Elizabeth Kata is Archives Associate for the International Atomic Energy Agency based in Austria

Let’s face it, there are a lot of barriers to preservation, often due to a lack of resources. An institution needs enough staff and sufficient training opportunities for said staff, technical infrastructure, and an institutional commitment to finance preservation measures. When we began examining our digital holdings in 2020, we encountered a variety of barriers, both anticipated and unexpected.

Finding the Unknowns

Our institutional archives has a variety of both born-digital and digitized holdings. While some of these holdings were well described and under basic preservation management, we regularly had the experience of finding a floppy disk or a CD mixed in with paper holdings that were not mentioned in the catalogue descriptions. These digital holdings were doubly at risk: they generally were not backed up and sometimes on obsolete or at-risk media, and they were not described in the catalogue and therefore an unknown resource. Besides listing the already documented digital assets in a digital asset register (using the UK National Archives’ Information Asset Register template), we also sought to identify and describe the “unknowns” – the digital assets stored with paper records.

To do this, we examined our transfer sheets, lists of records which have been transferred to the archives. Up until the mid-aughts, this process was entirely paper-based, and for some material, the transfer sheets represent the most thorough listing of records. We painstakingly analyzed transfers from 1975 to the present, with the justification that there were no known examples of digital material on storage material from before that year. (We did find one or two examples or punch cards or punch tape.) We focused on business units that had an IT-focus or were known to be heavy users of IT-applications. We decided to physically check 175 transfers, which represents about 14% of the overall transfers documented in our catalogue.

I began work on this survey in February 2020 – we all know what additional unexpected challenge arose. Covid-19 changed working arrangements, meaning staff worked partially from home and partially on premises to keep in-person numbers down. Time on-premises was limited and could not always be allotted to the survey. Thus a task that was scheduled for a few months required a year to complete.

We initially captured 120 digital assets in our register, dating from 1986 to the present. Media was found in 22 transfers or about 12.6% of the transfers that we physically examined. Yet out of 105 assets on storage media, only 16 assets (in 11 transfers) were identified by keyword searches (such as “software” or “database”) but had not been previously listed storage media in the descriptive metadata. Based on the limited number identified by keywords, further use of this method applied to a larger number of transfers would not likely significantly increase the amount of digital assets identified. However, digital assets are added to the register whenever found in files: since the completion of the initial survey in March 2021, seven additions assets have been added to the register.

In a follow-up action, we are updating the descriptive metadata in our catalogue to identify the inclusion of storage media, as well as to point to its (new) location, such as on our preservation server. When this has been completed, the digital material in our archival holdings will be easier to find and access, removing one of the barriers for potential users.

Hardware on a Budget

Hardware presented the next preservation barrier – in some cases we did not have the hardware necessary and did not have the budget to acquire it. We set up a basic preservation workbench in Autumn 2019, and we already had external CD/DVD and 3.5” Floppy drives. Through the survey, we found a total of 126 5.25” floppy disks. We decided to acquire the necessary hardware to examine these disks in-house, but that was easier said than done.

5.25" Floppy Disk Drive and FluxEngine in Exposed PC Housing

We looked into a few possibilities, and we chose to build a FluxEngine, a USB / floppy disk interface and accompanying software, which required a little additional work but fit into our budget. First, we acquired a 5.25” floppy drive using a local website for second-hand purchases. We used an older computer for the power source, and then we acquired the parts needed for the FluxEngine. Building the FluxEngine hardware required soldering, but with some assistance, we were able to get it up and running, with our total expenses under 150 EUR. The software documentation might not be as extensive as for other flux solutions, but the designer/writer David Given was responsive when we had questions. This solution worked well for us, and we’d be excited to hear about other preservation practitioners working with this.

The FluxEngine alone could not solve all our hardware woes. We have several JAZ and ZIP disks, as well as mini-data cassettes, which we currently cannot access. Due to the relatively limited number of these media as well as questions about its ultimate retention, we have not tried to acquire the hardware needed. For more difficult to find hardware, it would be great if larger institutions offered assistance in either lending out hardware or providing other assistance for smaller institutions that cannot afford it. This is perhaps a big ask, but it should be in everyone’s interest and would help to break down hardware-related barriers to preservation.

Format Blues

Once I got down to the work of examining disks, I also hit new challenges, chiefly proprietary formats. We have several early databases in dBASE IV, for example, which we could probably get running in an emulation environment. However, as these databases have been successfully migrated to newer formats, the question of resurrecting them is moot. We also encountered several .drw files. Siegfried identified them as Micrografx Draw files based on the extension, but looking into the Hex showed that they are (IBM Lotus) Freelance Graphics Drawing files, which made more sense given the use of Lotus in the former computing environment.

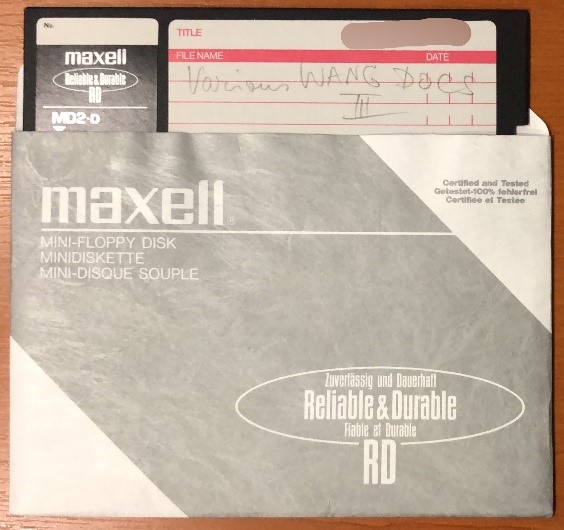

5.25" Floppy Disk "Various WANG DOCS III"

One open challenge that we would like to solve is how to open and migrate Wang Word Processing documents saved to a 5.25” floppy formatted as an “Archive Diskette” (see Chapter 8 of this Wang Word Processing Operator’s Guide). There are some Wang emulators out there, and even a Wang virtual disk format (.wvd). But it hasn’t been smooth sailing for us. We’ve tried getting the software to work in an emulator (which requires knowledge of rudimentary BASIC commands) so that we could then retrieve documents from the “Archive,” but we failed to get the software running. Richard Lehane came up with a nifty tool to read the contents of a Wang archive disk, but we have not yet been able to actually recover the documents. We know they’re there – we can see them in the Hex Editor. We have yet to break through the barrier of Wang formats. We hope that in the not-so-distant future, tools will be able to assist in identifying and reading Wang disks, but we also know we must contribute if we want to make this a reality.

Looking Ahead

We still have a lot of barriers to break down. Training more staff to use the preservation workbench and to know how to approach digital material on storage media is essential to break down barriers and engage in knowledge sharing. We also still have a lot of work to do to make preserved digital material more accessible to users. While we do not have a large-scale plan at present, there is a lot of potential to have users experience the value of preserved digital material. For all the format issues we’ve encountered, many formats still readable and can be (re)used in different ways from paper resources. We have Lotus 1-2-3 spreadsheet files that can be read and used in Libre Office Calc that up until now have only been available as bound print outs from a dot matrix printer. These Lotus 1-2-3 files allow users to interact with data that otherwise was quite literally flat. We hope by sharing our experiences both internally and with the wider community we can encourage others to take actions to breakdown preservation barriers.