Three and a half inch floppy disk

When I first started out swimming in the deep waters of digital preservation and trying to understand what the risks were I lived with the fear that format obsolescence was our number one enemy and that we would need to spend all our time migrating content and upgrading and or else we would never be able to open those old Word Perfect files. However even then there were wise words from the likes of David Rosenthal who as long ago as 2007 and he predicted not a cliff edge crash of format types that would remain beyond our reach but a slow drift which (hopefully) with increasingly sophisticated emulation (and migration) techniques we can keep abreast of. My first steps in dealing with some of our legacy digital collections (all the way back from the 1990s) were imaging and capturing the contents of the floppy disks belonging to the distinguished historian Eric Hobsbawm which I wrote a bit about here.

I had expected disks and disks of unreadable text (mojibake or 文字化け ) but every single one of the Eric Hobsbawm floppy disks proved readable and accessible with Office Libre. I can say I was *almost* disappointed having read and admired Jenny Mitcham’s painstaking work on trying to access WordStar files from the Marks and Gram archive at the University of York. But after presenting my work on Hobsbawm’s disk to a group of practitioners and academics I learnt that there was a “tipping” point during the 1990s before which date word processing packages tend to be hard to access and open with modern software packages and after which things become much easier because of developing ideas about backward compatibility and interoperability. This isn’t something I know much about and although the majority of the digital material held at the Modern Records Centre dates from the very late 1990s onwards there is some earlier material and the more I know about the environment in which they were created I think the better I would feel I was equipped to deal with them.

However there is a different barrier preventing me from accessing the earliest digital content which not relating to the software but it’s more about things like this:

Five and a quarter inch floppy disk

Which I do remember

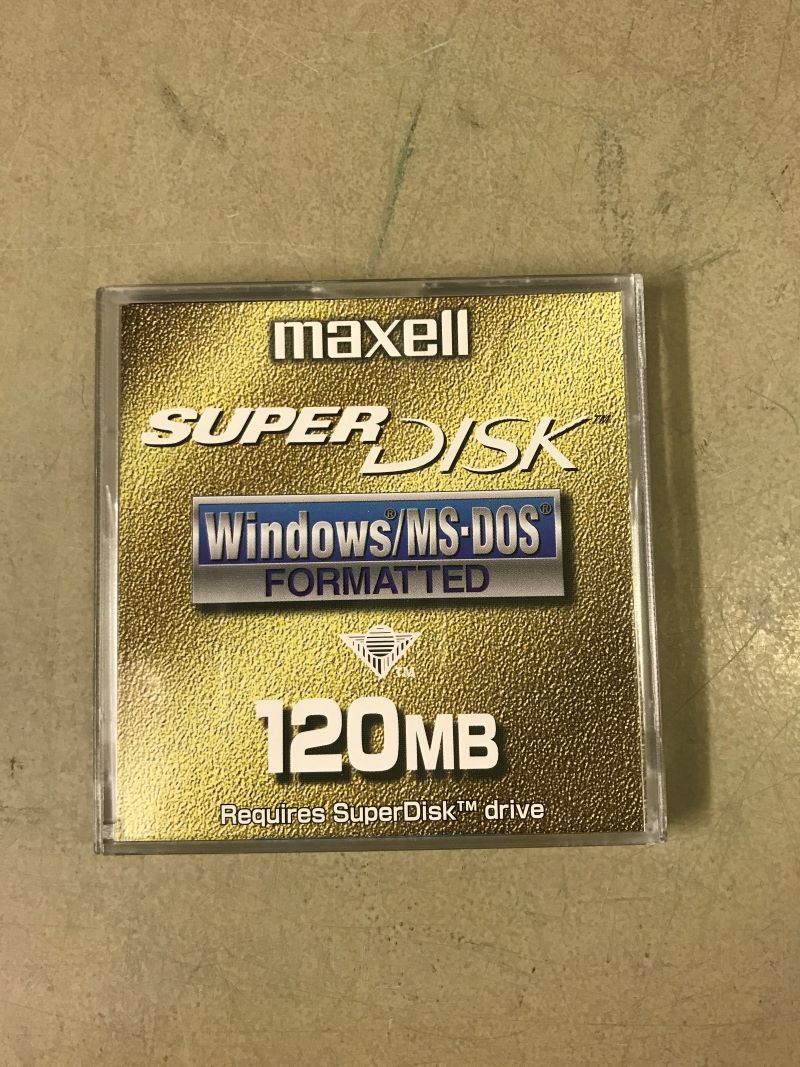

And this:

Super disk - old format

Which I definitely don’t!

I don’t have a 5.25” disk drive nor a Super Disk reader so I think in all probability they will stay where they are. The fact is that the amount of time and effort needed to track down the right kind of hardware, get it working and then grapple with sourcing the software and hoping the files are readable. The truth is – as with all kinds of archival work – a balance has to be drawn about how much time and effort to invest in a project. And in these cases there is nothing to suggest that the material that is probably stored on these disks is anything we would want to keep anyway. It just isn’t worth our while trying (although if anyone does have a handy 5.25” disk drive then please let me know!)

Anyway the files which were way older than the students who attend this University (!) seemed to generally be in good shape. Funnily enough it’s the more recent stuff we sometimes have to worry about. Nestling amongst the relatively recently acquired Warwick University 50th anniversary (2015) materials were a few internet shortcuts saved amongst the Word documents and pdfs. This is what happens when people want to save entire web pages but don’t have the necessary tools to do so. And of these links:

- Works and resolves to an internal site

- Does not resolve but I (eventually) tracked it down the UK web archive at the British Library – but you have to go there to view it

- A Storify link …

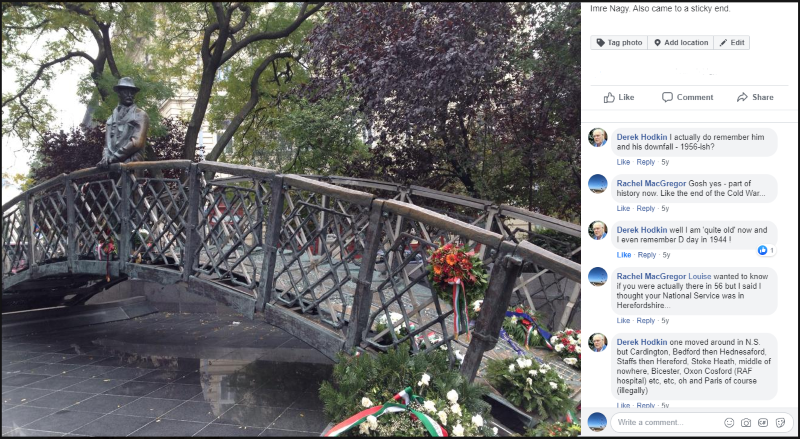

So that last one was a service which ceased to be provided in 2018 – ironically not that long before I got around to processing the material. In this case not really that big a deal but it’s in these online platforms – social media, blogs, corporate website, and institutional websites – that we see some of the clearest dangers. I am aware that my own personal interactions take place on Facebook are extremely- here’s a very typical interchange between me and my uncle who has very recently passed away. I have no idea how to rescue this from Facebook (beyond a screenshot) – it’s not even mine anyway. Our digital lives are very fragile and whilst cloud based systems offer flexibility and almost limitless storage they also offer the appearance of ownership which is at best a space which is rented and at worst borrowed with an onerous cost in terms of our data being mined for someone else’s benefit.

Screenshot from Facebook showing comments from my uncle

So remember – that website, those images which are “on the web” “in my blog” – they are only ever temporary unless there has been an active intervention to secure them.

Comments