Blog

Unless otherwise stated, content is shared under CC-BY-NC Licence

Another Recap of Aye Preserve

Gemma Batson is a Program Manager for Web Archiving at the Internet Archive. This post recaps her experience at 'Aye Preserve - Digital Preservation in the West of Scotland' on 30 November 2017 at the University of Glasgow.

It was a beautiful St. Andrew’s Day morning as we all made our way to the University of Glasgow for the Aye Preserve event, run by the Digital Preservation Coalition (DPC). As nervous students prepared for graduation on the main campus, our digital preservation colleagues descended on the campus library to begin discussions about our industry, how to get started, and the projects at the forefront of digital preservation in West Scotland.

Recap of Aye Preserve

Hania Smerecka is an archivist at Lloyds Banking Group. This post recaps her experience at 'Aye Preserve - Digital Preservation in the West of Scotland' on 30 November 2017 at the University of Glasgow.

On Thursday I had the pleasure of attending the Aye Preserve event held at the University of Glasgow. The event was perfectly timed to coincide with the International Day of Digital Preservation, and featured presentations from a number of speakers followed by the launch of the Digital Preservation Coalition BitList, a list of the world’s endangered digital species.

Here comes the sun: IDPD17+1

The sun has set now on International Digital Preservation Day (IDPD17) around the world, so, at the very last tick of the clocks on the most westerly reaches of the setting sun, we’d like to conclude by offering our thanks to colleagues in all time zones.

We have been astonished, delighted and massively energized by the numbers that participated, by the number of blogs, tweets, emails, messages on every media platform imaginable. There has been a significant effort of disk-imaging, file-migrating, and archive-describing. I never knew that ‘digital preservation cake’ was a thing but there’s been an awful lot of it in show; I didn’t know that a working ‘day’ could last for 39 hours; and I could scarcely have imagined the word ‘cryo-flux-a-thon’. There has been enthusiasm and generosity, insight and commitment, and a wonderful sense of celebration at the gathering of our dynamic, diverse and dispersed community.

I think it is safe to say that our first International Digital Preservation Day has been a success.

Preservation and Archiving Special Interest Group in Mexico City, 2019

Natalie Baur is Preservation Librarian at Biblioteca Daniel Cosío Villegas, El Colegio de México in Mexico City.

The Biblioteca Daniel Cosío Villegas at the Colegio de México in Mexico City is thrilled to announce that we will be the hosts for the next Preservation and Archiving Special Interest Group meeting! This exciting conference will be held at the Colegio de México’s installations from February 12-14, 2019, so save the date now! You will not want to miss this unique opportunity to talk digital preservation with colleagues from around the world. PASIG 2019 will be unique in that this is the very first time that the meeting will be held in a Latin American country. Mexico City is a vibrant, cosmopolitan city that will afford lots of excellent discussion on digital preservation advances locally in Mexico and throughout the Caribbean and Latin American region. We plan to have many attendees from across the region present at the meeting and this new infusion of perspectives and experiences will undoubtedly reinvigorate discussions happening in the international digital preservation community.

Creating a Linked Data version of PREMIS

Evelyn McLellan is President of Artefactual Systems and member of the PREMIS Editorial Committee.

It has been a busy couple of years for the PREMIS Editorial Committee. Since June 2015, when we released version 3.0 of the PREMIS Data Dictionary, we have been revising and releasing supporting documentation such as revised Guidelines for using PREMIS with METS and Understanding PREMIS, and updating and enhancing the preservation vocabularies, particularly the eventType vocabulary.

Perhaps the biggest undertaking, however, has been the preparation of a new OWL ontology by a working group that includes some members of the Editorial Committee plus external Linked Data experts and preservation practitioners. This is a work in progress and we are hoping to release a draft soon for a period of public review and feedback.

Losing the Battle to Archive the Web

David S. H. Rosenthal is a retired Chief Scientist for the LOCKSS Program at Stanford Libraries.

Nearly one-third of a trillion Web pages at the Internet Archive is impressive, but in 2014 I reviewed the research into how much of the Web was then being collected and concluded:

Somewhat less than half ... Unfortunately, there are a number of reasons why this simplistic assessment is wildly optimistic.

Costa et al ran surveys in 2010 and 2014 and concluded in 2016:

during the last years there was a significant growth in initiatives and countries hosting these initiatives, volume of data and number of contents preserved. While this indicates that the web archiving community is dedicating a growing effort on preserving digital information, other results presented throughout the paper raise concerns such as the small amount of archived data in comparison with the amount of data that is being published online.

Digitization Is Not Digital Preservation

Peter Zhou is Director and Assistant University Librarian at University of California, Berkeley

Over the past decade, I have spoken frequently at conferences on both sides of the Pacific, on digital information management and digital preservation, and I have just as frequently encountered academic leaders, librarians, and information specialists working under the misconception that digitization somehow equals digital preservation.

To many, converting print or analog content to a digital format and transferring the converted content to a disk, server, or other storage devices is an exercise in digital preservation. I usually point out that digital conversion makes content digital, but it cannot and will not guarantee that the digitized content can or will be preserved for an unspecified period to come, since the new format may become old, obsolete, or unusable in a matter of a few years—and then there are the problems of format reconciliation, checksum, error correction, data storage, and data migration, all of which are critical components of a robust digital preservation operation, whereas by simply storing the digital content and doing nothing else, one will miss all those vital steps.

Digital Preservation 2007-2017

Art Pasquinelli is LOCKSS Partnerships Manager at Stanford University Libraries in Palo Alto, California USA

I wanted to take the opportunity of the International Digital Preservation Day to do a retrospective on how we have evolved with regards to Preservation and permanent access over the last decade. So, I looked at two agenda snapshots; one from one of the earliest Preservation and Archiving Special Interest Group's (PASIG) meetings in May 2008 and the other the latest meeting in Oxford in September 2017. The initial meeting can be seen at http://www.preservationandarchivingsig.org/index.html and the latest one can be viewed at https://pasig.figshare.com/pasigoxford. After looking at the content of the two Preservation meetings I came away with a very positive impression. Here are a few reasons why I feel so upbeat.

It’s difficult to solve a problem if you don’t know what’s wrong

Shira Peltzman is Digital Archivist for the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Library Special Collections

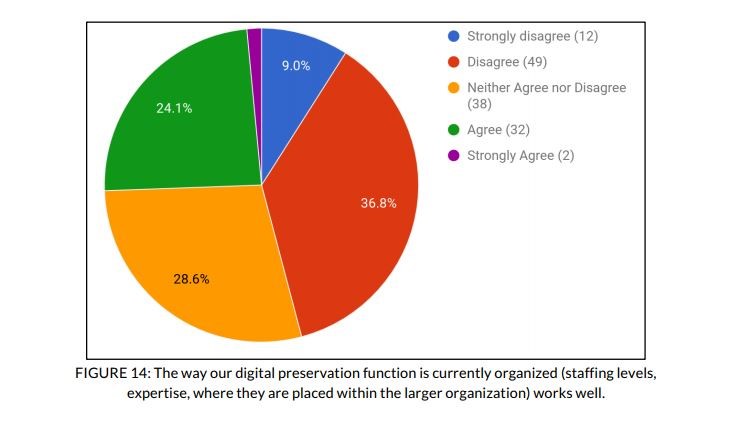

Buried in the recently published findings from the 2017 NDSA Staffing Survey is evidence of a growing discontent among practitioners with regard to their organization’s approach to digital preservation. The survey asks respondents whether or not they agreed with the following statement: “The way our digital preservation function is currently organized (staffing levels, expertise, where they are placed within the larger organization) works well.” Of the 133 people who took the survey, 61 of them, or roughly 46%, either disagreed or strongly disagreed with that statement.

“Q16 - The way our digital preservation function is currently organized (staffing levels, expertise, where they are placed within the larger organization) works well. [133 respondents]”] Taken from “Staffing for Effective Digital Preservation 2017 An NDSA Report”: http://ndsa.org/documents/Report_2017DigitalPreservationStaffingSurvey.pdf

To say that those numbers aren’t great would be an understatement. To make matters even worse, they represent an increase from the 2012 iteration of the survey, in which 34% of participants reported that they were unsatisfied with how things were organized.

Lossy Accelerant: Surfeit and Fragment in Digital Collections Archives

Jefferson Bailey is Director of Web Archiving Programs for The Internet Archive in the USA

Archival collections have always been incomplete. Being homogenous, selective groups of records preserved through time, they support attestation and evidentiary consideration only through their longitudinal availability. Multiple appraisal, selection, and processing strategies have developed over the history of the archival endeavor to address the ways in which the archival collection is, by nature, a partial or symbolic representation. From documentation strategy to the study of “archival silences,” both archivists and users alike have grappled with the challenges of incompleteness inherent in the archive. The emergence of born-digital records, and the ease of their creation, alteration, and publication, has compounded these challenges by introducing a documentary environment that is at once more rich and more easily preserved, but also more dynamic, more ephemeral, and more partial. Furthermore, digital records have introduced their own characteristics of incompleteness: bit corruption, format migration, rendering and technological dependence, and other vulnerabilities that can impede recreation or interpretation.