Neil Beagrie is Director of Consultancy at Charles Beagrie Ltd

Illustration by Jørgen Stamp digitalbevaring.dk CC BY 2.5 Denmark

Traditionally the major challenge in digital preservation has been seen to be technology obsolesence. However, arguably the organisational challenges, particularly funding (and advocacy for funding), have proved to be much more significant over time.

In recent years an increasing number of community efforts have focussed on helping organisations to identify benefits and write a business case for digital preservation. The Keeping Research Data Safe (KRDS) Digital Preservation Benefits Analysis Tools and the Digital Preservation Business Case Toolkit are good examples.

Most organisations require a business case for major funding projects. This will outline what resources are required, what the resource will be used to achieve, and how this new investment will benefit the organisation.

It is seen as good practice to have actively considered a number of alternative options to the preferred one that you have put forward. One of the options normally recommended for inclusion in a business case is that of doing nothing and its consequences (“the costs of inaction”).

This blog suggests how research on “the costs of inaction” might contribute successfully to advocacy and business cases for digital preservation.

Although it will be of value to all repositories, it will be particularly pertinent for new and emerging repositories. New and emerging services may face particular challenges because digital preservation is a long-term activity: collections are usually appreciating assets - returns can increase over time as collections reach a critical mass and user awareness of them grows.

For these repositories it is always helpful to consider “the cost of inaction” and the counter-factual position if no repository exists. There are already hidden opportunity costs and negative consequences involved in doing nothing and they can provide a benchmark against which the value of and funding case for new or emerging services can be assessed.

Counter-factual evidence is difficult to gather and this remains an understudied approach. There are a few great examples for other preservation domains (I am a big fan of AVPreserve's Cost of Inaction Calculator for Audio Visual archives and its promotional video) and this video is worth watching to understand underlying principles even if you are not an AV repository.

Another relevant example is from the domain of data archives. A recently completed CESSDA-SaW Cost-Benefit Advocacy Toolkit produced on behalf of the Consortium of European Social Science Data Archives looks at how we might evaluate immature repositories or the case for creating new ones. The Toolkit emphasises the potential importance of thinking counter-factually. What would happen if there was no repository?

There are a small number of studies that have looked at quantifying some of the hidden and opportunity costs, particularly for data archived with individual researchers as opposed to being preserved in a long-term repository.

Illustration Charles Beagrie Ltd ©2017. CC-BY licensed

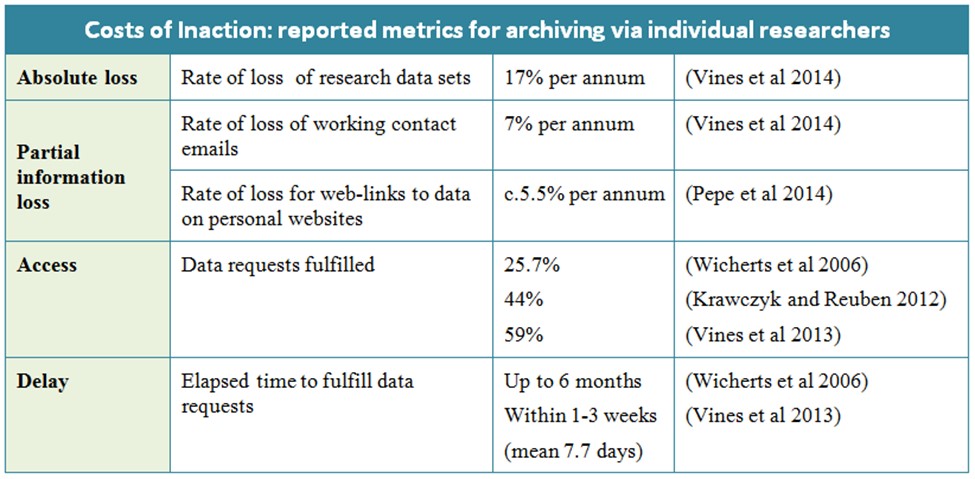

The CESSDA SaW Return on Investment Factsheet in the toolkit pulled together what evidence we have on the counter-factuals for data repositories. These studies are all partial and narrowly focussed. However, they variously consider what happens when research data is archived by individual researchers.

The reported findings are summarised in the table below in terms of total data loss, partial data loss, access (data requests fulfilled), and delay (the elapsed time until requests are fulfilled). The loss of data, loss of access, delays and inefficiencies are in many ways the flip-side of the high efficiencies seen for users of data archives. They are discussed in fuller detail in the Factsheet.

Illustration from Cessda-SaW Return on Investment Factsheet Charles Beagrie Ltd ©2017. CC-BY licensed

These reported metrics are from studies of different disciplines and study dates (and perhaps have differing levels of certainty – absolute loss is a very difficult metric to gather evidence for). However, they contrast sharply with the excellent preservation record, very high fulfilment rates, and rapid online access rates of public data archives in the social sciences. The public data archives also are appreciating as opposed to depreciating assets with improving rather than decreasing trends in value over time.

These studies and results provide an indicator of how valuable more data on the cost of inaction would be to the digital preservation community generally. They also provide pointers to the methodologies that could be used. Feedback from focus groups with key stakeholders of data archives undertaken during production of the toolkit (see the CESSDA SaW D4.9 Cost-benefit Advocacy Toolkit Deliverable Report) certainly suggests how effective data on the costs of inaction could be as a central part of our advocacy and in business cases for digital preservation. It is research I would like to see extended and if you are aware of other examples please let me know.