Jaana Pinnick is Grants Manager and Research Data and Digital Preservation Manager at the British Geological Survey

A.K.A. a brief timeline of the digital preservation journey at British Geological Survey (BGS) and National Geoscience Data Centre (NGDC) over the last few years

Around this time in 2016, the initial thoughts I had had to explore digital continuity and preservation needs at BGS were starting to develop further. I had finished my MSc thesis on “Exploring digital preservation requirements: A case study from the National Geoscience Data Centre (NGDC)” which led to my first peer-reviewed article being published in the Records Management Journal. During my studies I had discovered that our parent body UKRI (then still RCUK) was a member of the DPC, so I approached Juan Bicarregui, Chair of the DPC who works at the Science & Technology Facilities Council (STFC) to ask if I could join. I soon got in the habit of attending DPC events, meeting William, Sarah, Paul and others, not forgetting other digital preservationists from around the world and learning a lot from them. Their jobs sounded fascinating so I took a Post-Graduate Diploma in Digital Preservation at the University of Aberystwyth with Sarah Higgins, and learned some more. But what next?

At BGS and NGDC we hold lots of research data, both digital and analogue. I had run a small stakeholder survey as part of my thesis research about the need to maintain the long-term accessibility and usability of our data. I started planning our work on a shoestring budget, talking to both research and data management staff, and it was clear that we needed a policy on how to deal with ‘aging’ digital data. Luckily, I had attended a DPC workshop on how to write a digital preservation policy, and after researching other organisations’ policies I wrote the first BGS DP policy.

At BGS and NGDC we hold lots of research data, both digital and analogue. I had run a small stakeholder survey as part of my thesis research about the need to maintain the long-term accessibility and usability of our data. I started planning our work on a shoestring budget, talking to both research and data management staff, and it was clear that we needed a policy on how to deal with ‘aging’ digital data. Luckily, I had attended a DPC workshop on how to write a digital preservation policy, and after researching other organisations’ policies I wrote the first BGS DP policy.

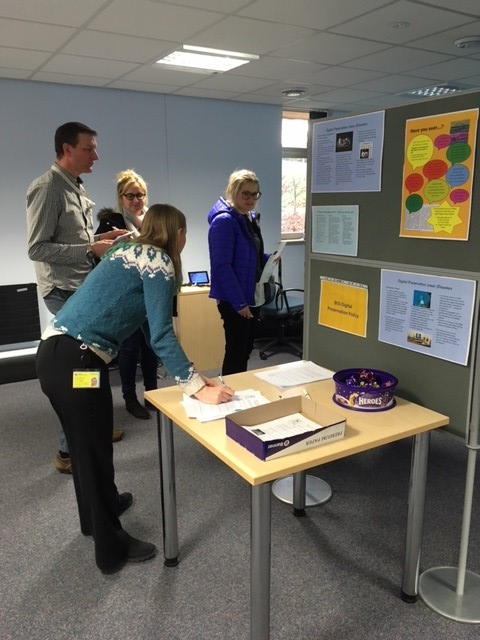

I was also rummaging in the BGS legacy media store containing ~5,000 pieces of various storage media, learning how to use DROID, talking to colleagues about their floppy disks, Lotus spreadsheets, Bentley MicroStation, emulation setups (yes, they are that clever!) and old LTO tapes. These gave me an idea to set up a pop-up computer museum at BGS on the first #IDPD2017. It turned out to be very popular with my older (in BGS age) colleagues who had worked with many of the gadgets presented to their colleagues. BGS data management staff started to get involved in the outreach work and we were having more ad hoc discussions about adding more preservation capability to our messages and procedures.

During the #WDPD2018 I delivered a taster digital preservation training session and a staff talk to showcase our new digital preservation strategy which was being developed. We also published our first Preferred File Formats list, and studied the PREMIS metadata schema with a view of developing a module to add to our discovery metadata schema.

During the #WDPD2018 I delivered a taster digital preservation training session and a staff talk to showcase our new digital preservation strategy which was being developed. We also published our first Preferred File Formats list, and studied the PREMIS metadata schema with a view of developing a module to add to our discovery metadata schema.

In 2019 we developed and ran a digital research data survey for BGS researchers to find out what was really happening on the grassroot level. The purpose was to inform our preservation programme development and to strengthen links between research data management (RDM) and digital preservation. We then published an internal report describing our findings and started doing a gap analysis between the researchers’ needs and the RDM service provision. To showcase how we were combining our geoscience RDM training course with preservation capability development, I gave a talk at iPres 2019 at the Eye Film Museum in Amsterdam. But 2019 was not over yet, and we completed the DPC RAM exercise and ran another WDPD event with posters, video clips produced with BGS graphics team, a quiz and games, cakes and cookies!

Just before the first lockdown in 2020 our data scientist Alex helped us by scanning terabytes of data on corporate shared drives to find out what we’ve got – as per the NDSA levels of digital preservation. The updated Library of Congress annual Recommended Formats Statement, for the first time including a category for GIS, geospatial and 3D data, was very informative and useful as we updated our Preferred Formats List. We were also exploring the technical side of creating checksums and running fixity checks in our ingestion workflow (thanks to Paul Wheatley for the information).

In 2021 we finally created a dedicated NGDC digital preservation team! Every team member has been at BGS for quite a while (15-20+ years) so they are well versed in geoscience data types as well as data management processes and workflows. We set out by getting the team members top-up training through TNA courses, setting them up with access to DPC website and training materials, and encouraging lively discussions about enhancing our preservation capability at our team meetings. This gave the team more confidence to integrate preservation thinking and activities within their existing workflows.

After the first six months of working together, I invited the team members to provide some feedback on our journey so far:

Sally: “Working in the data management area at BGS for over 20 years I have seen many changes in how data is captured. It has now become clear that digital data preservation is a key issue for the future of the data we hold. When Jaana asked me to join the newly formed Digital Preservation team I was very keen to get involved. I have spent the first few months reading articles and blogs, and undertaking the TNA/DPC training to give me the skills to help develop and implement digital preservation strategies and workflows, in particular to look at the ingestion, access, use and reuse of digital information and take active steps to preserve it for the future.”

Rob: “My work with “digital preservation” began at the start of my career 15 years ago, getting in on the ground floor with digital capture of analogue records, both for wider delivery to science and as disaster recovery. In doing so I embraced open, long-term reproduction standards so that no-one (myself included) would have to repeat the capture exercise again. I then moved to managing marine data, involving gradually migrating our data holdings to non-proprietary formats where possible. The team was small and the work varied, so it was important to make sure that I could pick up my own work again in the future, as there’s little more embarrassing than not understanding your own work. This meant things like embedding naming conventions into files and folder structures, and writing documentation that explains what is here, what was done and what is still to be done were important.

I expanded this experience out to the wider records collections, and collaborated on guidance on implementation of scanning standards, ingestion of other organisations’ data, and perhaps most importantly worked on getting data back out to scientists and public users. Helping users understand our data holdings means they can do innovative things with them, and there is a reciprocity in that they then understand how to organise and document their work for others to benefit from.”