Hernán Cabrera Pichuante es Jefe de Proyectos Técnicos del Proyecto de Modernización de Archivos Nacionales de Chile (National Archives of Chile)

[English version follows]

Estamos llenos de información almacenada y muchos de mis conocidos en el área de TI insisten en que la copia no solo es segura, sino que, prácticamente eterna.

Es frecuente ver como las políticas de respaldo de los activos tecnológicos llenan bodegas con cintas magnéticas creadas en modernos sistemas automáticos de respaldo.

Es frecuente ver como una y otra vez, al querer recuperar algo la respuesta es: ¿te acuerdas de más o menos de que fecha es lo que me pides?

Es más frecuente aún, que luego de un par de días de búsqueda, la cinta se encuentre y lo que sigue es que estas, por lo general, contienen más de una versión del mismo documento y nos preguntamos …y ¿cuál de todos estos documentos es el que busco?

Y lo que ocurre a menudo, es que lo recuperado requiere de un software especial para ser leído. Software que nadie sabe dónde está y de saberlo, no se puede correr pues se desconoce cómo hacerlo.

Y ocurre, de tanto en tanto, que lo recuperado no se puede rescatar pues algo se corrompió.

Y lo que ocurre siempre, pero siempre, es que todo lo anterior está normalizado y es la forma en que el mundo pareciera funcionar: No te preocupes, yo lo respaldo y lo vuelvo a respaldar y cuando me lo pidas tal vez lo encuentre y tal vez te sirva.

Pocos han entendido que, la preservación es un conjunto de actividades que se deben realizar de forma sistemática, documentada y revisada. Lo normal, es entender que lo que queda obsoleto se elimina o se ignora y se deja languidecer en una cinta que con el tiempo se volverá ilegible. Por eso, algo que no falla es contar a todos esos sufridos personajes encargados de respaldo, que la preservación existe, que es un proceso y que se ha estado mejorando en los últimos 20 años o más.

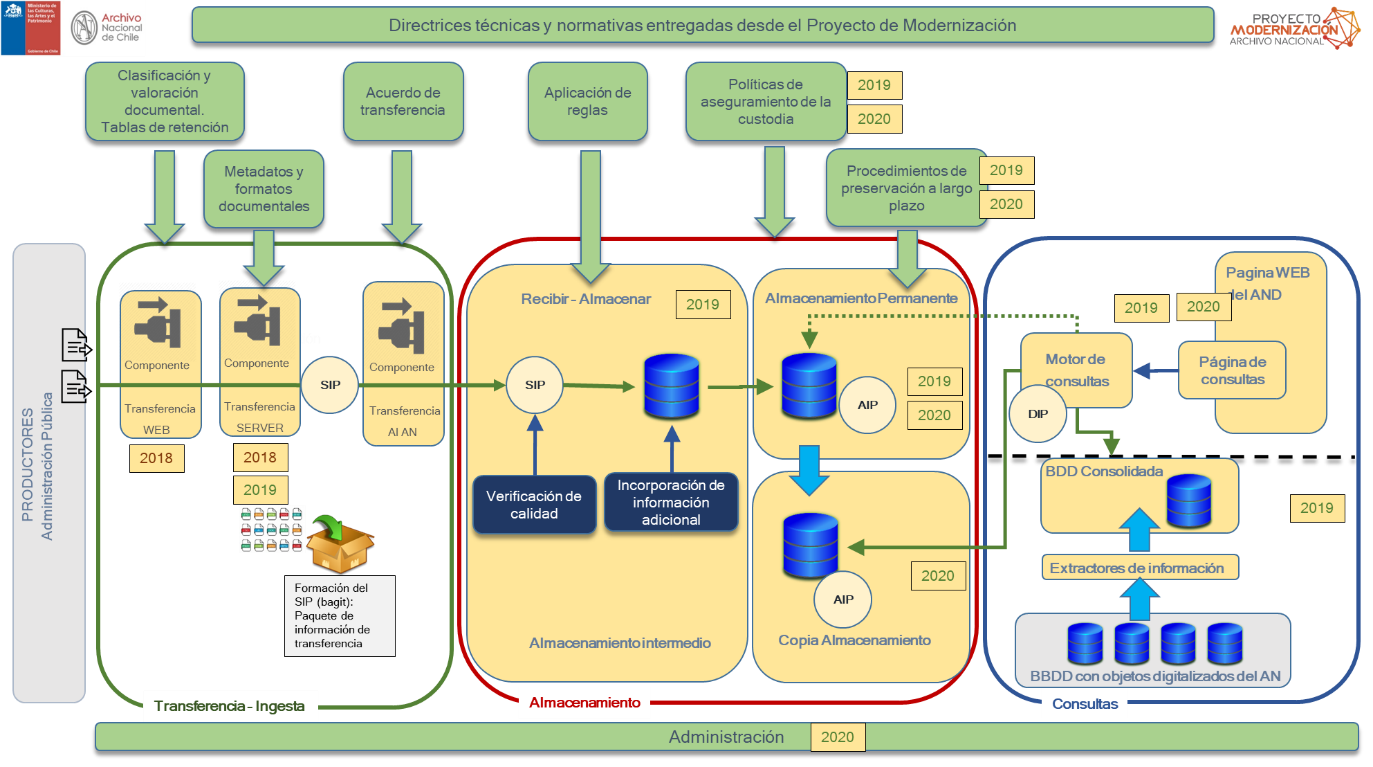

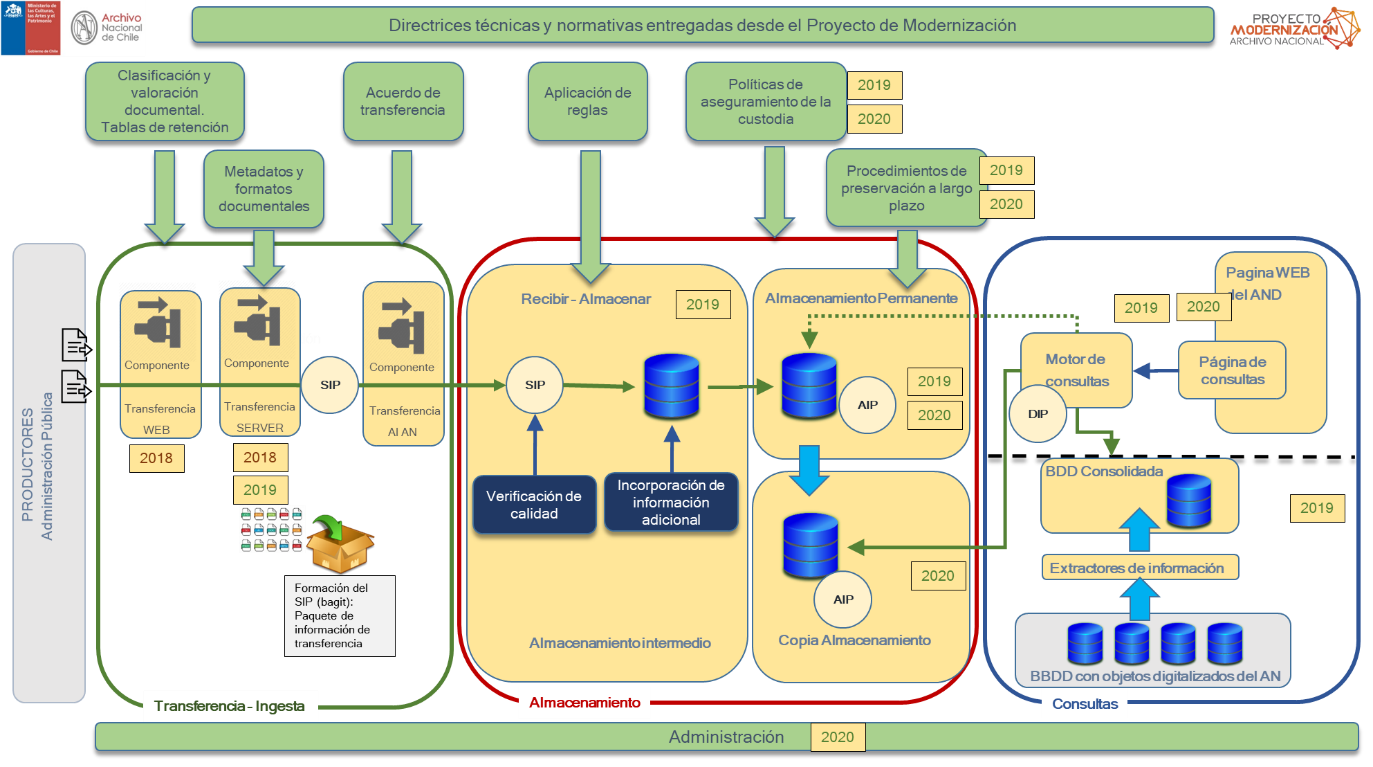

Ahora estamos a mitad de camino de un proyecto que tiene como misión implementar OAIS en el Archivo Nacional de Chile. En este tiempo las expectativas de las instituciones públicas han migrado de poder transferir electrónicamente series documentales al Archivo Nacional, a clasificar y valorar series documentales para su conservación a largo plazo, pero ha sido en los últimos meses en que un mensaje implantado tiempo atrás, por fin ha cuajado: ¿Cómo recuperaremos esa información en 100 años más?

Como proyecto de Modernización, estamos en el desafío tecnológico de la implementación de mecanismos, plataformas, sistemas y procedimientos que permitan la preservación de expedientes electrónicos. Pero junto a ese desafío ya mayor, hemos entendido en este tiempo que parte importante del proceso es sacar del inconsciente colectivo que existe una mano mágica que se encarga de que las cosas estén siempre disponibles e incorruptibles (el mágico respaldo) y junto con ello, remover esa idea persistente de que conservarlo todo es posible pues el espacio de almacenamiento es “barato”. Esto último, si bien es real en cuanto al valor por bit, en los esquemas de preservación es contra intuitivo explicar que preservar algo encarece ese mismo bit a medida que pasa el tiempo.

A la fecha sabemos que hemos perdido información que no sabemos si es valiosa o no (una pequeña apreciación, considero que algo que está almacenado “en alguna parte” pero no soy capaz de recuperarlo en forma oportuna, también es algo que se ha perdido) y ahora podemos estar a punto de pretender que todo es valioso “por si acaso”. Lo difícil ahora es responder a la pregunta: ¿Qué está en peligro exactamente? Este fenómeno es producto de no tener determinado el valor de lo que se está generando, pero a la vez podemos entender que en las Instituciones Públicas de cualquier nación del mundo se han tomado decisiones que quedan documentadas, eso está en peligro y también está en peligro el fundamento documentado que permitió tomar la decisión. Por lo tanto, estamos perdiendo el registro de nuestras acciones como Nación y la justificación de esas acciones y con ello perdemos la evidencia de que lo hecho ha sido coherente, correcto en su momento y probo. La conclusión final es que estamos perdiendo credibilidad y con ello la confianza de la ciudadanía en la gestión de su propio Estado.

A fines del año 2020 tendremos la plataforma tecnológica, en una primera versión, preparada para recibir transferencias electrónicas desde las Instituciones Públicas. Ese día, entendemos todos en el equipo de proyecto, será el día inicial de la preservación, el camino recién comenzará y tendremos la gran responsabilidad de entregar, junto con la plataforma tecnológica y los procedimientos técnicos, el desafío de la conservación a largo plazo y con ello incrementar la confianza que tiene la ciudadanía sobre las decisiones que toma el Estado.

Loss of credibility

Hernán Cabrera Pichuante is the Technical Project Manager of the Modernization Project of the National Archives of Chile

Our archives are full of stored information and many of my acquaintances in the field of IT insist that copies are not just secure, but practically ever-lasting.

Policies on backing up technological assets often result in stores that are full of magnetic tapes created on modern automatic back-up systems.

Time and again when we want to retrieve something, the answer is, “Do you know roughly when it dates from?”

What is even more common, after a couple of days searching, is that the tapes are found and contain more than one version of the same document and we are left wondering, “Now, which of all these documents is the one I was looking for?”

And what frequently happens is that the file we have retrieved needs a special kind of software to be able to read it; software that nobody knows where it is and even if they did, they couldn’t use it because nobody knows how.

And what happens fairly often is that the file we retrieved can’t be recovered because something in it has corrupted.

And what always, and I mean always, happens is that all of the above has become normal and is the way in which the world seems to work. Don’t worry, I’ll back it up and I’ll back it up again and when you ask me for it, I might be able to find it and it might work.

Not many people have understood that preservation is a series of activities that must be carried out systematically, documented and reviewed. It tends to be understood that anything that becomes obsolete will be thrown away or overlooked and left to languish on a tape that, over time, will become unreadable. That's why a fail-safe method is to tell all those long-suffering people with responsibility for backing up data that preservation exists, that it is a process and that it has been improving over the past 20 years or more.

We are now in the middle of a project whose mission is to implement OAIS in Chile’s National Archive. During this time, the expectations of public institutions have gone from the ability to transfer documentary collections electronically to the National Archive, to classifying and evaluating documentary collections for their long-term conservation. However, it is only in recent months that the message, communicated some time ago, has finally been received: how will we retrieve this information in 100 years’ time?

As a modernisation project, we are facing the technological challenge of implementing mechanisms, platforms, systems and procedures for the preservation of electronic files. But together with this (now large) challenge, over time we have come to understand that an important part of the process is ridding the collective unconscious of the idea that there is a magical hand making sure that things are always available and incorruptible (a magical back-up) and, together with this, removing the persistent idea that it is possible to conserve it all because storage space is “cheap”. Regarding the latter, although this is true in terms of a value per bit, in preservation plans it is counter-intuitive to explain that preserving something will make that same bit more expensive over time.

To date, we know that we have lost information that may or may not have been valuable (a small observation: I consider something that is stored “somewhere” and cannot be retrieved when requested, to be lost too) and now we may be about to start claiming that everything is of value “just in case”. The difficult thing now is answering the question, what exactly is at risk? This phenomenon is the result of not having determined the value of the things being generated, but at the same time we can understand that in the public institutions of any country in the world, decisions have been taken which have been documented. This is what is at risk, as is the documented basis for the taking of those decisions. The result is that we are losing the record of our actions as a nation and the justification behind those actions, and with it we are losing the evidence that what took place was consistent, correct at the time and proper. The final conclusion is that we are losing credibility, along with the trust of the general public in their country’s public administration.

At the end of 2020 we will have the first version of a technological platform which is capable of receiving electronic transfers from public institutions. That day, as all of us on the project team understand, will be the first day of preservation. The journey will only just have begun and we will have the great responsibility of delivering, together with the technological platform and the technical procedures, the challenge of long-term conservation and with it, of increasing the trust of the public in the decisions taken by the State.