Shira Peltzman is Digital Archivist for the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Library Special Collections

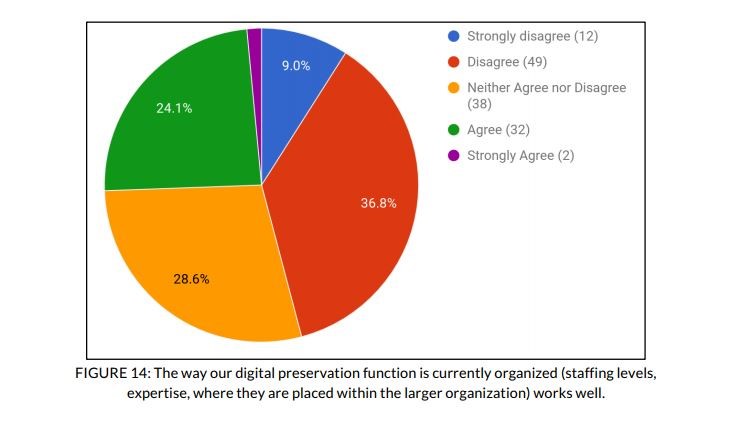

Buried in the recently published findings from the 2017 NDSA Staffing Survey is evidence of a growing discontent among practitioners with regard to their organization’s approach to digital preservation. The survey asks respondents whether or not they agreed with the following statement: “The way our digital preservation function is currently organized (staffing levels, expertise, where they are placed within the larger organization) works well.” Of the 133 people who took the survey, 61 of them, or roughly 46%, either disagreed or strongly disagreed with that statement.

“Q16 - The way our digital preservation function is currently organized (staffing levels, expertise, where they are placed within the larger organization) works well. [133 respondents]”] Taken from “Staffing for Effective Digital Preservation 2017 An NDSA Report”: http://ndsa.org/documents/Report_2017DigitalPreservationStaffingSurvey.pdf

To say that those numbers aren’t great would be an understatement. To make matters even worse, they represent an increase from the 2012 iteration of the survey, in which 34% of participants reported that they were unsatisfied with how things were organized.

It’s difficult to know what to make of these results. The survey instrument did not include any follow-up questions to probe precisely why institutions are so dissatisfied with the way the digital preservation function is organized within their institution. While the high and rising dissatisfaction among digital preservation practitioners indicates that there is a problem, its root remains unknown.

Until this issue is studied in greater depth, the best that we can do is rely on anecdotal evidence to guide our assumptions about its underlying cause. This is an especially tricky task given that the survey defines ‘organization’ quite broadly in a confluence of both qualitative and quantitative terms. Still, reading this report immediately brought to mind a panel organized by the DPC’s own William Kilbride at this year’s PASIG conference in Oxford, UK. At one point during the discussion, William administered an impromptu straw poll. “What stops you today from putting your digital preservation plan into action: money, technology, or politics?”, he asked the audience.

The number of hands raised for option C was overwhelming; ‘money’ and ‘technology’ paled in comparison. Perhaps the skeptics or statisticians among us might make the argument that this could simply be a case of selection bias--that the reason ‘politics’ received so many votes could be due to the self-selecting nature of a conference geared towards digital preservation practitioners.

Yes, perhaps.

But in my experience, the issue of politics functioning as a roadblock to preservation is both universal and pervasive. It affects organizations small and large, public and private, well-funded and under-resourced. Whether the politics are inter-personal or departmental, intra-institutional, or even national or international in scope, the fact remains that all too often, digital preservation activities are slowed or altogether impeded by conflict among stakeholders that is either real or imagined, and which has little to do with the resources or technology at our disposal.

The results of William’s survey offer, at the very least, some clues into the landscape of the overall unhappiness recorded in the survey. But could there be a link between the substantial majority of PASIG attendees who named ‘politics’ as being the greatest roadblock to their work and the the rising dissatisfaction among practitioners recorded in the NDSA Staffing Survey? The possibility is tantalizing.

Obviously a straw poll is a far cry from the rigorous data collection that this subject demands, and much deeper study is necessary before any linkage could be officially established between the poll results and the low overall satisfaction recorded in the NDSA Staffing Survey. But I don’t think it’s a stretch of the imagination to see a potential point of connection between the two data points. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that we as a profession owe it to ourselves to consider whether this might be the case.

It’s difficult to solve a problem if you don’t know what’s wrong. The data clearly indicates that something is amiss. It is up to us to scrutinize and unpack the dissatisfaction expressed by survey participants, and put in the legwork necessary to identify its root cause. The future of our profession may depend on it.