Matthew Addis is Chief Technology Officer for Arkivum

This blog post is both a demonstration of how to extensively torture a metaphor if you try hard enough, which I'm certainly want to do from time to time, and a look at some of the serious issues of digital preservation at an industrial scale outside of memory institutions.

The metaphor is washing machines, the industrial application is research data preservation, and the answer, perhaps paradoxically, is to choose to do less for more.

I've been involved for over 2 years now with the Jisc Research Data Shared Service (RDSS). This has the ambitious and laudable goal of providing a national Shared Service for Research Data Management to Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) in the UK, including the deposit, storage, publication and preservation of a wide range of digital research outputs.

I've been involved for over 2 years now with the Jisc Research Data Shared Service (RDSS). This has the ambitious and laudable goal of providing a national Shared Service for Research Data Management to Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) in the UK, including the deposit, storage, publication and preservation of a wide range of digital research outputs.

Just to give some scale to the problem, research in the UK by HEIs is funded to the tune of £6Bn per year, which supports some 91,000 researchers and academics across 220 institutions who produce a vast amount and variety of data that totals the thick end of 500PB. However, only 1-2% of that budget currently goes into long-term curation, preservation and access to this data. Even when including high-impact national and international services for research data such as the EBI or the UKDS, custodians of research data are outnumbered 500:1 by those who create the data in the first place.

If there's no national facility available, the responsibility for safeguarding and making research data available to the community often falls to a small team of just one or two people in an institution, often in the library. Here the story of digital preservation is a familiar one. There's not enough staff, they don't have the right skills, they struggle with the business cases for preservation, they find it difficult to engage researchers in the preservation process, and they don't have the budget to build the capacity to deal with research data at scale.

Doom and gloom? Not so! This is exactly the problem that Jisc are trying to address. The RDSS is a one stop shop for preservation and access, it's fully hosted, it's automated, it's scalable, and, perhaps most importantly, it brings HEIs in the UK together to help establish common practices and use of common infrastructure. I'm part of the Arkivum team on the Jisc RDSS project and we're working with Artefactual to deliver workflows and an open-source solution to HEIs for large-scale research data preservation.

Or as one the HEIs using the RDSS put it:

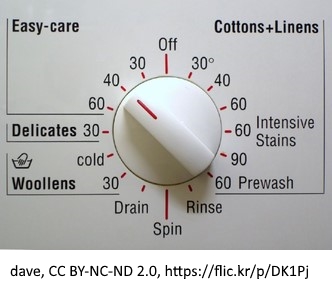

"What we want is a digital preservation washing machine". "We're looking for a fully automated wash cycle, with automatic dosing, and the ability for the machine to detect and apply the right programme (from delicates to denim)".

"What we want is a digital preservation washing machine". "We're looking for a fully automated wash cycle, with automatic dosing, and the ability for the machine to detect and apply the right programme (from delicates to denim)".

And if institutions want washing machines, then what Jisc is building is a digital preservation Launderette.

A place where HEIs can go to get their data clean, fresh and ready to wear again in the future. And just like a laundrette, the washing machines are industrial scale, they're automatic, and they are run as a service. No more DIY plumbing in the Library or growing piles of dirty data because the preservation repair man hasn't turned up!

But to think of this as about lowering costs, automating technology, and saving labour - all of which are important of course - is perhaps to miss the point.

The Launderette is also a place where people come together to discuss which wash cycles to use (policies), what washing powder works best (technologies), what clothes can go in together (data types), and how to get the most washing done (processes). The supply side then evolves to match - the drums get bigger, the machines have the wash cycles that people really need, and the washing powders work at lower temperatures and for more types of clothes.

And in that analogy lies the key is to industrial scale preservation of research data. The 30 degree wash with non-bio powder. A preservation cycle where you can throw in the vast majority of data into the drum, no matter what it is, and know that it'll come out that bit cleaner the other side - without shrinking, without colours fading, without threads being pulled or bits going missing!

The digital preservation community rightly spends a lot of time on how to do the best preservation job possible, including for increasingly complex and esoteric types of content, and using ever more complicated preservation systems and workflows to do it. This pioneering advances the digital preservation frontiers and necessarily so. But the great work of the pioneers should not become the enemy of the good settlers that follow. We need to do more to help organisations get the bulk of their data under some form of basic preservation control even if it's just the bare minimum needed - MVP (Minimum Viable Preservation) if you like, otherwise know as Parsimonious Preservation.

This is what I meant at the start of this post when I said do less with more. The least amount of preservation necessary applied to the most amount of data. Minimal preservation in order to get more done.

It's the 80/20 rule. 80% of research data could be handled with 20% of the budget - but only if we target it at scale and make sure the basics get done first. This reminds me of the PrestoSpace and PrestoPRIME projects that I worked on before Arkivum. PrestoSpace tackled the need for factory scale digitisation for the world's 100M hours of AV content. The findings were clear. Automated digitisation factories halve the costs. Factories need efficient workflows - just 10% of the time dealing with 'exceptions' increases the costs by 20%. And you need to start with the easy stuff first - if you spend all your time and money upfront on the 'problematic' content, or you delay action, then by the time you come back to the 'easy' stuff you find that's decayed and is problematic too - and your costs go up 5x overall. The same is surely true for research data. Get the bulk of it under control with simple and efficient workflows and then worry about the 'hard' stuff like esoteric formats afterwards, not first.

But to do this for research data we need the HEI community to define the equivalent of the 30 degree preservation wash.

It'll likely be a simple combination of establishing fixity for files, identifying file formats (where possible), adding minimal descriptive metadata (e.g. as used by DataCite), and then packaging for safe storage and access. This needs to be a quick, automated and non-invasive process that does 'no harm' to the original data, but does give a better chance of finding, understanding and using that data in the future. It's the bottom rungs of preservation maturity, e.g. the NDSA preservation levels or the DPCMM. But far better to be on the ladder at the bottom and see it as a great place to be than not to be on the ladder at all. For research data, that's a FAIR place to start.

It'll likely be a simple combination of establishing fixity for files, identifying file formats (where possible), adding minimal descriptive metadata (e.g. as used by DataCite), and then packaging for safe storage and access. This needs to be a quick, automated and non-invasive process that does 'no harm' to the original data, but does give a better chance of finding, understanding and using that data in the future. It's the bottom rungs of preservation maturity, e.g. the NDSA preservation levels or the DPCMM. But far better to be on the ladder at the bottom and see it as a great place to be than not to be on the ladder at all. For research data, that's a FAIR place to start.

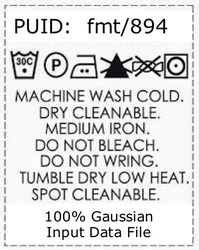

And it needs to be a safe bet for data that doesn't have a care label. Less than 40% of research data formats can be identified using PRONOM and even when a file format is identified it will often be a container (zip, tar etc.) or a generic structure (XML, CSV, txt etc.) which doesn't tell you much about the contents. Sending everything off to specialist preservation dry cleaners just because it might need special treatment isn't an option either! This is why a default 30 degree wash is so important. Anything and everything can and should go through it. If the results aren't good enough then you can always wash it again on a more specialist programme (or give it the boil wash!)

Many of the more advanced preservation washing cycles and powders are already available in today's preservation solutions, but the thing that's missing is a shared understanding of what the cycles do and when to use them. I'd argue what's needed here is a community registry of shared practice. Starting with the 30 degree wash. A bit like a public notice board on the Launderette wall that everyone can use to say what worked for them, including how to deal with "delicates as well as denim". We have registries for file formats, e.g. PRONOM, we have ways of finding tools, e.g. COPTR, and we have resources that describe how to do preservation in general terms such as the DPC handbook - but we have yet to establish registries that pull this together in a form that preservation systems can consume and practitioners can use to document and share real-world practice. I'd love to see the community, vendors included, coming together and working on this problem. It would help define a set of washing cycles that everyone understands and shares. It's about defining the standardised dial on the washing machine and the set of symbols on the care label.

A set of wash cycles isn't going to solve all the problems of research data preservation. Far from it. Preserving research data is just one part of dealing with Research Objects, which includes tackling the issues of the software sustainability. The question of how to preserve, access and re-use an interlinked and distributed combination of data, metadata, provenance, processes, software and services needs to be properly addressed if we want to make full use of research data in the future. But that's very much frontier work at the moment - the next generation of washing machine technology and beyond.

In the meantime, we need to focus on establishing a simple and fully-automatic 30 degree cycle backed by big community launderettes. This is key to achieving digital preservation at an industrial scale that's desperately needed for much of today's research data. This is where the Arkivum/Artefactual team is focussing our efforts in the RDSS project at the moment. Only in this way will preservation become achievable and affordable for the mass of research data our HEIs generate within the limits of the budgets and staff available. Or to put it more strongly, if we don't take this approach now then a very large amount of research data will never get preserved at all.