For the last couple of years, I’ve been an embedded PhD researcher in the Design and Digital curatorial section at the V&A Museum, London. During my time there, I’ve been lucky enough to work alongside colleagues across different departments, both when conducting my PhD research and working on additional projects. So in response to this year’s WDPD theme of concerted efforts, I want to celebrate the value of researcher-institution collaborations, and the power of working at intersections. Because as an AHRC-funded Collaborative Doctoral Researcher, collaboration is quite literally in the name. And as someone working on digital collections care, I continually operate at intersections: between the museum and academia; between curatorial and preservation concerns; and between theory and practice.

The V&A is a DPC member with a significant digital art and digital design collection. It holds the National Collection of Computer Art, having been acquiring computer art since the 1960s. Born-digital works also began entering the collection around the 2010s, and this now includes software-based art, videogames, archived websites, videos, an emoji and mobile apps amongst other things.

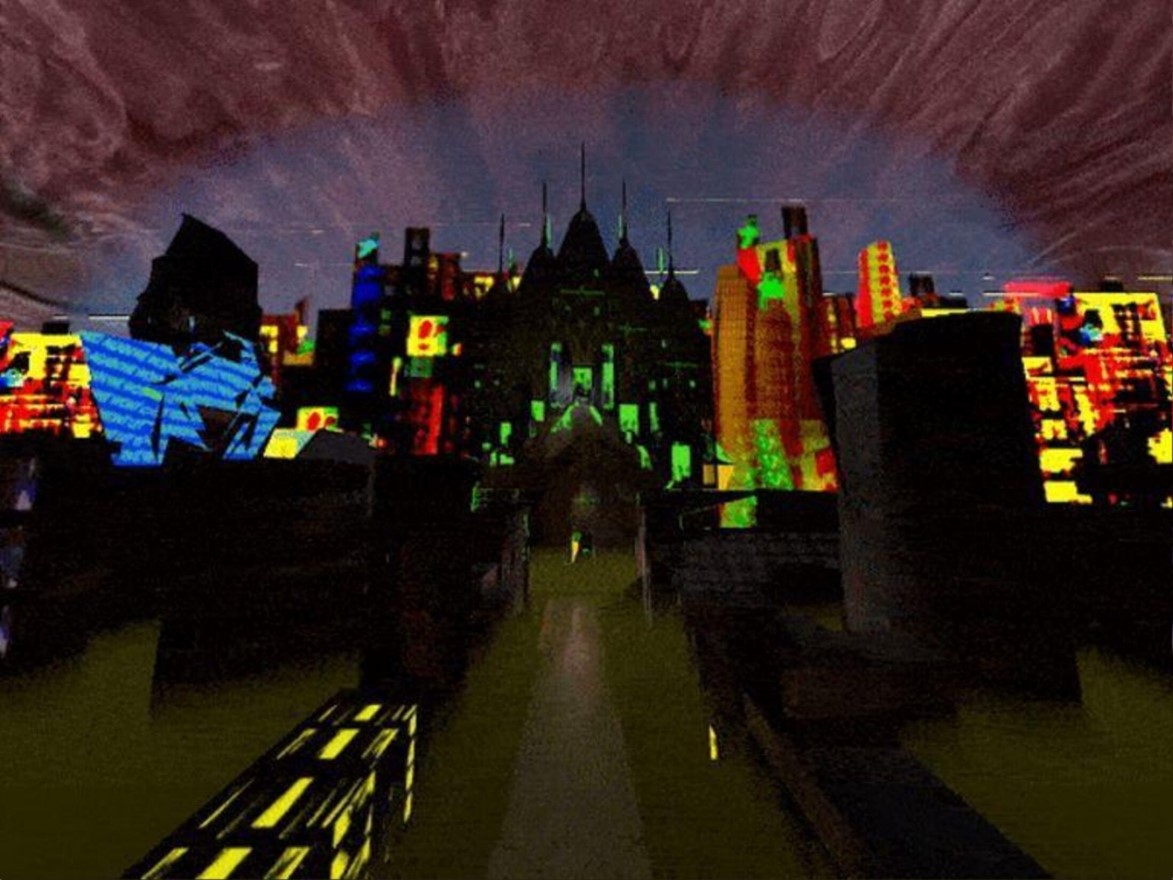

Blacktransair.com / I CANT REMEMBER A TIME I DIDNT NEED YOU, Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, 2020. Object number CD.3-2023 © Victoria and Albert Museum.

My research is concerned with this born-digital collection, but specifically the museum’s first software-based artworks, acquired around 2011, which I use to examine digital objects’ changing condition states in museum collections over time. Now around 10-15 years old, each work has presented differing non-critical malfunctions that have altered or prohibited my research access, which has centred questions of how/why digital objects break down in museums’ care. It’s also taken obsolescence and preservation concerns beyond the object alone. And whilst these objects await preservation, their ambiguous status (being both after malfunction and before restoration) establishes a speculative encounter with the no-longer and the not-yet. With this, I explore notions of stewardship, access and interpretation after failure.

As it might sound, this project is deliberately theoretical. And yet, these questions emerge from and feed into pressing challenges facing all memory institutions collecting complex digital objects: what to do with rapidly obsolescing things? How to interpret instability, variability and loss? What do rapid decay and non-performance mean for what we understand museum collections to be and do into the future?

Left: Ernest Edmonds’ Shaping Form 14/5/07. Object number E.294-2011 © Victoria and Albert Museum.

Right: Random International’s Study for a Mirror. Object number E.295-2011 © Victoria and Albert Museum.

During my time in the museum, I completed a research project studying the care history of the V&A’s first born-digital collections, which was commissioned at a critical point of preservation for these early works, and in anticipation of incoming complex acquisitions. Building on conversations with colleagues across the museum, the project involved assessing the objects’ conditions against their past acquisition procedures, histories of display, storage and care interventions.

The goal here was longer-range insights into how complex digital objects are best sustained in museum collections. But for me, the research also evidenced the always-collaborative nature of digital collections care. It surfaced the latent informal stewardship networks that were instrumental for digital collecting, and demonstrated the significance of individuals’ deep personal commitment to care.

The process of first bringing digital objects into the museum was both measured and reactive, conducted without formal collecting procedures or dedicated resourcing. Official job remits were adapted by key individuals acting in lieu of digital conservators, and specialist knowledge was learned along the way. Digital objects continually demand new skillsets and new organisational approaches, but they also blur established categorical distinctions such as equipment maintenance and object conservation. Whilst the research findings exceed a short blog, it’s safe to say that the success of this early digital stewardship period lies in the works’ presence in the museum today – both for their art historical value, and for the preservation insights that we otherwise wouldn’t have.

Being in a research role means I have the time and space for this work which can otherwise be difficult to achieve. But this is necessary work, and the project culminated in an internal report with evidence-based recommendations to support the museum’s digital collections capabilities. This report and its accompanying condition spreadsheet was not the V&A’s first research into digital collections care, nor is it the last. It has since underpinned additional projects, including an artist’ questionnaire just developed by a research colleague. Because, like daily collections care, research is always concerted. Each project is strengthened by past knowledge and each provides a foundation for future work. For me, this has been one small part of a much larger involvement in the museum community. But it has been a vital one, reminding me that what’s needed here is the active preservation of knowledge, skills, and social networks of relations, both inside and outside the museum.

For me, embedded research repositions academic study from that of individual enterprise to being part of a social network of care that transcends discrete projects and individual efforts, as much as curatorial-conservation and theory-practice distinctions. Because the task of digital preservation is always ongoing, and is only ever achieved with multiple voices, multiple approaches and multiple hands.