Somaya Langley is Digital Preservation Manager at the Science Museum Group

If you’d asked me two decades ago what managing and preserving the memory sector’s digital and audiovisual collections would look like today, the picture I’d have painted would’ve been one where the metaphorical sky contained far more radiant shades.

Approximately two years ago I joined the UK’s Science Museum Group (SMG) as their inaugural Digital Preservation Manager. SMG consists of five museums across England (based in Bradford, London, Manchester, Shildon, and York) plus offsite stores for our collections, which very soon will all be located at our National Collections Centre. We also have archives and libraries across our sites. Two years on, I’m joined by my first staff member, Richard Moores, as SMG’s inaugural Digital Collections Specialist. We each bring wide-ranging skills and experiences in audiovisual and digital contexts from across the breadth of the arts, broadcast, culture, and live performance practices. Our collective experience working at the intersection of art, creativity, culture, performance, and technology positions us uncannily well to embrace the vast digital preservation and digital collecting challenges that lie ahead.

SMG doesn’t do things by halves. Our values – which can be found in our Inspiring Futures Strategic Priorities 2022-2030 – include ‘think big’. For example, our approach to sustainability includes an 88 acre solar farm hosted on SMG’s 545 acre Science and Innovation Park near Swindon, where our National Collections Centre is based.

There is already a considerable and very diverse range of digital and audiovisual content in SMG’s collection, as well as in our corporate records.

Figure 1: Set of 20 interviews on audio cassettes 'Pioneers of Computing'. 1976. CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0

Digital and audiovisual content held on both analogue and digital carriers incorporates tapes, records, film, CDs, cartridges, floppy disks and much more.

Figure 2: Film in metal canister entitled 'Satisfied Users'. CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0

The variety of carriers is impressive; the preservation challenge is definitely big. For instance, SMG holds more 8-inch floppies than I’ve encountered in any collecting institution. Carriers in SMG’s collection are acquired as physical objects. Other carriers have been collected as they contain unique digital or audiovisual content. In some cases, carriers have arrived alongside a collection object. For example, these tapes and disks were acquired with a Fairlight CMI synthesiser. These were donated to SMG by Robin Scott who found fame with his new wave band M that charted internationally with the track Pop Muzik.

Figure 3: Media containing samples for Fairlight CMI Series 3. CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0

Audiences that visit SMG’s museums in person can experience a range of interactive digital and audiovisual works found in both permanent gallery displays such as Who Am I?, and exhibitions including Science Fiction and Turn It Up (the latter contains Imogen Heap’s MiMU gloves). SMG has a decades-long history of providing inspiring experiences incorporating interactivity, digital, and audiovisual, which includes Christian Moeller’s Do Not Touch, and Mark Hansen and Ben Rubin’s Listening Post. In recent years, photography of objects in SMG’s collection can be accessed via our Collections Online and Never Been Seen.

Our digital collecting desires are equally expansive. Similar to other collecting institutions, the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic (and associated lockdowns) quickly drove the ramping up of digital collecting activities, including through SMG’s Rapid Response COVID Collecting. Around the same time, SMG’s National Science and Media Museum (NSMM) was involved in collecting a social media meme, as discussed in Arran Rees research.

Meanwhile SMG’s digital corporate records are the most varied I’ve encountered in a collecting institution. Our digital and audiovisual corporate records include complex digital objects, hybrid digital works, and interactives that have been created and commissioned for decades worth of exhibitions. They also also encompass our stories of science and innovation (such as the introduction to our Information Age gallery), right through to our learning programme games and apps, including our award-winning Wonderlab AR app.

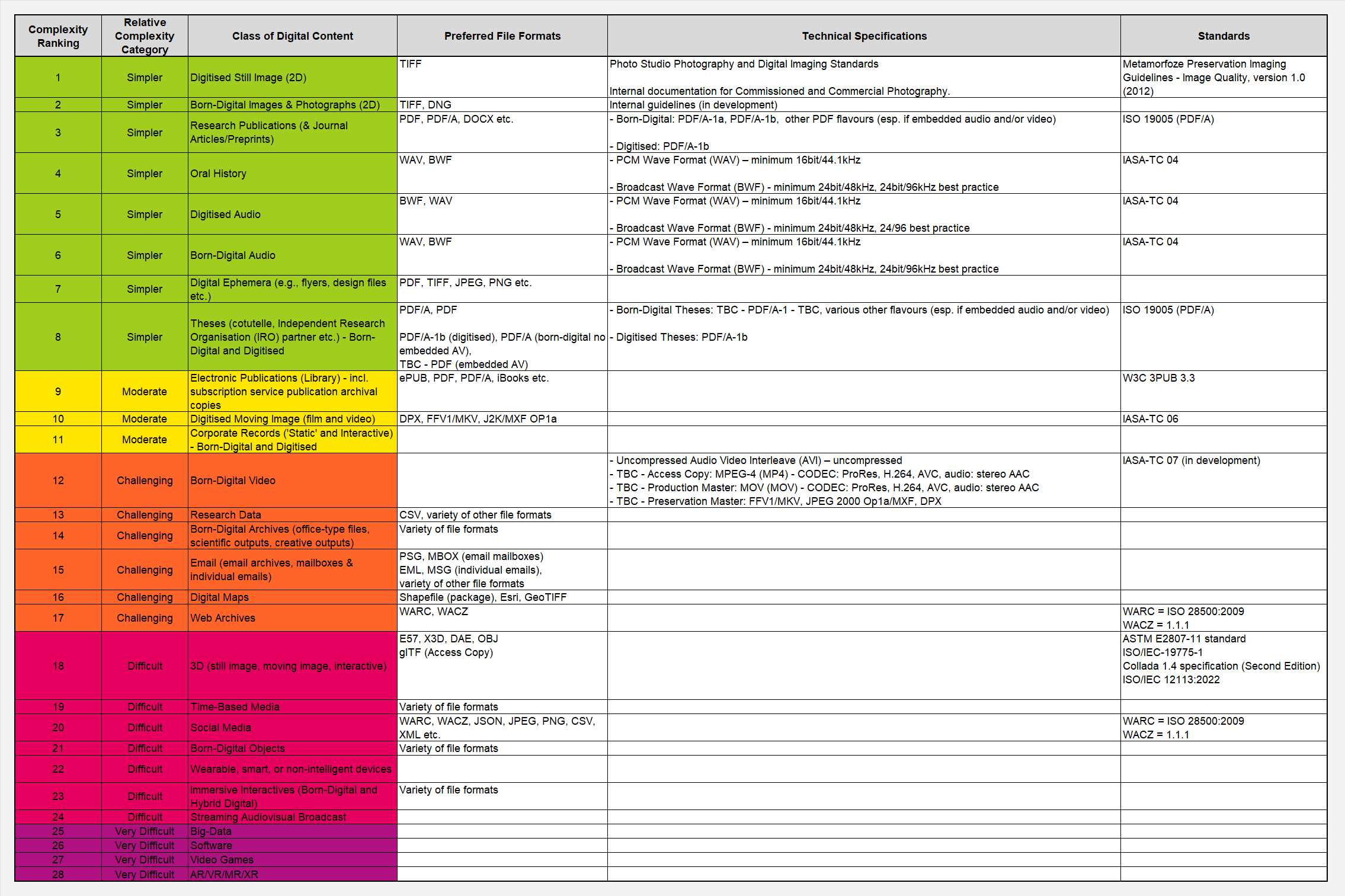

When it comes to acquiring digital content, the appetites of SMG’s dozens of curators and archivists is not abating. Yet we are only beginning our journey of collecting born-digital and hybrid-digital objects. To support these activities in their infancy, I have been iteratively developing a Digital Content Assessment Tool. I spoke about a component of this tool – the Digital Formats Complexity Scale – at the Museums Computer Group (MCG) Museums+Tech 2022 conference. Over the past year this tool has been developed further, however there is still more work to be done, particularly around technical specifications. (We will need to develop a range of guidance as there are few internationally agreed upon preservation standards available for a lot of the digital content we want to collect.)

The Digital Formats Complexity Scale provides SMG with an organisational-specific context, indicating categories of acquisitions that will be ‘simpler’, through to ‘very difficult’. Unsurprisingly, the latter is made up of many types of complex digital objects.

For figure 4 click here: Digital Formats Complexity Scale

As an internationally agreed-upon definition doesn’t exist for ‘Complex Digital Objects’, I authored the following for SMG:

An object, item, or work with a component that is digital, is made up of multiple files (likely of differing file formats) and may or may not incorporate a physical component. A Complex Digital Object is likely to depend on software, hardware, peripherals, and/or networked or non-networked data, platforms, and/or services.

In addition, as the definition of a ‘Simple Digital Object’ refers to a single digital file (and it’s derivatives), I also needed to define digital objects that are ‘simple’ but are made up of more than one file (plus derivatives). We are referring to these as ‘Simpler Digital Objects’.

The categorisation (and colour coding) of ‘increasing complexity’ in the Digital Formats Complexity Scale helps illustrate to curators and archivists venturing into the digital collecting space, what could be complicated to collect. It is also a mechanism to indicate that time and research and/or additional knowledge and resources may be required. Like the Library of Congress’ Sustainability Factors, categorisation is organised based on a set of factors. These include the availability of file format documentation, through to specialised knowledge of specific file formats within the international digital preservation community (including the Digital Preservation Coalition (DPC) members). As Wheatley (2022) wrote in a DPC blog post: “Considering [a] file format in isolation is therefore often unhelpful if not meaningless…”. Mitigating dependencies (software, hardware, peripherals etc.) is also a factor.

There is a desire to be presented with easy to comprehend ‘preferred file formats’. However it is imperative that SMG colleagues understand that internationally accepted guidelines and/or standards for much of the digital content we will be collecting may not exist. Technical specifications – and how parameters are configured to produce files that meet these technical specifications – is also critical.

The Digital Formats Complexity Scale is also contextualised, framed around the skillsets that colleagues from right across SMG already possess. As Wheatley (2022) also states in his same blog post “context is everything”. This tool will help us to plan training and development within the SMG context. For starters, we want to enable colleagues to Quality Control (QC) check born-digital and digitised content. The goal is also to connect SMG colleagues with the wider digital preservation community, so as to join us on our journey of acquiring and preserving digital collections. We know it will take a ‘concerted effort’ – drawing on knowledge from the international digital preservation community – in order to address the broad range of digital content we are planning to collect.

Figure 5: Film canister entitled: 'Working with a Computer'. CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0

With each new acquisition, it is my hope that SMG curators and archivists delve a little deeper and incrementally expand their understanding.

Like many museums around the world, there is a long road ahead to address the sustainability of our digital and audiovisual collections. My hope is that Richard and I can bed down fundamental principles, so that over time the Digital Formats Complexity Scale becomes ‘greener’ and less ‘purple’. I also hope our colleagues become increasingly comfortable with the common digital preservation response to their questions: “well, it depends”.