Instead, libraries redeem their compliant readers by pointing them towards a readily accessible digitised version or a digital surrogate of such books on the institution’s website. But digital versions of analogue books are not the only form of digital books that exist in libraries. There is also a growing number of born-digital books, among which early electronic texts, no more than thirty-year old, which too have proved to be put at arm’s length of their (human and machine) readers due their material fragility. The digital carriers for these early electronic texts may have become obsolete and the library might also be lacking the appropriate reading machine to read these digital artefacts. My PhD thesis is based on the case study of the self-destructive book Agrippa (a book of the dead) for which I provide a survey of the different means of access to the poem by William Gibson, an electronic work of literature located on a 1992 floppy disk. How can we read Agrippa today when its reading is advertised as self-destructive and when there are no more 1992 computers at hand in the reading room of a library?

In libraries, Agrippa is recognised as a rare book, this means that it is located in a ‘closed stack’ and that its consultation is automatically subject to a special permission from the library staff. Only seven public institutions worldwide hold a copy of Agrippa or related materials. The main resources for my thesis have been a deluxe- and a small edition copy of Agrippa and the archive on the book project which its publisher, Kevin Begos Jr, donated to the Bodleian in 2011. Among the institutions to have a copy of Agrippa, only four of them own a copy with a diskette (the National Art Library at the Victoria & Albert Museum, the New York Public Library, the Yale University Art Gallery, The Zhang Legacy Collections Center at Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo). Among those four libraries, none of them have read the disk or are currently allowing their readers to access the poem said to be located on their diskettes. This means that, when library staff grant readers special access to the analogue book (presentation box, Ashbaugh’s images and printed DNA text) located in their collection, the digital part of the book – the floppy disk with Gibson’s poem on it – remains inaccessible in the reading room.

The auto-locking programme that regulates the one-time access to Gibson’s poem on the diskette has led to the digital book in Agrippa becoming the least accessible part of the book in libraries. Should libraries change their mind and decide to provide their readers with access to the poem, a 1992 diskette has long become an obsolete storage device for a digital text. To read the diskette in libraries today, this would require the use of a transfer device, preventing the magnetic tape of the disk has not degraded too far after thirty years and that its data are not corrupted. In this context of custodianship of the self-destructive book in the institution of the library, the content of Gibson’s poem could have remained an enigma, but for the happy few private collectors who, having purchased a copy of Agrippa, may have been willing to read the text and immediately after lose access to it. (To date, my research shows that I have not encountered such a collector, but I am always on the lookout for more collectors.) Against all odds, since 1992, Gibson’s poem has been the most accessible part of the book, not in the reading room of a library but… on the Internet!

On 9 December 1992, the night of Agrippa’s release – a launch event called ‘The Transmission’ – at the Americas Society in New York City, Agrippa was hacked. The content of the diskette projected on a screen at the launch event was secretly recorded on a VHS tape. Immediately after it was retyped and posted on bulletin board systems, revealing to be a 305-line autobiographical poem by Wiliam Gibson. Today, the content of this tape is accessible (with permission of the writer, the publisher and the hackers) on the YouTube account of English scholar Matthew G. Kirschenbaum and via the scholarly website ‘The Agrippa Files’ launched by Alan Liu and his team at UCSB in 2005. About a decade after Agrippa was hacked, in 2008, another digital surrogate of the poem emerged on the Internet. This time it took the form of an emulation of the content of a diskette, which was part of a copy of Agrippa that then belonged to private collector Allan Chasanoff and whose copy is now at Yale University Art Gallery. Liu and Kirschenbaum teamed with Doug Reside at the University of Maryland to create a disk image of the content of the diskette located in Chasanoff’s copy without reading the said diskette. The result of their experiment – and a link to a video of the emulation of the poem posted also on Kirschenbaum’s YouTube account – are available on The Agrippa Files.

In my thesis, I highlight how, to access Gibson’s poem, readers have and continue to rely on the digital surrogates available on the Internet since 1992: BBS file, video of the hack of 1992, video of the 2008 emulation of the poem. Meanwhile, libraries have kept in their collections the Agrippa diskettes as untouched relics of the nineties. My PhD questions how viable is this redirection towards endless digital surrogates in the longue durée? How can libraries fight both in-house digital obsolescence of their collections, such as issues of transfer of data, and potential exterior threat of a hack on their institution, while also addressing their readers’ need for access to early digital material texts? With the floppy disk at the heart of Agrippa, my thesis is interested in how, to date, access to the poem by William Gibson can (not) exist in the library, without the support of the Internet.

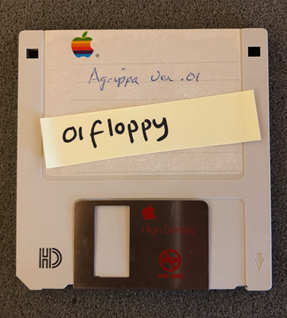

The Bodleian Library does not own a diskette in either of its copies of the book but the library owns a diskette located within its publisher’s archive. During my research, I found an Apple Macintosh diskette from the nineties in Begos’s archive. The description on the Bodleian Archives and Manuscripts webpage informed me that this diskette is a ‘digital material [that] is not currently available’ for consultation and that its access status is: ‘closed’ (inaccessible). The library staff agreed to let me have access to this digital artefact under the condition that I, as a reader, will not read the diskette in the reading room. There I was, in the reading room, faced with a diskette which I could not read but which to me looked like a book. On its outside, the diskette looked pristine. As can be found on a book cover, on the diskette’s recto there is a finishing element: a sticky label with a recognizable rainbow-striped apple ornament from the Apple MacIntosh computer brand in the 1990s (see image below). This label bears only a brief inscription or ‘book title’ inscribed in blue pencil ink: ‘vers. 1’ (a short for ‘version 1’ one is to assume). Altogether, this plasticky cover supposedly encloses a text programmed to be read only once on its metal sectors: the poem by William Gibson. But how could I know for certain that what I was looking at was possibly a ‘version 1’ of the poem by Gibson, whose digital surrogates populated the Internet? And what could this archival diskette tell me of the poem’s publishing process and the auto-locking programme supporting it? Did this diskette differ from the finished published version available via the 1992 video of the hack or the video of the 2008 emulation on the Internet?

Discussions with Head of Archives and Manuscripts Susan Thomas and Senior Archivist Matthew Neely at the Bodleian revealed that when the diskette arrived at the Bodleian they extracted the raw data on this diskette. But it appeared to be corrupted. This is why, in 2024, I turned to Leontien Talboom to see if the transfer service at the Cambridge University Library could shed new light on the corruption of the diskette and help me to (re)connect the content of the diskette physically held in the Bodleian’s archive, with the poem by Gibson that has been circulating on the Internet these past three decades. The Bodleian agreed to share the data they had extracted from their diskette with Leontien at CUL. This led to our collaboration and the emergence of a new set of questions on the self-destructive book in its context of librarianship: over thirty years after its publication, could we reconcile the scope of the diskette – a reading device – with its present repository: a library? Could we finally be able to provide readers in the library with access to the content of Agrippa’s diskette without relying on the institution’s access to the Internet? And how what we might discover on ‘version 1’ may in turn inform our understanding of the digital versions of the poem currently circulating on the Internet?

Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Digital 27 = RES, floppy disk currently restricted from access

Reading the 1992 Bodleian’s diskette at Cambridge University Library (Leontien’s perspective)

We met up for a number of sessions to look at the disk image created by the Bodleian of version 1. Our main objective was to see what information we could get from this disk image and see if it differed from the disk image which is available on The Agrippa Files website.

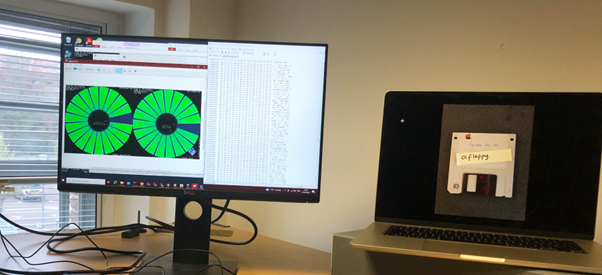

When Justine contacted me I was surprised by her research questions. Normally when I am requested to help with floppy disks the focus is on emulating the carriers and showcasing it in the environment that the material was created in. However, Justine was not necessarily interested in this as her research focused on other elements on the diskette; creation dates, the encoding and formatting of the disk, the differences of the diskettes on a hex level, etc. To inspect these types of elements a number of digital forensics tools were used. The disk image was provided by the Bodleian and we knew that it had been created using a Kryoflux, which is a specific type of floppy controller, and that there was corruption on the disk. Our first step was therefore to see if we could open the files in the HxC floppy emulator.

Our set-up in the lab, looking at the results on the HxC floppy emulator.

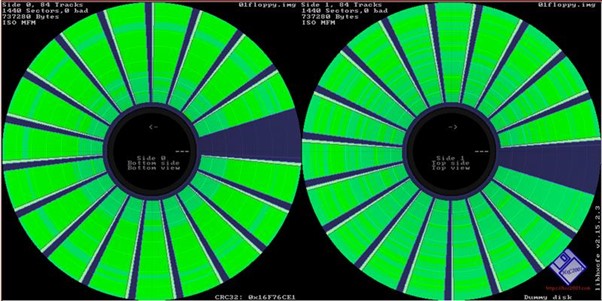

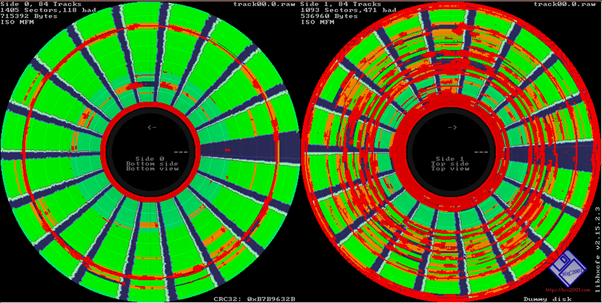

There were two types of files provided to us, both gave slightly different results in the floppy emulator. The first one being a .img file, the other one being the raw flux stream (.RAW). The .img does not seem to see any problems or bad sectors, but the bad sectors are written over with empty file parts. The second, RAW floppy image gives a better idea of the state of the disk, with bad sectors (see images below).

.img file rendered in HxC Floppy Emulator, bad sectors are not showing up here because these have been overwritten with empty data.

.RAW flux stream rendered in HcX Floppy Emulator, bad sectors are prominent on this version and is in line with what the Bodleian mentioned when providing access to these files.

The corruption on the disk will make it difficult for us to compare the Bodleian disk to the one available on the Agrippa Files website. However, what we can conclude from looking at the disk image on this emulator is that the formatting of the disk is the exact same for both the Bodleian and The Agrippa Files one. Both are a 1.44MB floppy disk, with 80 tracks (84 showing up in the emulator, but the first few do not contain actual data. The header, the beginning of the disk, does not start until later) and 18 sectors with MFM Encoding, which corresponds with the Apple II formatting.

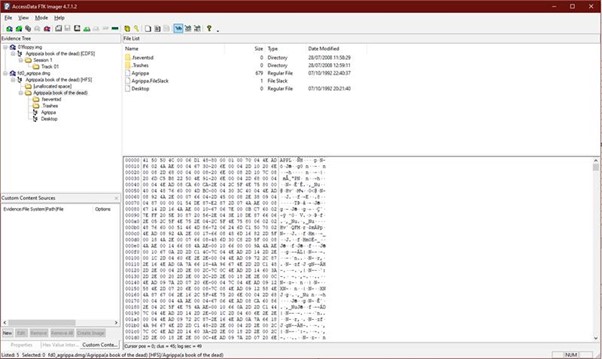

The other tool that we looked at was FTK Imager, which is a forensic tool to look at files. It is different from the floppy emulator, as it will not give a disk overview, but a more detailed overview of the files on the disk. FTK Imager is openly available, the rest of the suite is proprietary. For our analysis, FTK Imager gives us a good overview of the disk that we are looking at.

The image below shows both of the disk images opened in the FTK Imager tool. It is possible to browse The Agrippa Files one, but the one provided by the Bodleian only gives a stream of data. FTK is also not able to open RAW flux streams, as these have not been formatted. FTK therefore has given us an overview, but no further interesting discoveries such as is possible for The Agrippa Files diskette, which includes dates and an overview of the files.

Image showing both the diskettes opened in FTK Imager. The top one (01floppy.img) is the one provided by the Bodleian, the one below it (fd0_agrippa.dmg) is the Agrippa Files diskette. This diskette is also opened in the right hand panel, showcasing the same dates highlighted in the technical analysis of the diskette.

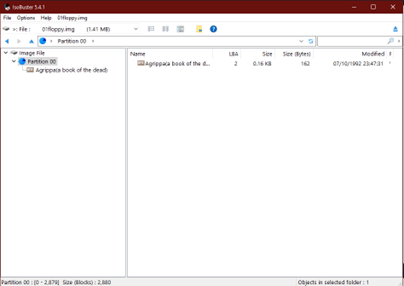

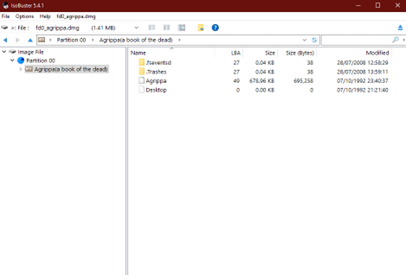

These two images highlight the disk images open in IsoBuster. This tool gives us a bit more insight on dates, as it provides a date for the Bodleian diskette. This seems to have been modified 7 minutes (23:47) after the one of the Agrippa Files website (23:40).

As a next step, we looked at the disk image in a tool called IsoBuster. This software has similar possibilities to the FTK Imager tool. However, this one showcased to us that the file system is HFS. This was expected, as this is the proprietary file system used by Apple at the time. Sadly, we could not do anything further with it within this tool, we are assuming this is due to the corruption on the Bodleian diskette. However, we did spot an interesting date here. The date is very similar to the one on The Agrippa Files diskette, but is seven minutes later.

As a last step we looked at the Bodleian diskette on a Hex Editor and compared them to The Agrippa Files diskette. Sadly to do a proper comparison, more time would be needed. It was also made more complicated due to the fact that the Bodleian file is severely corrupted, making comparison difficult.

There are certainly similarities between the two disk images, we have been able to conclude that they have been created with the same formatting and have the same file system. Further analysis of the actual files is difficult at this point due to the corruption on the Bodleian disk image. However, we did discover a date – 7 October 1992 at 23:47:31 – that is very close to the date – 7 October 1992 at 23:40:37 – on The Agrippa Files website. This date inscribes the diskette’s programming as part of the publishing process that led to the launch event of Agrippa and its hack on 9 December 1992. Further investigation could be done with more specific Apple tools, including ResEdit, DiskJockey and Applesauce.

Conclusion

Our work together has highlighted that there is more to discover and can be done around the diskettes produced as part of the copies of Agrippa. It showcases the useful collaboration between digital preservation and analogue conservation of material texts in libraries so as to better understand the programming of a text beyond its finished (or final, in the case of Agrippa) appearance on a computer screen. It also highlights the need for readers to gain direct access to early digital texts in the reading room of a library.

In conclusion, disk images are key for preserving the content of early digital media like floppy disks, especially when it comes to emulation. However, focusing solely on the data these images hold overlooks the valuable research potential of the disk image itself. Just as scholars analyse the physical traits of printed books—paper, bindings, and watermarks—researchers of digital media can glean important insights from the ‘material characteristics’ of diskettes, such as their format, construction, and even the unique quirks of how they were created. Preserving this information adds a new dimension to the study of early digital books and other media, making it clear that both the digital and physical aspects of these artefacts matter.

Furthermore, the process of creating disk images can vary, depending on the machines, tools, and settings used. These technical details are often just as important as the files contained on the disk itself, as they can impact what a researcher is able to discover. Emulation, while valuable for replicating original environments, often abstracts away this vital information. Without a record of how these images were made, researchers risk missing key pieces of the puzzle. The physical artefact can provide context that an emulation cannot—details like formatting, irregularities, or even specific hardware quirks that could lead to different research outcomes.

Ultimately, while emulation provides powerful tools for exploring the contents of disk images, it is not the only approach researchers need or want. To fully understand early digital media, scholars require access not only to the data but also to the physical diskettes and the history of how these disk images were created. Bridging the gap between digital preservation specialists and bibliographic researchers is crucial to supporting future work in this field and to the mission of the library in providing access to knowledge for all. Preserving these artefacts holistically—both as digital and physical objects—ensures that their full research potential is realised.

We wish to thank the Bodleian Library for agreeing to share the data extracted from their diskette and images of Agrippa and its archival diskette with us.

About the authors

Justine Provino just completed a PhD in English at the University of Cambridge. Based on the case study of the self-destructive artist’s book ‘Agrippa (a book of the dead)’ (1992), Justine’s research addresses how library policies and collection care procedures mediate as much as ringfence readers’ access to books in libraries. This PhD is an Arts and Humanities Research Council Collaborative Doctoral Award with the Bodleian Library, where are housed two copies of ‘Agrippa’ and its publisher’s archive. Justine is a book conservator and prior to her PhD she held positions at the Bodleian Library and the Morgan Library & Museum.

Dr Leontien Talboom is a technical analyst at Cambridge University Libraries, she looks after the Transfer Service and spends most of her time transferring material from obsolete media. This year she will also be working on the Future Nostalgia project, funded by the British Academy. This work will look into safeguarding knowledge on floppy disks.